Planning for grading for growth: Hitting the mark

Focusing on simplifying and marking assessments in your alternative grading system

The start of the new year is just around the corner, and we're doing a multi-part series on how to build an alternative grading system into your courses this fall. Although the first day of classes is getting closer each day, there's still time to build a great alternative grading system into what you are already planning. (You are planning by now, right?)

In Part 1, we investigated the who, what, when, where, and why of your course. In Part 2, we set up the module structure and standards. And in Part 3, we examined the primary focus of the course and wrote out a general plan for assessments.

In this fourth installment, we'll be bringing the build process down to a lower altitude and focus on two specific items: the marking methods you'll use, and your framework for course grades.

But first, simplify

If you've followed the first three parts of this series, then at this point you have, among other things, a general list of assessments. If you're like a lot of instructors, this list might be very specific — and way longer than what you can possibly implement (papers and quizzes and weekly journals and a project and...). Before thinking about the details of how you might mark an assessment, take a second to get that list into shape.

First, simplify your list of assessments by looping through your list and asking:

Does it align with the primary focus of the course?

Does it align with the learning objectives?

Is it worth the time and effort of reassessment?

Do my students have the personal capacity to complete the assessment? (That is, is it reasonable to even give this assessment, or does it demand too much from students outside of class time?)

Does this item need to be assessed at all? (Perhaps it can become a class activity, or simply doesn’t need to exist).

As you ask these questions of each of your proposed assessments, if any of the answers is “No” — even if the answer is “Yes” but you’re even slightly tentative about it — then reconsider that assessment, either by modifying it or, perhaps better, by cutting it from your course plans (at least temporarily, to see how it feels without it).

Once you’ve slimmed your list down, categorize what's left over into groups that indicate who will grade the work, and possibly how1. These categories include:

Assignments that the instructor (or possibly a TA) must assess and give feedback on.

Assignments that would work well with peer feedback.

Assignments that could be automatically graded.

Assignments that need to be checked only for completion and/or effort.

