How to write standards

A brief guide to one of the central components of alternative grading

Around here, we refer a lot to the Four Pillars of Alternative Grading, that is, the four basic components that we see at work in any form of alternative grading scheme. We1 even made a cheesy diagram for it:

While not all real-life implementations of alternative grading engage all four of these pillars — for example, instructors just starting out with this idea might want to keep points around but allow reattempts without penalty — that one on the left, Clearly Defined Standards, seems to be more universal. Last week’s article on Josh Bowman’s calculus class highlights an effective implementation of clear standards; and as we prepare more of these case studies to share with you in the coming weeks, you’ll see he’s not the only one whose grading system centers on clearly defined standards.

In our experience, writing clearly defined standards is deceptively difficult, and it’s one of the main roadblocks that instructors new to alternative grading face. So in this article, I want to give a brief tutorial on how to write clearly defined standards in a way that supports whatever direction you want to take in alternative grading, and so that it will save you and your students time and effort later.

What is a “standard” and what are standards for?

By “standard” we mean a clear and measurable action that a learner can take to demonstrate their learning of some important topic or concept. Let’s look at each of the ideas in that statement:

A standard is an action. It is a concrete task that a learner performs, typically given by an action verb. While we value learners’ dispositions and internal states of mind, for assessment purposes, only actions will do. That’s because we can’t assess internal states like “appreciation” or “knowing” directly — we can only assess them by actions.

That action should be clear and measurable. We mean “clear” from the learner’s point of view. The action being asked of the learner shouldn’t be hard for the learner to understand. And since standards are in place to give a framework for assessment (see below), we instructors need to be able to observe the outcome of the action and determine what it says about student learning, and give feedback accordingly. Note that measurable does not mean quantifiable; sometimes what a student is learning can’t be reduced to a numerical measure without losing the thing being measured. But we have to be able to observe the outcome of the action and give it feedback.

Standards result in evidence of learning. A standard isn’t just any action but one that provides evidence of what a learner has actually learned. Assessments based on clear, measurable standards are like mini-experiments that collect data on learning, and we instructors then decide what the data tell us. It’s not just an exercise in filling a spreadsheet.

Standards are bound to specific and important concepts. There are two things here: specific and important. A standard that can’t be traced back to one or more specific concepts will lead to an assessment whose outcome is ambiguous and therefore not useful to the learner. And to keep work focused and cognitive load to a minimum, we focus standards on important concepts. This last bit is tricky for a lot of us, because it means deliberately saying “no” to assessing some concepts in the course that we really like or have peer pressure to assess, but which aren’t, in the end, all that important. More on that below.

Why have standards in the first place? It’s because in alternative grading, the purpose of assessment is growth, and the standards will form the basic framework for that assessment. Eventually, we have to give learners real information about what they are doing well and where they have opportunities to grow. By having clear standards in place, the results of an assessment cut through the fog and tell learners the plain facts about their work (in a kind way, and to set the stage for reattempts).

Three levels of standards

Sometimes the term “learning objectives” (or just “objectives”) is used as a synonym for “standards”2. In some formulations of course design, there are two levels of objectives:

Course-level objectives that are high-level aspirational goals for learners over the entire breadth of a course. These are usually exempt from the rules about specificity and action verbs that we just stated because of their high level.

Lesson- or module-level objectives which zoom in on the learning goals for a single week or a single day of a course. These are often highly specific, and exhaustive.

It’s good, and often required by departments and institutions, to have both levels of objectives fully spelled out and aligned with each other. The course-level objectives provide a ready road map about what the course is really about, ready for later reference. The lesson-level objectives show what those course-level objectives look like on a day-to-day basis.

But in my experience there is an issue with thinking about objectives in this two-tiered model: Namely, if you just make the lesson-level objectives your “standards” as measured by your assessment and grading scheme, you can very easily end up with more standards than you can possibly assess, or want to assess — maybe a lot more. In my very first attempt at alternative grading, for example, I went through my entire course lesson-by-lesson and wrote down everything I felt my students should do in the course, and made those my standards — and in doing so, I committed to assessing them. All 68 of them, over and over again for 15 weeks. Let’s just say that wasn’t optimal.

What I eventually learned is that there are some topics and concepts that students might encounter in my course, that I don’t really need or want to assess. Instead, several specific lesson-level objectives might fit together as part of a group of similar topics, and I want to assess student learning on the group. So there’s a third layer of objectives where our standards in a course reside, in between course-level objectives and lesson-level objectives. We’ll call those the assessment-level objectives. These are your standards, in our language. They are learning objectives that are clear and measurable, but we filter out what we don’t really intend to assess and group the rest thematically:

An example is coming up. But first, let’s get to the point of this article.

How do you write standards?

