The Four Pillars of Alternative Grading

A framework for understanding and using alt-grading, no matter the starting point

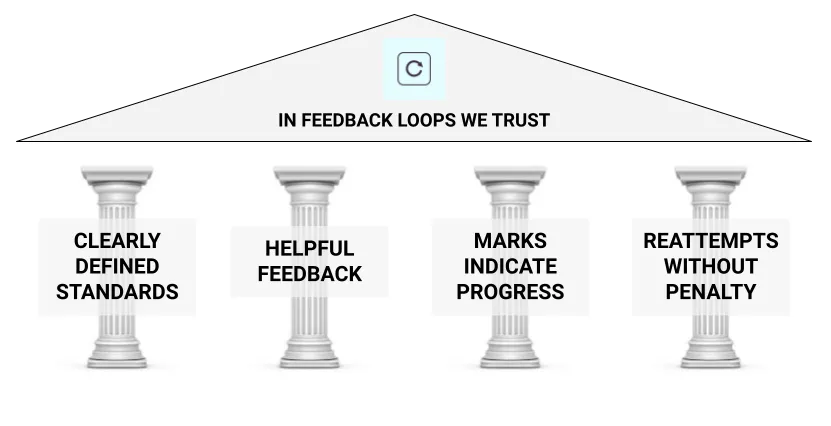

If you’re read more than a handful of posts here, you have no doubt heard about the The Four Pillars of Alternative Grading. It’s a framework that most of these articles, not to mention the Grading For Growth book, are structured around and a constant presence in our content.

But recently, David and I realized that despite this, we had never written an article specifically devoted to this idea. We first proposed The Four Pillars in this article where it is presented as a “beta version” along with a cheesy visual that I made. The visual, somehow, remains stuck at its initial level of cheesiness1. But our understanding of the model, and its importance to how we and other faculty think about and use alternative grading, has grown over time. Today, it feels more like a mature conceptual framework than a “beta”.

Today’s article is intended to be an all-inclusive guide to David’s and my current understanding of this model and how it’s applied to practical teaching situations.

The model and its origins

David and I came up with the Four Pillars model while doing research for the book. We had planned to write a chapter in the book for each of the major forms of alternative grading: one chapter on standards-based grading, another on ungrading, and so on. But when we began to talk with faculty members who were using alternative grading successfully2, what we found, overwhelmingly, is that nobody was using just one form of alternative grading. Instead, people were employing (or inventing) different combinations of approaches, tuned to best serving their students.

This made us change our approach. We started asking: What do all these successful implementations of alternative grading have in common? As described in the article linked above, we found four main commonalities, which we call The Four Pillars of Alternative Grading:

As you can see, we added a “roof” to the pillars: The feedback loop, which all of these pillars support and which I’ve recently stated is instantiated through the concept of deliberate practice3.

The Four Pillars model has been especially helpful, we’ve found, for faculty who might be curious about alternative grading but hesitant to try it because they believe it’s too complicated or time-consuming, or are otherwise hesitant to go all-in. The model boils all functioning alternative grading systems down to four mutually supportive components4, which not only highlight the essential simplicity of alternative grading but which also allows us to encourage these curious faculty by saying: Just pick one pillar and try one thing related to it. You do not have to go all-in with a full course redesign around alternative grading if you don’t want to5 and even just one step along one pillar is both a win for students, and a positive step for you.

Although we’ve done this elsewhere on the blog in the past, let’s dive into each pillar one by one.

Clearly Defined Standards

Having clearly defined standards means: Student work is evaluated using clearly defined and contextually-appropriate criteria for what constitutes acceptable evidence of learning.

This means, among other things:

Students are aware not just of what material is being covered, but the specific actions that they can, or need to, perform in order to demonstrate their mastery of the content to you, on assessments. Those should be actions, framed using action verbs, not as internal states (“Know”, “Appreciate”, etc.). And those standards/actions are made public, given to students before assessments take place (ideally in a syllabus). In other words, we are giving students the target we want them to hit, along with the chance to prepare themselves to hit it, possibly after repeated attempts (see Pillar #4).

