Doing alternative grading on a short schedule

How does alternative grading work when you cut the length of the semester by more than half?

Throughout this blog, David and I have been working hard to show how alternative grading practices work not only for courses that fit our norms, but also for the “what-if” courses. What if your class has 200+ students? What if your situation calls for more than one approach to grading? And more. One of the “what-if” scenarios we haven’t seen has to do with time, specifically: What if your class had all the content of a 14-week course, but it’s compressed into a 6-week schedule?

That’s my situation right now. Our university offers two six-week terms in the summer, one called “Spring term” (May through mid-June)1 and the other called “Summer term” (mid-June through early August). I’m currently teaching a version of my Discrete Structures class which I’ve written about before, this time in the Spring term. The highly compressed time scale poses some interesting challenges for doing alternative grading, and in this post I want to write about those challenges, what I’m doing to address them, and how it’s going as we enter into week 2 of this course.

The setup

Teaching in the summer isn’t all bad. The class sizes tend to be a little smaller, the atmosphere is more relaxed, and typically (but not uniformly) students are taking a lighter schedule so they’re being pulled in fewer directions. The pay at my university is very good too. Despite all that, I told myself a few years ago after teaching in the summer that I valued time more than money, so I was officially retiring from summer teaching for good. So when my department chair asked me in March if I’d consider teaching a Spring term section of Discrete Structures for Computer Science 1, despite the fact I enjoy the class and have taught it many times (and therefore have all the materials already built), I politely said no thanks.

But then, this year, my middle child somehow turned 16 and got her drivers’ license, and needs a car. Reluctantly, I decided that teaching a class that I enjoy and have basically already built, for just six weeks, in exchange for almost-used-car-size cash infusion2 wasn’t a bad deal. As I said, I’ve already built the courseware and the assignments; I just had to remix what I already had built, to make it work in a 6-week format instead 14 weeks.

It didn’t take long to realize that compressing the course into less than half its original schedule was a big challenge.

Just do the math: This is a three-credit course, so in a typical week in a regular semester the class would meet for 150 minutes. But on the compressed schedule, we meet 90 minutes per day, times four days, for a total of 360 minutes each week. So one week in my course is worth over two weeks in a regular semester. On a moment-by-moment basis, the class moves at the same pace no matter the schedule; but there is more done in a single class meeting, and there is dramatically less time in between meetings.

I don’t have the space here to get into all the issues this kind of time scale imposes on students (and on me), but you can probably list several just by imagining yourself as a student in the class3. For this blog post, I want to focus just on the challenge posed for an alternative grading structure --- one that, as we’ve said before, is predicated on the idea that learning takes time. How do you do it, when there’s virtually no time?

The challenges

From the standpoint of the grading system, running a course in less than one-half the usually schedule poses at least the following issues:

Deciding on the amount of evidence needed to meet a standard. Alternative grading systems start with Clearly Defined Standards, and we ask students to provide evidence that they have met at least some subset of those standards. But how much evidence is enough, and how much evidence is realistic to expect in such a short time frame? In the past, my Discrete Structures course has had 20-ish standards (called Learning Targets) and students needed to provide two successful demonstrations of skill on a Learning Target in order to meet the standard. In a semester that lasts 3-4 months, this is no problem; in one that lasts a month and a half, it starts to feel impossible. And all of the simple solutions — cutting back on the number of Learning Targets total; cutting back the number needed to earn an A or B; scaling back the amount of evidence needed — feels like dumbing down the course.

Providing students enough opportunities to reassess. Similarly, alternative grading is based on the idea that students can Reattempt Without Penalty if they assess on a standard and don’t make it. In a 14-week semester, it’s usually not a problem for a student who maintains awareness of the calendar to have enough opportunities to retry assessments to the point where they can truly eventually show what they know. But in six weeks, even if a student is diligently taking care of business with respect to assessment and reassessment, it could easily start to feel like the class is just nothing but endless daily assessments; and if a student just needs time to think, they may not have it. That’s especially problematic for standards that don’t appear until the end of the semester: A Learning Target that doesn’t come up until the next-to-last week of a 14-week semester doesn’t come up until the next-to-last day of a 6-week course.

Providing feedback that’s timely enough to be useful. Then of course there is the grading itself, which we frame as providing Helpful Feedback. Feedback has to be given promptly in order to be truly helpful. I pride myself as a relatively fast grader, but with everything else happening on a compressed time scale, my feedback has to become even faster or else the first two challenges for students become a lot harder. Am I up for that?

Confession: At one point, I thought about addressing these challenges by just reverting — just this once — back to a traditional, points-based, three-tests-and-a-final system. After all, none of the above are issues if you don’t center your teaching on feedback loops. That would be easier for everyone, right?