Writing good standards for a course is neither a science nor an art form — it’s more like a craft, rooted in good science but requiring experience and creativity to do well, as well as a commitment to improving the process through practice. If you want to see standards that have already been written up and used in real classes, you can find some at the bottom of this webpage.

There’s no one right way to do this, but here is a process for writing standards for a single lesson that’s worked well for me. Once a person masters this process for one lesson, it’s simple to scale up to a unit or an entire course.

Look through the lesson and brainstorm all of the topics and concepts you’d like learners to encounter.

Go through that list and remove anything that isn’t really essential.

For each of the items remaining, ask yourself: What concrete action can students perform that would provide useful evidence of learning on this topic or concept? Then reframe the list item as a task, using a concrete action verb.

A word about phrasing here: We recommend the following template for writing standards, whether at the lesson level or the assessment level:

I can <action verb> … <conditions>.

For example, I can explain the meaning of each part of the limit definition of the derivative in terms of secant and tangent lines; or I can compare and contrast differing views on the causes of World War I; or I can write working Python code to implement a variety of sorting algorithms.

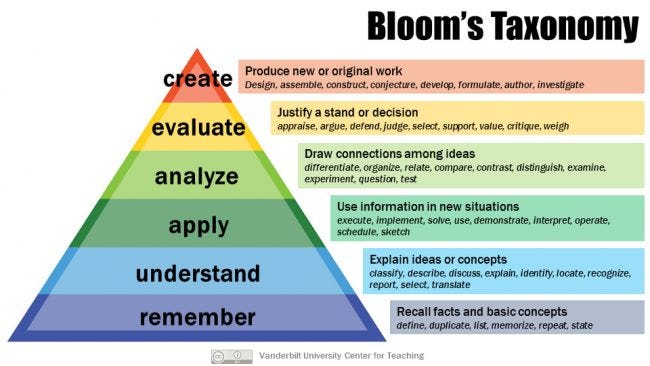

The action verb, as we’ve said, should be concrete, clear, and measurable. Bloom’s Taxonomy is a good source of such verbs, and the usual pyramid visualization of Bloom’s Taxonomy can help you make sure not to concentrate too many standards into one corner of the taxonomy:

The conditions part of the template clarifies and refines the action being taken. For example I can explain the meaning of each part of the limit definition leaves the door open for a variety of “explanations”, including some that you as an instructor may not want to see. Attaching the condition …in terms of secant and tangent lines makes it clearer what students should do.

Having gone through the three steps above, you now have a list of lesson-level objectives. To turn this into assessment-level objectives, look at your list and do the following:

Ask yourself: Can I handle the amount of work that assessing and reassessing every single one of these items entails? If the answer is “yes”, then congratulations, you’re done. But the answer is almost certainly not going to be “yes” if you’ve been thorough in the first three steps and you’re honest now. So quit fooling yourself and move on:

Look at your lesson-level objectives and ask yourself: How might I group some of these together thematically and consolidate them into a single assessable standard? Identify all such groups. Also, ask: Are there any objectives that are important as things to learn, but not important as things to assess?

Then, for each of the groups, frame how you will assess the standard, again using clear and measurable terms and action verbs. For each of the topics that don’t need to be assessed, skip them (but leave them as lesson-level objectives).

For the assessment-level objectives, a.k.a. standards, we want a balance between specificity and generality. A standard should not be so finely-grained that we have many micro-sized standards, resulting in an unreasonable workload for everyone; but it also shouldn’t be so broad that it covers too much and results in data that are hard to interpret.

Example: First-year Seminar

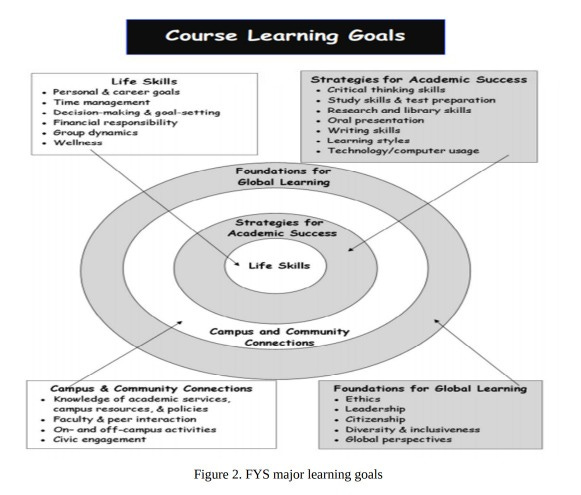

Let’s look at a made-up example that should be accessible to everyone reading this: A first-year seminar course for new college students. Many colleges and universities have such a class, where new students learn about “how to college” — with topics often including note-taking practices, career planning, academic honesty, wellness, and more. Here’s a very detailed example of one such course offered by Bronx Community College. From that whitepaper, here’s a diagram showing the seminar’s course-level objectives:

Courses like this, incidentally, are excellent places to use an alternative grading system. So let’s pretend we’re teaching this course using an alternative system, and it’s time to plan a lesson on time management3. Let’s suppose that we’ll be having students learn about time management in a single lesson.