Those actions are contextually appropriate, meaning that the targets we ask students to hit match where the course is situated academically. For example, writing a proof of the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic is not contextually appropriate for a College Algebra student, but would be for an Abstract Algebra student.

The reason this pillar is a pillar is that we will be gathering acceptable evidence of learning. You, as the instructor, get to decide what acceptable means in your class6. Note the focus is on evidence of learning, which does not primarily pertain to phenomena that are merely adjacent to learning, such as engagement, professionalism, attendance, and so on.

I would add one other point: Part of being clear means being aligned. It takes more than just being clearly stated for a standard to be clear: It also should be directly aligned with class activities and with assessments. So, a student should not get a nicely-stated standard in the syllabus but which is then never instantiated in class or seen on an assessment — that would send mixed messages about the standard, i.e. it would not be clear.

With clearly defined standards, we are telling students: Here is what you need to know, and here is how you can show me that you know it. The presence of such standards gives students something to organize their efforts around and helps them feel safe taking intellectual risks. So, in some ways, this “pillar” is actually more like a floor or a foundation.

It’s often helpful to understand concepts like this by looking at counterexamples. The opposite of clearly defined standards could look like several things: It could mean no standards whatsoever are given, and students are left on their own to guess what they are supposed to know. Or standards could be given, but they are vague or unobservable, for example, if we ask students to “know” or “appreciate” something7. An unclear standard could be specific and observable, but “double-barreled” in the sense that a single standard is really getting at two different concepts (which isn’t clear). Or, again, a standard can be clearly stated and well-constructed but neglected or ignored in class and on assessments, which sends an unclear message.

David has much more on clearly defined standards and what it means to meet them, in this article.

Helpful Feedback

Helpful feedback means: Students are given actionable feedback that the student can and should use to improve their learning.

In an earlier unpacking of this pillar, I defined “feedback” as evaluative information about the outcome of an event or action that is given back to the source of that event or action. That definition applies generally, including to non-human systems like thermostats or sound systems where (as Jimi Hendrix showed us) the result of an action can be “fed back” into the system to influence the next action.

For the specific context of learning, there’s a little more to it: “feedback” in that sense refers to information provided to a learner about their performance, understanding, or behavior, with the purpose of guiding future improvement. It’s not just inputs and outputs of an impersonal system, but purposeful with a human need in mind. That purpose is “future improvement”, which around here we would just call growth.

What makes feedback helpful?

Helpful feedback tells the whole truth about where the student’s work is situated relative to the clearly defined standards we met in Pillar #1. It provides students with real information, warts and all, about their work. It neither refrains from telling students things they may not like hearing, nor leaves them hopeless by insufficiently highlighting positives.

Helpful feedback, like standards, is clear and has a bias toward action. And it leaves students not only with an accurate picture of their current situation but also simple, practical actions they can take to improve it.

Feedback, in my view, is at its most helpful when it comes from a human voice that has the student’s best interest in mind. It comes from a place of knowledge of the student — their past work, their strengths and weaknesses, and so on — rather than from thinking of the student as just a row in a spreadsheet.

I often describe helpful feedback as feedback that invites students to participate in the next iteration of the feedback loop. I draw upon my own experience as a musician here: When I play a song with one of the bands I belong to, and I get feedback from the audience or a bandmate, the best kind I receive will say truthfully what I was doing well and what I need to work on – not just one or the other, as all-positive feedback just inflates my ego and doesn’t help me iron out my issues, while constant negative feedback shuts me down. And specific actions give me something to do to work on it, which activates the deliberate practice machine and motivates me to do it.

What’s the opposite of helpful feedback? It could mean getting no feedback at all, as many do when they give only marks (that don’t indicate progress, see Pillar #3) with no guidance. Or it could mean feedback that is inscrutable — for example, the way I used to give feedback to students by scrawling half-sentences that were more interjections than guidance (“UNCLEAR”, “HOW?”, etc.), in the margins of their exams. It could mean that the feedback is auditive and backward-looking, for example merely to justify why a certain number of points was taken off. It could also refer to feedback that’s mean-spirited or in some other way shuts students down, as we all are tempted to do at times. And note that both overly negative and overly positive feedback can shut students down.

