Tracking Alternative Grades Throughout a Course

Helping My Students Monitor and Determine Their Own Midterm and Final Grades

This week’s guest article is from Prof. Matt Mio, who teaches Organic Chemistry lecture and laboratory courses at University of Detroit Mercy in Detroit, MI, where he is Chair of the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, including Physics. Detroit Mercy is a school of over 5,000 undergraduate, graduate, and professional students with a near 150-year old mission to holistically educate students in an urban context. His midcareer renaissance in using Alternative Grading Strategies (AGS) came about, like many of us, as a result of the pandemic and reading many, many books and articles about modern pedagogy. He has volunteered with the American Chemical Society for over 25 years to advocate for undergraduate science education. When not thinking about carbon atoms, Matt is likely thinking about decorating for Halloween. You can find him on LinkedIn.

I have been teaching organic chemistry at the college level for nearly 25 years. My institution has a diverse student population and a commitment to education in an urban context for nearly 150 years. Science lecture and lab courses enroll at approximately 50 and 25 students, respectively. A long-running trope with year after year of students is how they’d spend more time during final exam week re-calculating their points-based final grade (mostly in efforts to find the minimum needed to pass) than studying for the final exam. This activity stood in contrast to students’ knowing their grade standing at any other time during our courses together. Surprise midterm grades and tough conversations littered the semester as students “discovered” their course standing unpurposefully.

Through this post, I’d like to give the reader a tour of my efforts to help students deliberately track their grades. Incidentally, I won’t be fully focused on describing my specific grading systems, but I welcome contact to do so.

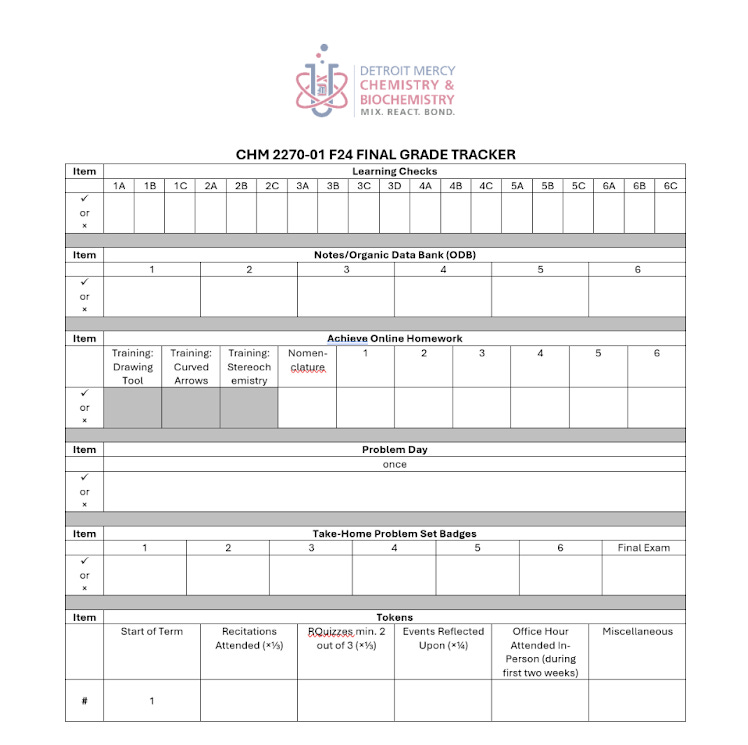

A Grading Track Sheet

About 15 years ago, I devised a plan to eliminate ambiguity and encourage student ownership in their grade calculations: a track sheet. I was measuring students’ performance across multiple dimensions – summative assessments, mini-quizzes, handouts, online homework, extra credit – each with a different points-based structure. The grading schema was likely a little confusing, and I wanted students to gauge their own performance across all these areas, not just read numbers from an online learning management system. The structure of the track sheet allowed students to fill in scored points for each course item in a table which also included possible points. The far-right column instructed students to determine the sum of each course dimension, add those numbers up and divide by the course point total at the time. The result, of course, was a percentage that could be applied to the class’ A-B-C-D-F grading scale. Voila! You had a midterm/final grade, or an accurate snapshot of the grade throughout the semester.