First, we go through the lesson and brainstorm all of the topics and concepts you’d like learners to encounter. Don’t discriminate, and don’t be too particular about phrasing. For example here is a partial list of what I might come up with:

The importance of time management to being a successful student

Students’ pre-existing ideas about time management

Procrastination — what causes it, psychological tools for avoiding it

Specific techniques: The pomodoro method, time blocking, commitment inventories, GTD

How to plan your weekly work

Different tools for time management: Task management systems (free ones, paid services), calendars, timers

Practice with making out a schedule and time blocking

Choosing a partner to hold each other accountable through the week re: time management

This is just what came out of my brain when I “stormed” it. I might not address all of these; maybe I am working from a fixed curriculum that all first-year seminar instructors are supposed to follow. Some of these (like the last one) are not even “topics”, but activities I’d like to do. So your mileage may vary here; the point is to get all the potential topics out on the table without being too formal about it.

Now I need to look back through this and ask myself: Is there anything I can cut? The answer to this is almost always “yes”. We usually pack way too much material into a given lesson, and as a result we sacrifice depth for breadth. At this stage, we do ourselves a favor by removing inessentials — even if it hurts. For example, I’ve listed Getting Things Done (GTD) as a specific time management technique. If you know me at all, I am a near-religious GTD devotee and would love nothing more than to take an opportunity to evangelize about it. But if I’m being honest: That topic doesn’t fit here. One minute of Googling on this topic will convince anyone that it’s way too big and complex to fit into a single lesson, even if it were the only topic, which it isn’t4. So out it goes. And do the same to any other topic that doesn’t fit, either by size or by relevance.

The third step is to translate everything left over into plain language using concrete action verbs. For example “The importance of time management to being a successful student” might become:

I can explain how time management is important to being a successful student.

It’s a small but important change. It’s no longer just an idea but something a student does. We could have used poor language and said something like, “Students will understand how time management is important to being a successful student.” But how do we know if a student “understands” this? It will happen because they do something, and “Explain” is what they will do. We could add conditions to this as well to clarify, such as:

I can explain the importance of time management to being a successful student by keeping a journal and reflecting on my entries.

This begins to blur the lines between standards and objectives. You may like that! Or you may want less specificity than that. Or you may want students to do something other than “explain”. You have a lot of freedom, as long as the language is clear and measurable.

Here is a possible list of lesson-level objectives obtained by simplifying the initial list and converting to actionable phrases:

I can explain how time management is important to being a successful student.

I can explain the causes of procrastination.

I can implement specific actions to avoid procrastination.

I can write a brief description of time-blocking.

I can write a brief description of the pomodoro technique.

I can create a weekly schedule for my school and life commitments.

I can use a computer or mobile device to track my time.

I can work with a partner to hold each other accountable for effective time management practices.

This list serves as our lesson-level objectives. But you might notice that while they are all good objectives, they aren’t necessarily good standards because looking ahead at assessing these, it’s not clear that every single one of these should have its own assessment or even be assessed in the first place. For example, do we really want to assess students’ ability to describe both time-blocking and the pomodoro technique separately? And do we want to assess “working with a partner” at all?

That’s the gist of step 4 — being honest with the workload that assessing each and every one of the lesson objectives entails. It’s clear to me that these are more objectives than I can commit to assessing. So now we activate step 5: Can we group some of these into thematically-linked objectives that can be assessed as a single standard? (And are some of these topics that shouldn’t be assessed at all?)

I can definitely lump the two objectives about specific techniques together; and I don’t think I really want to assess that last bullet point, since it seems overly intrusive to do so. (However if you’re teaching the lesson, you can certainly disagree with me on that!) It also seems like I could group together the two points about procrastination. Continuing in this vein, I might come up with this final list of standards:

I can explain how time management is important to being a successful student.

I can explain the causes of procrastination and describe specific actions to avoid it.

I can write brief descriptions of specific time management techniques, including time-blocking and the pomodoro technique.

I can create a weekly schedule for my school and life commitments.

I can use a computer or mobile device to track my use of time.

I say “final”, but if I’m writing all the standards for each lesson before the start of the semester (see below), I might want to pare this list down even further, to maybe just 2-3 standards of the highest importance whose assessments will help form the course grade.

