Robert's New Year Resolutions

What I'm changing, and what I'm aiming for in 2023

New Year's resolutions are a terrible idea. Statistics vary as to what percent of New Years’ resolutions fail, but the average appears to be around 80% of them. The problem with these is that they are usually broad, vague, beyond our abilities, unrealistic, or on too long of a time scale — or all of the above. It would be much better to set goals instead, especially ones that are specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and time-bound (“SMART”).

But I still make New Year’s resolutions — and I don’t apologize for it. Because while here at Grading for Growth we are all about clearly defined standards, there’s also a lot to be said in favor of big, possibly unrealistic, definitely aspirational goals that have only a hint of specificity to them to set the tone for the year. This can be a smart thing to do even if the resolutions are only partially “SMART”. And, it’s fun.

Here are three alt-grading resolutions of my own for this year.

Simplify

Resolved: To make specifications grading in this year’s courses simpler than it was in last year’s.

I know, this was also David’s top resolution and I swear I didn’t steal it from him1.

My first foray into specs grading in 2017 was spectacularly overcomplicated. That class had 68 learning objectives, each of which required both an assessment and a reassessment. And that was just the beginning of the opacity and unwieldiness of that class. I've been on a quest for radical simplicity ever since.

How do you know when you’ve successfully simplified one of your courses? There’s no single agreed-upon metric for this, but I have a theory: Look at your syllabus process for assigning a course grade. If a student is likely to take one look at your syllabus process and feel like they are in over their heads, then it’s highly possible that the entire grading system is still too complicated (and anyway, it’s hard to overcome a bad first impression). On the other hand, if in all honesty you believe a student would look at the syllabus process, and even after knowing what all the parts signify the student would not feel completely terrified and lost, then you’re likely on the right track in terms of simplicity.

