Small Alternative Grading

You can use alternative grading in your class tomorrow

A concern that I hear frequently about alternative grading is the amount of work required to completely change a class’s grading system. It takes a lot of time and energy to revamp everything.

Good news: You don’t have to completely blow up your whole assessment system to make a difference. So today, in the spirit of James Lang’s classic book Small Teaching, here are some “small grading” ideas: concrete ways to bring impactful elements of alternative grading into your classes right away – even tomorrow! – without completely reworking your grading system.

The Four Pillars of Alternative Grading help us focus on what’s effective in an alternative grading system. I’ll organize these “small grading” ideas around these pillars.

Reassessment Without Penalty

I’m going to start with our fourth pillar, reassessment without penalty, because it provides some of the most immediate and impactful ways to implement alternative grading.

Simply put, allow students to reassess one specific assignment and completely replace the original grade with the new one. That’s it – you can do this tomorrow!

Here’s a bit more concrete advice about how to do this:

First, choose one assignment to reassess. You can probably think of one quickly: Did students struggle with a recent exam? Would they benefit from reviewing the topic of that last essay? Pick an assignment where students will see a lot of value in a reassessment. You can also limit the amount of work involved and give students more agency by, for example, having them choose one page or problem from an exam to revise.

Next, choose between a new attempt and a revision:

New attempts work best with quizzes, exams, or other assessments focused on discrete skills. This also means you’ll need to write a new version of the assessment, or perhaps just rewrite a few of the most important questions where students struggled.

Revisions work well with essays, projects, and other larger assessments that involve higher-order reasoning, synthesis, “putting it all together”.

Then, structure metacognition and include a reflective cover sheet. Helping students think about their thinking – metacognition – is a critical part of enabling a feedback loop. Help students do this by asking them to respond to a few short questions. For example, you can use one of these (depending on the type of reassessment):

What is the most important thing you learned while completing this revision?

Describe some specific resources you used to improve your understanding, and how they helped you.

Fill in the blanks and be as specific as possible: I made a mistake on ___. I did not understand ___. Now I know ___. To show my improved understanding, I ___.

If students need to give you any other data (such as if have a choice of questions to reattempt), put that on the cover sheet too. You might also give instructions to review specific resources, attempt an ungraded practice problem, come by an office hour to discuss important points, or attach their previous work for comparison.

Finally, tell students about it! Emphasize what they need to do (the logistics) and why you’re doing it (the benefits, for them). Consider reducing the amount of work that’s due while the reassessment is “live” so that students don’t see it as just another thing on top of their normal workload.

This process will work even better if you’ve given helpful feedback on the assignment (see later in this post for a bit of advice on that).

When reassessments come in, grade them as usual, and replace the old grade with the new one. This is key: Averaging is the source of many of the biggest problems with traditional grading. Reassessments let students show you what they’ve learned, so make sure that you value that fully and don’t penalize them for needing to engage in a feedback loop.

Marks that Indicate Progress

Continuing our backward tour through the four pillars, pick one assignment and change your grading scale to use marks that indicate progress such as “Satisfactory / Progressing / Not Yet”.

The benefits are twofold: For you, having a coarser scale makes your grading easier, faster, and more consistent. For students, the marks themselves give more meaningful feedback, especially if they’re paired with an actionable next step (such as an opportunity to reassess).

Here’s a simple way to do it: Rather than adding or subtracting points for doing (or not doing) specific things, instead write out a short definition for each number of points. Then grade based only which definition a student’s work most closely matches. Write the definitions in clear and understandable terms, and share them with students

Here’s a rubric you can use for a question worth 3 points:

Satisfactory (3 points): Fundamentally correct. Demonstrates clear understanding of the topic with no important errors.

Progressing (2 points): One important error related to the topic, or so many minor errors that they call understanding into question.

Not yet (1 point): Uses an inappropriate method; or multiple serious errors related to the topic.

Unassessable (0 points): Not attempted, or work that is irrelevant or can’t be understood.

(These definitions work best if the “topic” is very clear to you and to students – for example, if you’ve included clearly defined standards on the assignment.)

Make sure you really are using these definitions when grading. Avoid the temptation to add or take off points, and instead focus on selecting a mark based on how well it matches the student’s work.

Avoid insisting on perfection: “Satisfactory” intentionally allows for unimportant errors – always ask yourself if an error shows evidence of misunderstanding, or if it’s irrelevant to the topic at hand. (For more information, see: What does it mean to meet a standard?) You might discover yourself making different choices in how you grade some responses, as you think about whether work is “fundamentally correct.”

You could scale these up to higher point values, but I’d suggest limiting yourself to 3 or 4 points instead. This avoids the temptation to adjust points up or down a bit (is that really an important error?) thus ignoring the definitions you wrote. Focus on the meaning instead.