Only things never worked out that way. A few years in, it was clear that students recognized the letter grade scale easily enough, but they (a) did not “feel” the weight of activities/assessments based on point value, and (b) did not regularly use the track sheet as a daily or weekly performance check-in. It was challenging for students to understand how several differently weighted assignments contributed to their overall grade. Anecdotally, I saw very few of my students using the track sheet throughout the term, and I even noticed a few using the sheet incorrectly - for example, including future item’s points or not being attentive to the possible point total for an item. Even from its inception, the concept may have been doomed. Upon showing my partner the template for the first sheet, it took them less than 10 seconds to conclude, “They’ll never use it.”

AGS Track Sheets - Version 1.0

After 10 years of giving students a way to track scores and not observing any daily/weekly student understanding of their performance, I instead adopted alternative grading strategies (AGS) in my lecture and laboratory courses1. The Four Pillars of Alternative Grading (clearly defined standards, helpful feedback, marks indicate progress, reattempts without penalty) now permeate my pedagogy. Through a tight-knit set of learning outcomes, regular feedback, low-stakes assessment, and a token system, my students navigate the world of organic chemistry with more purpose, iteration, and reflection. The AGS in my courses allow me to directly observe and assess a student’s engagement (daily, self-assessed learning checks), record-keeping abilities (checked-in note summaries), use of practice/feedback (handout and online homework), and collaboration skills for problem-solving (literature-based take-home problem sets).

Not specifically covered in this scaffolding is how it translated to a letter grade. I chose to use a “bundling table,” where the number of passed items in each of the five course dimensions corresponds, or is bundled, to a specific letter grade2. Students just count up what they’ve turned in or passed and read across the table. In moving to this model, students have anecdotally taught me that they most certainly care about their grade throughout the term, but without instruction on how to discern it, more pressing academic matters prevail.

Again, the dragon of discontent reared its ugly head. Even after taking an entire class period at the start of the term to carefully explain my AGS rationale and walk students through the use of a now slimmer and trimmer track sheet, something was missing. Yes, students now broadly reported on course evaluations3 that AGS had taken the vast majority of the high-stakes anxiety out of my course and focused students on specific competencies. However, the tendency of students to view the act of letter grading as transactional and beyond their comprehension persisted. In-class anonymous attitude surveys showed that student motivation was low to track their grade at any other point than the last week of the semester.

To solve this problem, I started by trying to clearly define what success at being able to track one's grade would look like:

I wanted my students to be able to project their class grade at any instant during the semester.

I wanted students to possess dynamic, day-to-day grade knowledge to lead to much richer conversations about performance and improvement while there was still time left in the term!

I wanted my students to take independent ownership of the act of grade determination and cease to pose transactional questions to the professor like, “What is my grade right now?”

AGS Track Sheets - Revised

I started by utilizing the existing course reward economy, a token system I designed which allowed for revisions of assessment work or replacement of missed, lower-level items, like homework. This solution presented itself quite early in my experimentation with AGS. After all, students were also keeping track of earned tokens: attending and participating in optional recitation sessions, taking advantage of office hours, early submission of coursework, and passing daily self-assessments (learning checks). As an instructor, I was inundated in those early days with a new question – “How many tokens do I have right now?”

Within one iteration of implementing AGS in my courses, I quickly realized this question had the potential to drive me quite batty, if I let it. When posed, I asked students to rephrase the asking of this question considering the more motivated alternative, “My calculations show I have earned six tokens so far this term. Can you confirm this with your records?” Aha! The evidenced-based framing of this question did not escape my notice. I wanted my students to use the same framing to questions about midterm and final grades, as well.

That first semester, I offered a token as bonus to those who took advantage of the course track sheet by filling it out to determine their own midterm grade and sending a copy to me for evaluation. By meeting a deadline for this exercise, students reflected on their efforts so far and had plenty of time to shape their future energies. I used both email and the Remind class texting app to communicate with students. I will be honest - I had, quite hilariously, not anticipated the significant increase in student messaging from this experiment. Some student self-assessments required follow-up, but the majority did not. Bottom line: I verified students’ self-records, logged in the gradebook that they responded to my request, and for the first time since the pandemic, my midterm grades were submitted a day early.