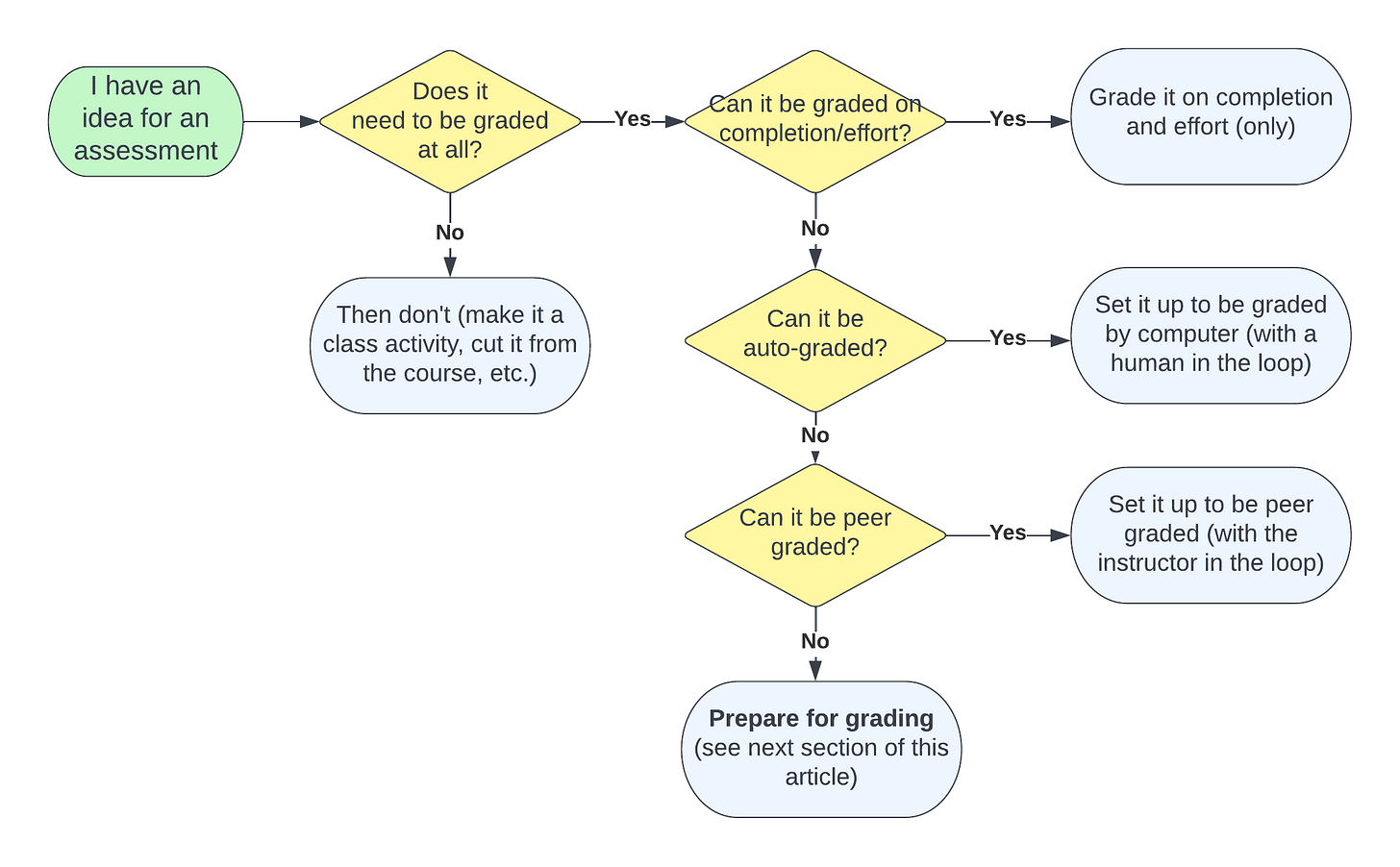

Key to understanding these categories is that not all student work needs to be graded at all2, nor does it need extensive evaluation; and even if it does, you don’t necessarily need to be the one grading it. In my mind, I think of the categorization process here as a flowchart:

What's the mark?

So you now have a list of assessments that make sense for the course, for you, and for your students, and you know which assessments you’ll actually grade. Now we have to think about how to mark them.

Remember that by "mark" we mean an indicator of progress placed on student work. In traditional grading, the mark is typically a percentage or point value; in other systems, it might be a brief description (“Satisfactory”, “Needs Revision”, etc.) or a symbol (“S”, “R”, “😀"). As we mentioned here, we use the term “mark” because the more American word "grade" has different but related meanings: It could mean the mark on student work (“I got a grade of 87 on the exam”), the final result of a course (“My grade in the class was B-”), or a student’s academic level (“My son is in the 8th grade”). We adopt the term “mark” to mean the first of these3.

As I said, you’ll now need to think about how you intend to mark the assessments that you will be evaluating. For now, you’re just deciding what the marks will be, not the specifications or rubrics by which you will assign them. (That comes later.) Remember the idea from the Four Pillars is to give Marks that Indicate Progress. Some options we have seen include:

Don’t give marks at all, just feedback (i.e., use ungrading). Ungrading, as we’ve seen, works well for assessments where you want students to focus on the feedback you give them, without the distraction of extrinsic motivators. In our view, ungrading can be applied selectively as part of a larger system that includes graded work. That is, we think there is such a thing as “partially ungraded courses”, and you do not have to commit to a fully ungraded course right now. See the example below from my Discrete Structures course for how that might work.

Mark using a two-level scale. The “Pass/Fail” or “Satisfactory/Not yet” approach is the canonical option for specifications grading and can be a good fit elsewhere. In this approach, the assessment is given clear specifications for what constitutes “acceptable” work, and student work either meets those standards or it doesn’t. (We highly recommend not using the word “Fail” here, for obvious reasons.)

Mark using a three- or four-level scale. A three- or four-level scale, such as the EMRN rubric, is useful if the assessment has more nuance to its outcomes. For example, if you want to distinguish between work that is merely “good enough” from work that is “outstanding”, then you might use a three-level setup like Excellent/Meets Standards/Revision Needed. Both Excellent and Meets Standards indicate work that meets your standards, but Excellent identifies work that goes beyond the minimum required. The EMRN rubric adds a fourth level, “Not Assessable” (N), to indicate work that does not meet the standards, but for a specific reason: There’s something seriously wrong with the submission (parts were left off, some vitally important instruction was not carried out, there are so many errors that the best thing would be to just start over, etc.).

We do not recommend using more than four levels of marks for any assessment. Doing so does not yield better information about student learning, so it’s not worth the effort of tracking at that level of detail. (Remember: Keep it simple.)

What does a C look like? What about an A?

A completed grading system will need to include not just the details for how marks on individual assessments are given but also how those marks translate into a letter grade for the course4. We will get into letter grades in detail in an upcoming post. But at this point, it’s helpful to draft some criteria for just two grades: C and A.

These two letter grades are useful bookends for student work in a course. A grade of "C" typically refers to an overall body of work that is minimally passing. A grade of "A" indicates an overall body of work that is excellent or exemplary. Write a short narrative description or bullet-point list that answers these questions:

What characterizes student work that is minimally passing (i.e. “C-level”)? What does it look like to an outsider, examining that student’s body of work? Focus heavily on the minimal part here: Is everything you wrote really essential to passing the course? If not, it shouldn’t be here.

What characterizes student work that is exemplary (i.e. “A-level”)? What does that look like?

Write these without being too fine-grained or specific, but detailed enough to be meaningful. We’re looking for a narrative description here, not a table of requirements. Create something you could hand to a colleague to see if they agree.

Of course, you should modify our advice as needed if your context requires different meanings for some grades. For example, your institution might view “D” as the minimum required for a prerequisite course, in which case you should begin by writing a description for “D” instead of “C”. Likewise, your students may need to earn a B- or higher to be eligible for admission into a future program; focus on setting “B-” requirements first.