But in the end, I decided to tough it out, because what good would it have done to go back? A traditional approach would be easier but it wouldn’t add days to the calendar or hours to the clock. And students would still need the feedback loops – I just wouldn’t be providing them, not because withholding feedback loops is best for students but because I was avoiding hard problems. And my mantra ever since March 2020 has been, we can do hard things.

The approach

In the end, my grading system for this version of the Discrete Structures course looks a lot like the one for the 14-week version:

There are 21 Learning Targets and students provide must provide two “successful demonstrations of skill” on these, usually through taking Learning Target quizzes that are cumulative (here are the first two: Quiz 1, Quiz 2), but there are alternative methods as well, see below. Each demonstration is graded Success/Retry.

There are also a handful of Application and Extension Problems (AEPs), scaled down to six of these from the usual 10. These are graded using the EMRN rubric.

There are Daily Prep assignments for each class where students learn the basic concepts of new material. There are 20 of these (usually it’s around 30, but you know, time scale).

A new addition is the use of WeBWorK to provide 10 simple practice problems a week, graded using points (there’s no way to change this), at one point per problem. These are auto-graded by the software.

And there’s a final exam that is a pretty light affair — a few reflection mini-essays and a final recertification on the core Learning Targets.

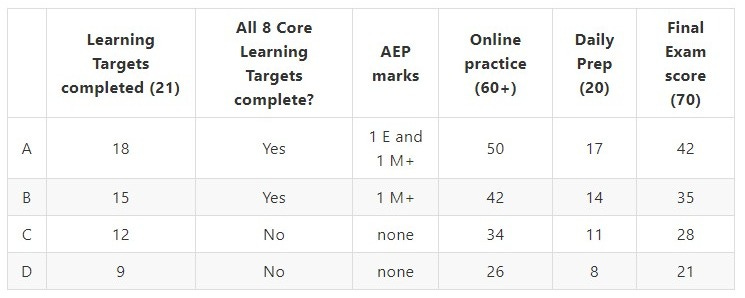

Students’ course grades are determined using this table:

Here’s the syllabus with all the details. I borrowed heavily from Hubert Muchalski's organic chemistry course which was one of our case studies from earlier. Hubert’s approach in turn borrowed from me, but he made some improvements that I really liked. Remember kids, sharing is caring.

So this 6-week class ended up looking pretty much like the 14-week version. But I’ve made four significant changes to address the shortened time scale.

Each class meeting focuses on one Learning Target. I had an epiphany back in April while I was building out the class schedule: There were 21 Learning Targets I’d identified, and 24 class days. So I could reasonably build the schedule so that each day focuses on one Learning Target (on average). This approach has really paid dividends so far. Having a simple and clear focus for each class meeting means we spend time more efficiently, and students are clearer on the standards themselves since we spend an entire day on each of them. It’s even helping me free up time in the schedule despite how compressed it is: I was able to schedule three “TBA” days at the end of the semester with no content coverage, and this should be crucial for giving students more time for reassessments.

There is a much tighter integration between the standards, the class activities, and the assessments. I’ve written before that there should be a direct line of sight between course standards, class activities, and assessments. In a class on this tight of a schedule, I believe the key is to make that alignment as tight as possible by starting with the standards, then building the class meetings as times to practice on those standards, then building assessments to mirror what students were practicing. For example, this Tuesday the learning target of the day is I can write a set using roster and set-builder notation. After doing Q&A on the Daily Prep, we’ll spend most of the class simply practicing writing sets using roster and set-builder notation. Then eventually students will demonstrate skill on this learning target by, you guessed it, writing sets using roster and set-builder notation. This may sound like “teaching to the test”, but it isn’t. In “teaching to the test” you start with the assessments and work backwards to the activities and then to the standards, so that every standard becomes “I can pass a test”. Here, we’re starting with a Clearly Defined Standard that specifies what students should be able to do, then we practice doing it, then finally students show whether they can eventually do it or not.

I’m committing to a “truly flipped” course design to allow more time in class meetings for assessment/reassessment. This may sound strange, especially if you know my history with flipped learning — was I not using flipped learning before? Well, yes, but actually not really. In the purest form of flipped learning, there’s little to no direct instruction in class; this is put outside of class in the form of guided activities, and it’s replaced in class with active learning. In my past classes, I realized, there was still a lot lecturing and re-teaching despite having pre-class activities. This time, I’m realizing that in order for students to do what they need to do on the short schedule, we need to do a lot of practice and assessment in class. So I’ve built the course so that as much of the graded work as possible is being done during our class meetings, including Learning Target assessments. This requires that I pay close attention to what I give outside of class — it has to be focused on meaningful preparation, it has to be of a high learning value, and it can’t be too much for students to handle in a single day (because there are four of these due each week, most on consecutive days).