Mistakes that can be made

Writing good standards isn’t easy, and there are plenty of ways to mess it up, such as:

Writing standards that are too fine-grained, for example my initial list above which had separate objectives for two different time management techniques. Again, those are OK as lesson-level objectives but don’t work particularly well on the assessment level, because you will end up with more assessments than you can manage, and often each assessment is on a fairly low Bloom’s Taxonomy level.

Writing standards that are too broad, for example if I combined the first two standards above to I can explain how time management is important to being a successful student, explain the causes of procrastination, and describe specific actions to avoid it. This is now a “double-barreled” standard that assesses at least two different things; it’s more than one assessment can reasonably handle and it’s overly complicated.

Writing standards whose conditions are too specific, for example I can create a weekly schedule for my school and life commitments using Google Calendar. There is probably no reason to restrict students to using Google Calendar, and a more permissive standard would be better.

Writing standards whose conditions are not specific enough, for example I can create a weekly schedule. A weekly schedule of what exactly?

Writing standards for things that aren’t really necessary or important. This is what happens when step 4 breaks down and we include stuff in a lesson that we feel is important, but really isn’t important to the learners — like my overview of GTD. Save those for special topics, or a blog!

Above all, the biggest mistake one can make is failing to keep things simple. Using plain language, an active voice, simple action verbs, and clear tasks limited to only the most relevant things to learn, is essential to any standard.

What to do with standards

My personal practice regarding standards is to spend an entire day well before the start of a semester, going through each course lesson-by-lesson and writing up the standards for each one. Then that master list of standards becomes the raw material for the rest of the construction of the course — especially the assessments.

For example, here’s the master list of standards from my Fall 2021 Discrete Structures course. There are 20 standards overall (I called them “learning targets”), which I got by going block-by-block through my course one morning and identifying just the items in each block that I felt were so important that I could commit to repeated assessments and reassessments throughout the semester. It’s a far cry from 68 standards! Still, my first pass through the course yielded 28 standards, and I made some tough choices to cut a few, and did some consolidation of others to get to 20. I would have preferred 16.

Once standards are written up, you can use them to design the active learning work that your students will do: Class activities should provide ample practice with the tasks spelled out in the standards. Then, crucially, you can begin to plan the assessments you’ll use in the course — quizzes, oral exams, written work, projects, or whatever else you have in mind. There should be a direct alignment between standards, activities, and assessments as well as the course tools and materials you choose and ultimately the grades that are assigned:

If done well, the assessments and activities in your course should be almost self-aligning because they are just instances of the standards. For example in our first-year seminar course, we have the standard of I can use a computer or mobile device to track my use of time. What class activity could students do to practice this? Well, how about actually practicing with different tools in a group that can help each other? And how might this standard be assessed? Perhaps by asking each student to actually demonstrate their use of a tool of their choice, for example in a time tracking journal?

Once standards are written, in other words, they become a tremendous time- and labor-saving device for you and your students, because each standard contains the seed of its own practice activity and assessment.

Where you go from here with standards, is a function of how you want your grading system to work. For those using standards-based grading, your entire course is based on demonstration of the standards. For those using specifications grading5, the standards could form the core of one or more of the “bundles” used in specs grading. Even those using ungrading can benefit from the standards, since they can be used to structure student activities and assessments even with no formative grades being given.

But one thing that you should definitely do with standards for your course is go public with them — share them generously with your students, and also with everyone! You should be proud of the work you are doing and excited to share the fruits of your hard work.

Thanks for reading! Did you find this article helpful? Do you have any disagreements or points you want to amplify? Let us know in the comments.

OK, I made this. David tolerates it. Any graphic designers out there who want to improve on this, please leave a comment!

I don’t believe “objectives” and “standards” are truly synonymous; there are some subtle differences. But they’re close enough for what we’re talking about here, and common enough that this section matters for people new to this conversation.

Having a single, discrete lesson on time management might not be the best approach for teaching time management; you might for example prefer to have a running series of discussions rather than one lesson. Or maybe you want two lessons on it. But for the sake of argument, let’s assume there’s a single class where this is the main topic.

And technically GTD is not a “time management technique” but a complete philosophy on the management of attention and commitments. But now I am evangelizing.

Note that standards and specifications aren’t exactly the same. A standard is a task to perform; a specification is a description of what success on a task, or some other unit of student work, looks like.

I will be borrowing your use of the term "learning targets." Other terms (like standards, objectives, competencies) are used so broadly that people might assume I mean one thing when I actually mean another. With the term "learning target," I can define exactly what I mean in the syllabus and (hopefully) avoid confusion

I’m still not sure I understand the difference between level-lesson objectives and learning targets, with respect to grading. For example, consider a unit on polynomials with a standard as the following: “I can add, subtract, multiply, and divide polynomials.” This standard would consist of several lesson-level objectives e.g. let’s say six. If I’m assessing a student on this standard aren’t I essentially assessing them on the objectives that make it up?