Marks that Indicate Progress

Giving marks that indicate progress means: If you choose to put a mark on student work, it should serve as a progress indicator toward attaining the clearly defined standard(s) the assessment addresses.

As explained in an earlier article on this pillar, a “mark” refers just to the number, symbol, or string that we might put on student work, like “74” or “Satistactory”8. Importantly, putting a mark on student work at all is not always necessary. This is the basis behind ungrading/collaborative grading: Not marking student work, but just giving feedback, then determining the course grade collaboratively later based on the student’s (unmarked, but thoroughly evaluated) body of work.

Traditional point allocations rarely, if ever, indicate progress toward a standard despite appearances that they do. Point totals merely indicate how many or what proportion of possible points were accumulated on the assignment by the student, but this need not (and often does not) have any reference to a standard. A “point” is not a unit of progress. On points-based assessments, any progress toward a standard must be inferred by the student, who often lacks the perspective to do so (especially if there are not clearly defined standards) and which is hard or impossible in the first place due to the deep and inherent statistical issues with points.

Marks that indicate progress, do so in at least a couple of ways:

They serve as a thumbnail at-a-glance indicator of the quality of a student’s work relative to one or more standards. That means they are brief, simple, and clear and the student can get a broad idea of their progress just by looking at the mark.

At the same, the mark isn’t supposed to replace helpful feedback (Pillar #2) but instead help students interpret it.

An example we’ve used before that is familiar to most faculty is submitting an article to a journal. Journal submissions come back with marks, like “Major Revision Needed”. If there’s no actual feedback on what, exactly, needs to be revised, then the mark isn’t helpful! But with that feedback attached, even from Reviewer 2, the mark makes us curious about, therefore more likely to accept and act on, that feedback.

As before, let’s consider the opposite: What would giving marks that don’t indicate progress look like? It wouldn’t necessarily mean “no marks given at all”! Skilled approaches to ungrading/collaborative grading eschew marks but still support student progress via pure feedback. Mostly, it looks like giving a mark that indicates nothing — for example if I marked student work with one of the four card suits (♥, ♦, ♣, ♠) which look cool, but convey no information (unless I provide a rubric that explains each). Again, points are closer to glyphs like these than they are to measurements; they have the same lack of information content about student progress unless explained in other terms.

Reattempts Without Penalty

The final, and I think most important, pillar is reattempts without penalty, which has been the subject of several posts here (example, example, example). This concept means: Whenever it makes sense, any assessment for which a reattempt would promote student learning, should be allowed a reattempt with no penalties.

It doesn’t always “make sense” to allow a reattempt. For example, in a flipped classroom situation where pre-class work is graded, a reattempt of a pre-class preparation assignment defeats the purpose of the assignment (preparing for a class meeting), even though it might promote learning9. But in situations where reattempts do make sense and promote learning, they should be available, otherwise there is no feedback loop in the course.

Two very important notes are in order here. We’ve made these before at the blog and I’m making them again now:

“Reattempts without penalty” does not mean “reattempts without limits”. Nobody expects a professor to allow unlimited retakes of assignments. We are all human and have lives, and any reattempt policy in a grading system should start from that human consideration and work backwards until the reattempt logistics work. Also, student preparation for reattempts can improve greatly when the reattempts are limited, as David wrote about here. You can, for example, limit reattempts on a quiz to three total; or once per week; or something else that works for you.

“Without penalty” means without penalty. Penalties that are disallowed include outright deduction of points (but, see Pillar #3 for why points themselves are not a great idea) for taking a reattempt, or “soft” penalties like partial refunds of credit. As an example of the latter, I used to give tests graded out of 100 points, then offer a retest, and I would refund half of the difference to the first attempt. (So a 60 on the first attempt followed by an 80 on the second was recorded as a 70, for instance). This sounds nice, and it’s better than nothing, but in reality that’s a penalty. The fourth pillar would say that anything other than recording the higher of the two attempts, is a penalty. And we don’t want to penalize, implicitly or explicitly, the participation in the feedback loop that we seek.