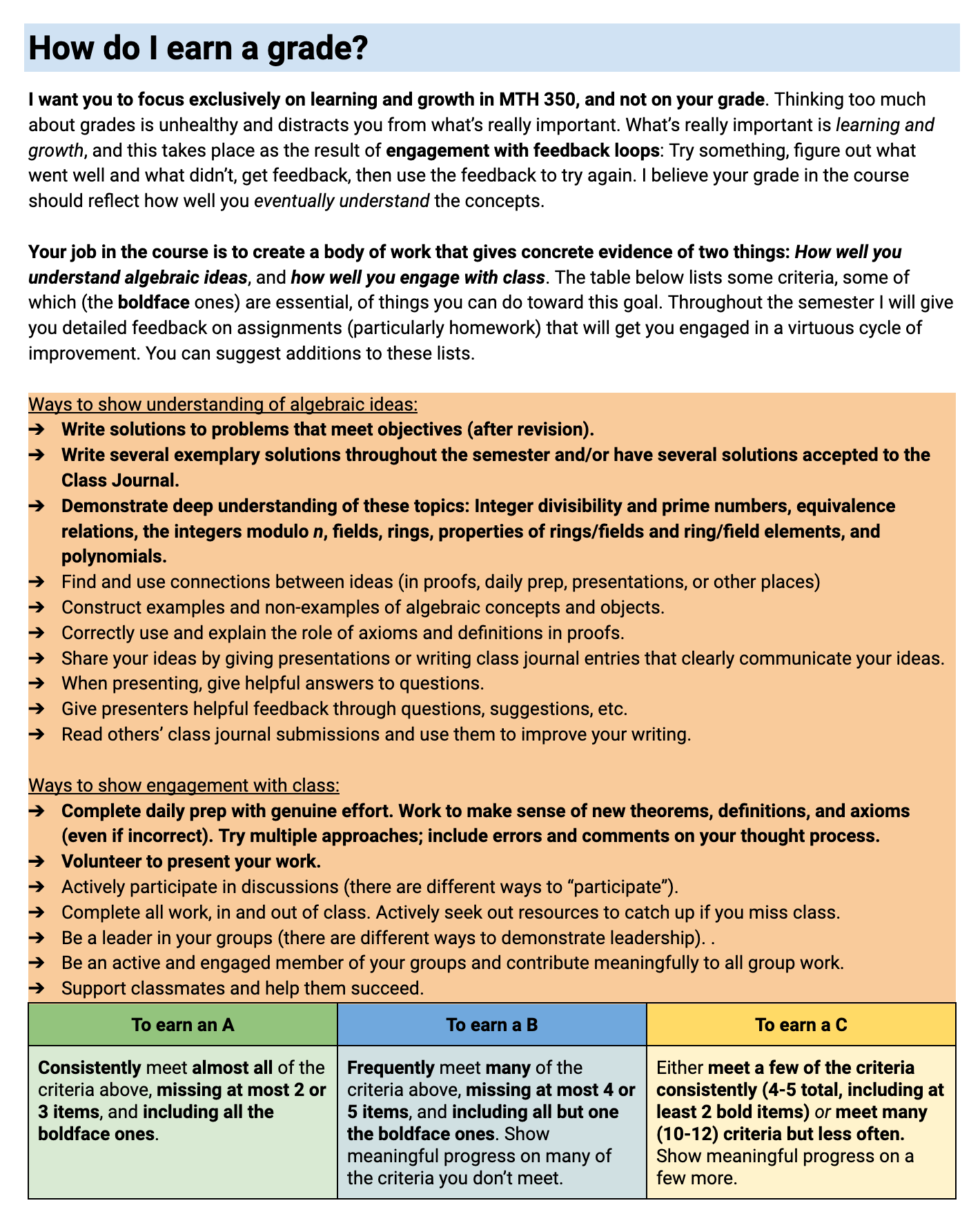

In the spirit of transparency, here’s what this looks like starting with Winter 2022 (this time last year). This was my first and so far only experience with ungrading, and this is the relevant part of the syllabus (an entire page):

I offer this without further explanation because that’s the point: The feeling — on a spectrum from paralysis with fear, to “I got this” confidence — is a proxy for the simplicity of the grading system. If it needs to be explained in detail, then it probably needs to be simplified some more.

I went back to specifications grading in Summer 2022 and had this in the syllabus:

To me, this definitely seems simpler than the previous course. Although there are some details hidden (what’s a “badge” and what does it mean to “earn” one?) there are definitely fewer moving parts, which I think is the essence of simplicity. In a grading system, I think it means getting the richest and most valid data about student learning and growth, out of the smallest number of assessments. Think “bicycle” instead of “automobile”. Then think “single-gear bike” instead of “21-speed bike”.

So moving forward, thinking about this resolution, I am trying to minimize the number of components to the grading system while improving the signal-to-noise ratio of each one. I am interrogating every element of my courses and if there are learning objectives or assessments that aren’t absolutely essential, they’re gone, or transformed into something with a smaller footprint.

Here’s what I have for this semester’s course:

Hmm… I don’t know if this is simpler or not. But I do know that the checklist version of this is pretty easy on the eyes:

But I could be letting my nerd flag fly at this point.

Provide training and practice

Resolved: Devote significant time at the beginning of the semester for explicit hands-on training with students on how to use the grading system.

I know I just said that if the grading system needs extensive explanation, it’s not simple enough. But it’s still a good idea to make sure students know how to use the grading system and aren’t merely comfortable looking at it. Over the years since I started using specs grading, I’ve learned that this requires explicit training; and that requires dedicated time.

When I started my sabbatical at Steelcase in 2017, I went through what is called “onboarding”. This term refers to experiences for new employees to get them acclimated to the culture and processes of their workplace — to get them “on board”. In my case, I met people from the org chart including the CEO; learned their product line (Verb, Node, Thread, etc.); discussed the values and mission of the company; and so on. It occurred to me lately that college classes need an onboarding process too. So I’ve decided to give mine one.