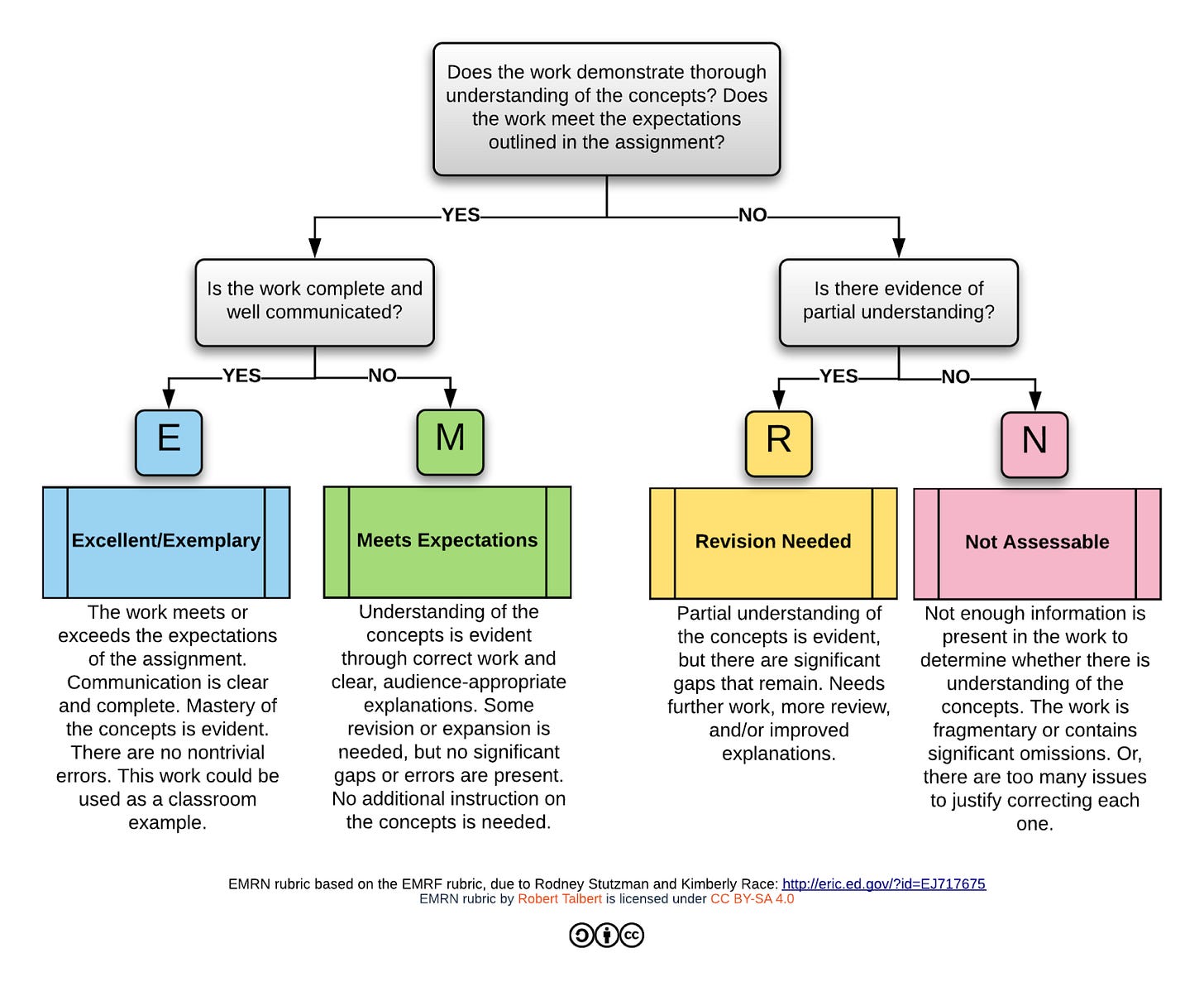

You could also use a pre-made rubric like Stutzman and Race’s EMRF rubric or one of its many variants, such this EMRN rubric from Robert’s website:

The biggest benefit of a multipurpose rubric is that you can reuse it on many different types of questions. The EMRF rubric and its variants also allow you to recognize excellence in communication that goes above and beyond correct work.1 You could translate the mark into points like above – again, keep the number of points small. I’d suggest treating “Excellent” as a bonus point, allowing “Meets Expectations” to earn full credit. After all, if a student meets the expectations you’ve written, why would that be worth less than full credit? Plus, if you’re going to have “bonus points” at all, what better way to use them than to recognize excellent evidence of learning?

Taking a bigger step, you could decide to record only satisfactory marks (as 100%), but give feedback and ask students to reassess unsatisfactory ones until they are satisfactory. This approach works well with larger assignments like drafts of essays that benefit from revision. Be sure that students understand that they don’t have a grade at all until they’ve reached “satisfactory”.

Helpful Feedback

You’re likely leaving feedback for students already. My advice here is simple: Take a bit more time to make sure your feedback is helpful. Changing your feedback to be more actionable and focused on specific ways to grow can make a difference on its own.