This process will be helpful later in several ways. First and foremost, making the hard decisions about what a “C” should include will help clarify your thinking about what matters in your course. It may even make you want to delete or change some assignments. As we’ve interviewed alternative graders, many have told us how the process of setting grades forced them to rethink their course requirements. Second, you can use these descriptions later to reality-check the finalized grading process in your syllabus. It’s easy to craft specific requirements for a C or an A, only to have students actually earn a C or A and it feels wrong because their work doesn’t match what you believe those grades should represent. The narratives here can look ahead to see if your actual grade requirements will produce the results you expect. Third, once we have a strong idea of what a C and A mean and spell out the specific requirements, it will be a lot easier to determine how to earn a B or D.

What this looks like for my Fall classes

This Fall, I'm teaching two sections of Discrete Structures for Computer Science 2. This is the second semester in a sequence whose first semester I taught back in the Spring and it’s the first time I’ve taught this since 2017. I'm following along with this how-to series along with you.

My initial list of assessments that I ideated had things on it that seemed like a good idea, and I’d used them in the past, but upon reflection I ended up cutting them. For example in the 2017 version of the course, I used “engagement credits” to entice students to do things like attend class, complete surveys, post on a discussion board, and so on, and those credits were part of the final grade. As I went through that list of questions above, though, I decided that (1) “engagement” didn’t indicate learning clearly enough (keeping Feldman’s “Grading for Equity” in mind) and (2) the bookkeeping on engagement credits was too much work. So I cut it, and I immediately felt better.

Going through the assessments that survived the simplification process, I decided how to mark each one:

Daily Prep assignments; mark Pass/No Pass5 on completion and effort only.

Learning Target quizzes over content standards; each attempt marked Pass/No Pass on completion and correctness.

Proof assignments; do not mark, just give feedback and indicate clearly to students when their work has met the standards.

Application assignments; same.

(Later, I’ll write up specifically what goes in to earning these marks — but not right this minute.) I then came up with the following descriptions of "C" and "A" work:

In MTH 325, a C means: A "C" student has demonstrated competency on all the "must have" content skills: They can break down and analyze a proof. They can do basic computational work with the fundamental structures of graphs, trees, and relations.

And they have shown consistent engagement with the class most of the time.There's room for improvement, but they have the tools they need to do well in classes like CIS 263 [the intro Algorithms course in the Computer Science department].In MTH 325, an A means: An "A" student has demonstrated skill on nearly all of the fundamental content skills, not just the "must haves" but also nearly all of the "nice to haves". They have also aggregated a body of work in the course that shows skill in both the theoretical and applied areas of the subject: They have not only analyzed proofs but written their own, in a variety of styles and contexts, with sound logic and clear style. They have shown the ability to apply the basic content knowledge to a variety of domains.

And they are consistently engaged with the learning community.

Notice I deliberately left out anything about how many content standards need to be met, how many proofs to write (and how many should be "excellent" versus just "adequate"), and so on. It's pretty abstract and that's the right tone for this stage of the build. From here, I will add the details.

You’ll also notice the struck-out text about “engagement”. I realized I was asking for “consistent engagement” from all students. But if “engagement” doesn’t distinguish a C from an A, why include it in the descriptions? I’m not planning on flunking students because they are “disengaged”, so that shouldn’t be in my narrative; so I removed it. (And what even is “engagement”?) But I leave it here to highlight my thinking process, and to show how hard it can be, even for old and grizzled alt-grading practitioners, to separate what we think a grade should involve from what we are actually prepared to assess. Old habits die hard.

Moving on from here, we’ll next design how feedback will take place within this somewhat detailed system we’re building out.

Credit goes to Renee Link, Professor of Teaching in the Chemistry Department at University of California-Irvine for this idea and the categories that are listed.

By this, we mean the work doesn’t need formal evaluation at all. We mean this as being distinct from ungrading the work, where you formally evaluate it but don’t put a mark on it. For example, you might take a writing activity that you had planned on assessing and including as part of students’ formal body of work in the course and decide, Let’s just do this as a formative in-class activity and have students give each other feedback, thereby giving students an activity with feedback but not “grading” the activity.

There’s been some disagreement here at the blog about whether anything other than a numerical point value constitutes a “mark”. David and I interpret this term liberally to include any indicator of progress. But others disagree in good faith and say only numbers can be marks. We will agree to disagree on this point.

Someday we might be able to drop letter grades from the university experience altogether, as places like Evergreen State College have done. Until that day, we'll need to take letter grades into account to keep the registrar happy.

I don’t particularly like “Pass/No Pass” but I’m struggling to come up with something better. Twitter had suggestions.

Just before my mini-vacation long weekend, I sat down and tried to do this step on Friday! I will be pleased to go back into the office tomorrow and look over my notes in the context of this post. Thank you for the flow chart and categorizing that matches up with what I was trying to do last week :)