All this positivity being said, there were a couple of unforeseen issues, as well. About 15% of students messaged me with the, “I think I have a B right now,” and no use of the track sheet was evident. Immediately, I was able to return-message these students with, “Hey, that’s great. You know what would be even better? Let me know what you have completed/passed and what is left to do so we can coordinate that letter grade with what you have accomplished in the course.” In addition, there was a smaller number who never responded. Things were getting better but still had a little ways to go to accomplish my three points of success with high fidelity.

My second full semester utilizing AGS, I used token motivation for students to ascertain both their midterm and final (this was a new addition) grades in the course. The two issues stated above were again present, with a new problem thrown into the mix. Let’s be frank about the end of any given semester: it’s a whirlwind of changing weather, holidays, and catharsis, all at terrifying speed. Asking students to do one more thing, even if it is to determine a final grade, might just be the proverbial straw that breaks their backs. Even with the offer of a token for completing track sheets, participation sunk to about 50% of the class.

Conclusion: A Worthwhile Endeavor

In more recent versions of my courses, I think I have hit a sweet spot. I still begin my courses with an in-depth explanation of why I do AGS and the utility of the track sheet. I mention it as many times as I can, in class meetings and office hours. What’s gone is the token motivation – or perhaps I’ve moved from carrot to stick. I now require students to determine midterm and final grades as distinct assignments in the course that, if submitted after a deadline, require a token to offset. To say I have achieved 100% understanding, participation, and reflection would be false, but with this method, I can get close to 90%, and that is satisfactory for me. Based on my original three goals, many students now track grades day-to-day or week-to-week throughout the term. Not passing or missing assignments/assessment leads to more conversations about improving skill competencies, not grading ramifications. Finally, students no longer ask questions like, “What does my grade look like today?” They state, “I have tracked my grade to an A-, can I confirm that with you?”

A student approached me last year and actually put the course grading model in perfectly simple terms - “In this class, it’s like everyone starts with an A. Non-passed or missed major assessments can reduce that A by full letter grade steps, while minor assessments/assignments not passed or missed lower it by one-third of a letter grade.” I attribute this summation to this student’s attentive use of the course track sheet.

I feel strongly that in Higher Education, it is our job to guide students to understand the world of evidenced-based evaluation so they are engaged in self-reflection, as well as the meaning-making process. Involving students in the determination of their own midterm and final grades is one step in this direction.

Since everyone approaches AGS in their own way, what I have implemented in my course may not work well in yours. Here are some simple steps you can take to do what I’ve described in this post:

Walk students through how grades are determined in your course early and often. Always look for opportunities to remind students that these skills transcend the course you are sharing with them. Repetition is the academic’s best friend.

Have students calculate/determine/reflect on grades at logical points in the term. Best practices dictate doing this when there is the greatest time left for improvement.

Don’t shy away from incentivizing this important exercise. I would rather have my students present at the decision-making table early than spending a whole term trying to figure out the inner workings of the course.

Mio MJ (2024) Alternative grading strategies in organic chemistry: a journey; Front. Educ. 9:1400058. DOI: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1400058

Nilson, L. B. Specifications Grading; Stylus Publishing, 2014.

At Detroit Mercy, we use a homegrown instrument called Student Reflections on Learning.

❤️ it! I went to Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts which is a COMPLETELY narrative evaluation based Liberal Arts College in it's "Divisional" approach to "Faculty Committee-Based" supervision of each student, along with the traditional Academic Advisor that every college student has.

Even the Natural Science program at Hampshire is HEAVILY research, experiment and narrative evaluation based. SO, I very much like what Professor at Detroit Mercy is doing.

The calculation of the current grade was a big challenge when I tested out alternative grading. I had even developed an excel sheet and all they had to do was to put the numbers for eight standards in the highlighted rows. Even then, they complained that they did not know their grade. The CANVAS grade reflected their lowest possible overall grade though at any point in the course - so they were not totally clueless about their grade if they did not wish to mess with the excel sheet.

Blog: https://www.usf.edu/citl/news/2024/multiple-chance-testing-for-equitable-grading.aspx

AI Generated Podcast: https://notebooklm.google.com/notebook/b21952ff-326f-44d3-9f08-b2ea10e2dcfc/audio