I’m using a wide-open policy for alternatives to demonstrating skill on the Learning Targets. To demonstrate skill on Learning Targets, the primary method is to take Learning Target quizzes (which they have some time to do during class meetings). But it’s not the only way! They can also schedule time during drop-in hours to do oral quizzes, and they can do asynchronous “quizzes” by making videos of themselves on Flipgrid. (I’ll save the details for a later post.) I’m also telling students that anything they consider evidence of skill, they shold bring to me so we can talk about it and I can ask them more questions. For example, students might choose to use an AEP as a demonstration of skill, or even an assignment from another class. I’m keeping a broad view of what constitutes “evidence of skill” and letting students get creative about what they use. I’m hopeful this will ameliorate the issue of having enough time to do reassessments.

How it’s going

Today, we are starting the second week of the course – which is equivalent to the middle of the third week of the course on the usual schedule. As far as how things are going, I’d say: So far, so good.

The students have seen this grading system before in some of their math courses, and I’m happy to say it’s starting to metastasize into the Computer Science department with a number of our faculty there trying it out and liking it. In both areas, students may need some help understanding the details of the system but they definitely like the overall approach. It’s still early and so there’s a lot of time for things to get totally f-ed up, but I am cautiously optimistic.

I’m collecting data every day about how this is playing out with students, and pretty soon the feedback loops will be in high gear. (We haven’t assigned any AEPs yet, for instance.) Here are three things I’ve learned so far:

Having Clearly Defined Standards makes everything easier. For students, the standards keeps them focused and the list cuts through the barrage of assignments and information to give them a clear signal of what’s expected of them. For me, I’ve found once I have the standards written out, the class meetings almost prepare themselves — I know what I’m focusing on, and I just need to prepare an activity that instantiates the standard of the day, and be ready to observe and field questions.

What’s important isn’t just flexibility but options. We talk a lot in the pandemic era about the value of flexibility4 but flexibility doesn’t mean much if there aren’t options available. I’m starting to think that “A variety of ways to demonstrate skill” might be the unofficial fifth pillar of alternative grading — it certainly is making a big difference in the overall comfort/stress level of students as they face down high academic standards on a very short time scale.

Despite everything having to do with the calendar, students still prefer this way of grading. I’ve joined a Zoom breakout room (this is a synchronous online course, by the way — does that alter your perception at all?) a few times when groups have finished a little early and caught them in mid-conversation about the grading system, and it’s all positive. “Makes much more sense for the way I learn”; “fits better with how we learn computer science”; “takes a lot of the pressure off” are among the snippets I’ve overheard.

It’s still going to be very important to communicate with students often about how they’re experiencing all of this and be agile with corrections to the course if they’re justified. But at least for now I’m happy to say that alternative grading isn’t rendered impossible by running the course at 2x speed.

Insert joke about Michigan winters here.

As recently as two years ago, the summer pay would have been the size of about two used cars, but I digress.

There is absolutely no way I would have taken a three-credit 6-week class when I was a student — I need time to think, and I would have been instant roadkill in a class like this. I asked my students why they were doing it, and most said that it was their only option in order to stay on track in their degree programs.

How many emails have you received from department chairs, deans, etc. in the last two years that include the statement “Thank you for being flexible”? And do you flinch every time, like I do?

There's a big push at my institution to convert traditional 16-week courses into 8-week courses. The super-simplified idea is that a student could be more focused on two double-speed classes at a time, rather than four normal-speed classes.

I'm curious to hear from others (a) whether you are having a similar push and (b) if you think it is a good idea.

I'm reading this while preparing to teach Spring[1] Intersession course (3-week suicidal pace, 1 day = 1 week of regular semester). If you don't hear back from me, it was my pleasure to know you.

But in all seriousness, your blog and your open source materials are immensely helpful. I was considering, but hesitant, to do something similar to #4 on your list of changes. Thanks for pushing me over the fence.

Do I understand it correctly, that you are assessing LTs as via "one and done" method? Is that a permanent change or compromise related to the compressed schedule?

If I do come back after this as a sane human, it will be thanks to the community and the vehicle that my middle schooler will inherit in 2 years will have this carved on the dashboard: "This gift was made possible by David Clark, Robert Talbert, Growth Grading Community, and the students like you"

[1]: Insert your Central California joke here. Roses are past their peak bloom and daily max temperatures in mid 90s.