One Pillar, One Thing

As I mentioned earlier, perhaps the best thing about the Four Pillars model that I’ve witnessed is its ability to take a task that feels impossible to many faculty — converting one’s assessment and grading scheme from traditional to alternative — and turn it into a coherent system within which one can take small, consistent steps that accumulate over time. If you are fed up with how grading works, and have read or heard about alternative grading, but feel you don’t have the resources or energy to pull it off, there’s good news: You can do it. Just pick one pillar and do one thing.

If you have never written out clear learning standards for your courses, you can scan ahead to next week’s lessons and write those out using the guidelines David and I and others have written about here. If you don’t have time to do the whole week, just do Monday. Suddenly, you’re taking positive action that can snowball with repetition. Then see what happens.

You might simply work on making your feedback better, whatever that looks like: More truthful — for example don’t be afraid to call out, in a professional way, things a student needs to work on. Or more fully truthful — make a point to say at least one positive thing on each student’s work on the next quiz. Or simply using words instead of half-sentences or points. Try something like that and see what happens.

If you’re up for more of a challenge, change up the marking system you use on the next assessment. Giving a 10-point quiz on Monday? Tell students you’re going to experiment with a new way of doing it: All students will get grades of “Excellent”, “Satisfactory”, or “Unsatisfactory” (or “Retry”, if you want to try the next pillar too) based on clear, thorough verbal descriptions that you provide. One of those three words along with helpful feedback will appear on each paper. “Excellent” grades will be recorded in the gradebook as 10 points; “Satisfactory” as 8; “Unsatisfactory” as 4. See what happens.

Or you could try allowing one reattempt on one small-scale assessment. The 10-point quiz I just mentioned? Mark it using the simplified three-level system (or don’t, since we’re only talking about “one pillar”) and set aside class time the class following when you hand it back, to allow any student unhappy with the result to retake a new version of it — similar but not identical questions, no questions asked, no penalties assessed — then keep the higher of the two scores. See what happens.

Whether you are new to alternative grading, a seasoned pro, or just curious — or skeptical! — about it all, the Four Pillars framework can help demystify the idea and point you in a direction for deeper understanding and practical use in your classes. They continue to guide mine and David’s thinking and hopefully yours as well.

The plan was to get a real graphic designer make something nice for us to use in the book. Then the good folks at Routledge went ahead and put the cheesy version in the manuscript and then it was too late to change things. I’m OK with it. There’s something 1990s-era charming about how it looks.

Some of those conversations turned into the case studies that you will find in the finished book.

And did I mention the graphic is cheesy?

We resisted the temptation to be mathematicians and call this the “Basis for Alternative Grading”, in the vector space sense of the word “basis”. But if you know a little linear algebra, comparing the Four Pillars to a set of basis vectors is highly illuminating: The entire “space” of alternative grading is “spanned” by the pillars, and no single pillar is a “linear combination” of the others. And, each pillar describes a particular dimension or direction along which a person can travel, pedagogically speaking, in their classes.

I would say, fortune favors the bold and it can be easier, psychologically, to go all the way and commit to a wholesale reboot of your grading than it is to do things piecemeal. So I’m not personally a believer in incremental implementations. David disagrees, last time I checked, and we write about both sides of that issue in the book.

Some exceptions apply, for example if your department has its own set of standards that you are expected to use as part of a coordinated cohort of sections.

I loved David’s description of this as “grading on vibes”.

Americans often call this the “grade” but as explained in the linked article, this term is ambiguous.

I recommend that pre-class assignments for flipped instruction not be graded on the basis of correctness, but on completeness and effort only, or not at all.

Another great post. I hope you will also think about looking at time differently because of the incredible impact the arbitrary march through the curriculum has on students. IF the standards and expectations are clearly defined, then why does the teacher need to be in control of the timing of student learning? This could also help a great deal with the reassess issue -- one of my 3 guiding principles (my version of your pillars) is "Never put a learner in a situation where they are not ready to be successful." So why take time for an assessment when the learner (and probably teacher) know ahead of time that they won't be successful meeting the standard(s). There are ways to do this that can work inside existing models, as the FILL approach that I often write about, demonstrates.