Some more concrete ways to do this:

Pick one assignment, or even one important part of an assignment, and focus on giving helpful feedback only on that.2 Then set aside time in class for students to review the feedback and talk with each other about it. As with reassessments, it helps to give structure to this discussion. For example, have students individually read feedback for 5 minutes and think about it (or even make this a pre-class prep assignment). Then, in pairs or groups, have students identify common feedback they received and brainstorm how to address it. If you had a few major types of feedback, have students group up with others who had the same main issues. Or, have students help each other make sense of feedback that they didn’t understand. You can circulate or take questions afterwards, to address the most common or pressing questions that were raised.

To save yourself time and to reach the students who most need helpful feedback, you could implement a tiered feedback approach (like this one described by Lindsay Masland): Give basic feedback to all students using a short rubric — you could attach the rubric to the assignment with common feedback items pre-filled and circled, or copy-paste feedback into your LMS. Make it clear that any student can ask for more detailed feedback, then do so for those students who ask. If a student says that they don’t understand this feedback, set up an office hour meeting to give them feedback interactively.

In every case, give students specific advice about where students can put this feedback into action in the future. Or, pair feedback with the opportunity to revise one assignment, as described earlier, and you’ll give students a big incentive to make good use of your feedback.

Clearly Defined Standards

Finally, what about standards? “Standards” can range from short statements describing an action that students can take to provide evidence of learning (“I can evaluate derivatives using the limit definition”) to longer, detailed lists of important qualities for their work, also called specifications.

There are many ways to use standards in even a traditionally graded class:

Tell students what they’re working on. Pick one upcoming class or assignment and write up a few clear, fine-grained standards that apply to it. Share them with students (in class, or on the assignment) to help them better understand what skills they’re practicing.3

Align your assignments. Take 15 minutes to write out a rough list of the most important topics in the remaining sessions of your class (aim for 5–10 at most). Then run through your list of assignments and quickly identify which topics each one addresses. Sit back and take a look: Do you assess everything you said was important? Does every assessment address an important topic? Is what you assess heavily weighted towards two or three topics, at the cost of others? You might be surprised at what you see, all in at most 30 minutes. Then use that information to adjust the focus of your next big assessment. Even if you never share this information with students, you can improve the overall structure and focus of your assignments.

Make specifications and use them for grading. Rework your rubric for a larger assignment (like an essay, project, or presentation) into a set of specifications. Write out a detailed description of what a “successful submission” should include. This could even take the form of a checklist. Don’t think about this as instructions, rather, focus on describing the qualities that the result should have. Then go back over it and ask about each individual item: Should the student fail this assignment if they don’t do this? If the answer is “no”, cut it out of the specifications or refocus it (for example, “Margins are 1 inch” is not worth a failing grade; but “Clearly states the central argument of the text” probably does matter that much). You could share these specifications with students as part of the instructions, and even turn it into a rubric for grading the assignment (using marks that indicate progress – see above!).

What’s next?

If you are interested in alternative grading but haven’t taken the plunge yet, I hope you’ll use one of the “small alternative grading” ideas here tomorrow. Literally, tomorrow! Pick something that makes sense and see how it works for you.

One important bit of advice: Do not tell students you’re “just trying this” or “we’ll see how it works”. That tends to undercut its effectiveness, and nobody likes to feel like they’re being experimented on. If you’re going to make one of these small changes, be sure you believe in it, and present your reasons clearly in student-centered terms.

If you like the results, incorporate that idea into a future class from the beginning. Expand it to encompass more assignments.

For example, in a future class, you could offer reassessments for one type of assignment. Or you could incorporate a token system that allows students to reassess any assignment they like, but limited by the number of tokens. Alternatively, create a list of standards before the start of the semester, and use that information to make sure your assignments thoroughly cover the most important topics without missing anything, or being unduly weighted towards a “favorite” topic. Rework your grading scale so that it’s entirely based on clearly defined marks rather than an accumulation of +1’s and -½’s. Or go all out – use specifications, feedback, marks, and revisions – but only on one major project or paper.

There’s no requirement to go “full out” with alternative grading, and even a small change in a class can make a big difference. Plus, experimenting with small changes can give you confidence to use them in a bigger way. Give it a try, tomorrow!

Think carefully about what “excellence” in communication means — are you unduly giving a benefit to students who come from a certain background, or have prior experience, rather than those who show their thinking in especially clear or thorough ways?

“Helpful” feedback does not necessarily mean a lot of feedback. Be targeted, specific, and focus on actionable followup steps. Don’t overwhelm students with paragraphs of text.

Worried about “giving away the answer” by telling students what they’re doing? Here’s one of my favorite standards: “I can choose an appropriate method to evaluate an integral, explain my choice, and use it correctly.”

Your advice isn't just for teachers starting out. I found "set aside time in class for students to review the feedback and talk with each other about it." especially helpful. Thanks!

Excellent ! Easy to implement 😊