My class this semester (two sections of a Linear Algebra and Differential Equations course for engineers) meets two hours every Tuesday and Thursday, starting this past week. Rather than cover content:

During the first meeting, I had students get into groups and then asked them two questions: What is something you’re good at doing? and How did you become good at it? They share with their group-mates, and it’s a good way to get to know someone. But it also causes them to reflect on how humans learn things. One hundred percent of the time I have done this activity in the past, students isolate all the right things: Practice. Play. Time. Failure. Multiple attempts. Having other people help you. And I have never had a student say that they got to be good at their “thing” through lectures or other passive experiences, or by getting a grade on something. From that point forward, the concept of specifications grading needs almost no explanation. I also have students go through Dana Ernst’s Setting the Stage activity. After day 1, students have come to understand what sort of learning environment they are in, how they will succeed, and what we value.

During the second meeting, I set aside 30 minutes to go through some synchronous training on using the grading system in the syllabus. They get two hypothetical end-of-semester scenarios of students with a set of accomplishments, and they’re asked whether the student has earned an A, B, C, D, or F in the course.

Later, they do more of these what-grade-did-they-get questions on a quiz on our LMS that they complete as part of a Startup Assignment.

Something David wrote in the Grading For Growth book, and he’s written it here too, really resonated with me: That if you are going to assess something in the course, you have to actually teach it and not just assume students spontaneously come to know it somehow (or knew it already). I’ve decided that the grading system itself is like that — I want students to be fluent with it, and so it’s on me to actively teach it. The goal being that we focus in on how grades work in week 1… and then as much as possible, forget about grades altogether until the end of the course.

Show more empathy

Resolved: Intentionally practice emotional intelligence, particularly empathy, when grading.

I'll be honest: When I grade, I try to read student work carefully and give honest, specific feedback in a helpful voice. But the fact is that I often fail. I will get very frustrated at a single student, which then metastasizes to frustration with all my students, when they show flawed understanding of something I feel they should have mastered. I have been known to yell at the computer. I will cuss out students, both specific ones and in general. I will lament the so-called "crisis of disengagement" and wonder how These Kids Today got to be such terrible students (because surely it has nothing to do with me, right?).

In my defense, I used to be a lot worse about this. I was more like the unhappy author of this shockingly cynical Inside Higher Ed essay: Making a lot of noise about how much academic rigor I brought to the table, blaming students for not being up to my standards and demanding that they get in line, or else. You can make yourself feel good for a while by acting like this, and maybe earn some Fake Internet Points in the process. But ultimately you learn that the problem isn’t students, it’s you. Specifically, your inability to demonstrate even the slightest bit of emotional intelligence toward the students you so readily blame.

I recently read this introduction to systems thinking by Daniel Kim and it made me think about not just grading but the students involved in the process. Kim states that true systems have four defining characteristics: They have purpose; all the parts of the system must be present for the system to carry out its purpose; the order in which the parts are arranged affects the performance of the system; and systems will attempt to maintain stability through feedback. On one level: This describes a functioning grading system, as we put in our syllabi. But on another level: This describes the students whom we grade.

When I write that students are human beings — and therefore complex systems of knowledge, experiences, emotions, and beliefs — I really mean this, but I have some distance to travel before my actions catch up to my intentions.

So this year, when I get back to grading (it will start any day now), I will likely pull this article up, read this part of it, and try to remind myself to remember that I was once in the same shoes as my students. My personal life was a hot mess in college and I have no reason to believe my students today are any different; it’s madness to expect me then, or them now, to have it all figured out and act like a polished professional. If want this to be more concrete, I can just look at my own kids, who turn 19, 17, and 14 years old this week and think about their lives, what they’ve had to learn to get to where they are, and marvel at the magic of what it took and still does take for a kid to become a college student.

So, future me: Chill. Don’t yell. Take a breath and remember how it used to be. Then say something helpful when you grade that quiz.

In fact you’ll notice that I simplified his resolution from “Simplify, simplify” to just one “Simplify”.

Thank you for forcing me to reflect on simplicity (or lack thereof) or my system. I have a statement in the syllabus that it is "4000+ words long for a reason". Yeah, the reason is that I'm flawed and cannot communicate clearly and briefly.

Best of luck for the upcoming semester.

I find the SMARTER acronym even more powerful for goal setting (https://youtu.be/XpKvs-apvOs)

Thanks for another great article! Onboarding is a big goal of mine this semester, too.