My go-to alternative grading templates

Where I begin when I'm designing a new class

There’s no one right way to use alternative grading, and my approaches are tailored to my situation (math at a large public regionally comprehensive university, with small 20-30 student sections, and no TAs). Over the years, I’ve developed two specific approaches to alternative grading that work well for me. Whenever I teach a new class, I begin with one of these “templates” and modify it to fit that class.

I think that these templates could be helpful to many others, so today I’m sharing them with you.

In our book, we advise readers to think about the main focus of their class: Is it more about content and skills, concepts and general processes, or a mix? Each option works better with different types of alternative grading. My two main approaches are based on this same choice. Let’s take a look at two templates: one for more skills-based classes, and one for more conceptual classes.

Skills-based classes: quizzes and advanced homework

Some classes I teach are more focused on individual skills and specific content. These are usually introductory classes like Calculus, which are also prerequisites for other classes.

In these classes, I use regularly scheduled quizzes or exams to assess discrete skills. Separately, I assign “advanced homework” to encourage synthesis and develop communication skills. Final grades are determined by completing a list of criteria related to the quizzes, homework, and engagement. Here’s how each of these elements work in terms of the Four Pillars of alternative grading.

Skill quizzes with standards: To test students on individual skills, I use regularly scheduled quizzes or exams and assess students on each skill separately. This is an example of Standards-Based Grading.

Clearly defined standards: I create a list of 12-15 standards (about one per week in our 14 week semester). Depending on the frequency of assessment, each quiz or exam includes questions covering 2–4 new standards, plus new attempts at a selection of previous ones.

Helpful feedback: Students upload all work to our LMS (Blackboard), where I give them feedback. That lets both the student and me have ready access to the feedback for reference and studying.

Marks that indicate progress: I use a 3-level rubric to assign a mark for each standard, based on a student’s work on the relevant questions on a quiz. Successful means what it sounds like. Needs New Attempt indicates a significant error, so that students need to make a new attempt to answer new questions on a future quiz.1 The third option, Revisable, is the most interesting. When a student’s response leaves some question in my mind, perhaps an ambiguity or a minor omission, I assign this mark and give them these instructions: “You can revise this by coming to an office hour and explaining: (1) What went wrong, and (2) how to fix it. If you convince me, you'll earn Successful on this standard!” This makes for quick and easy fixes in many cases, and when students are confused, I can pivot to tutoring them.

Reassessment without penalty: Each standard appears on about 3 quizzes or exams per semester, each time with new questions. A student’s goal is to earn Successful on each standard, regardless of how many attempts it takes.2 I create a detailed schedule of which standards will appear on each assessment and publicize it, generally with 3 opportunities during the semester and one more on a final exam. This helps both students and me know what to expect, and spreads out the workload.

The final exam and core standards: Generally, the final exam in this kind of class serves as one last chance to earn Successful on any standards. But in addition, I mark a few of our standards as “core standards” that students are required to attempt on the final exam, whether they’ve previously completed them or not. These cover the most critical topics in the class and serve as a final “recertification” (to use Robert’s word) that the student has retained that knowledge. A student’s number of Successful earned on the core standards on the final exam adjusts their final grade with a plus or minus – see more about this below.

Advanced homework with specifications: These assignments ask students to synthesize multiple ideas, put them together in more interesting contexts, and communicate their understanding in writing. I typically assign one or two “advanced homework” problems at a time, due one week later.

Clearly defined standards: I use a short list of specifications that describe the qualities of a successful submission, which can be scaled up or down depending on the needs of the class. Examples include “Provide a careful statement of each problem, including the problem number”, “Include at least one sentence in each part of your response” and “Use correct mathematical notation as demonstrated in class and the textbook.” One specification is always “Include correct reasoning and justification.”

Helpful feedback: Like quizzes, I give feedback directly through our LMS, in terms of the specifications.

Marks that indicate progress: Each advanced homework earns one overall mark: Successful, Revisable, or Insufficient/Incomplete. Successful indicates thoroughly meeting all specifications. Revisable allows a revision “for free” (see below) even if the work has significant errors, while Insufficient/Incomplete indicates such lack of effort or missing work that students need to use a token to unlock reassessment. This encourages students to make a genuine attempt on their original submission.

Reassessment without penalty: Students can revise and resubmit advanced homeworks along with a reflection about what they learned during the revision. I re-read and re-grade these revisions and replace their previous mark with a new one. I assign homeworks every two weeks, and students can submit one revision of any previous homework that earned Revisable in the week between new homeworks. This limit keeps students focused and limits the amount of additional work and grading. Students can also use a token to either revise an Insufficient/Incomplete homework, or revise an additional homework problem.

Engagement points: For day-to-day practice and other things that I want to encourage, but which don’t need a grade, I use engagement points. I typically use these for pre-class prep work (my classes are usually flipped), traditional practice homework problems, filling out an occasional survey, etc. There are two keys to engagement points: First, they are assigned purely for completing assignments with reasonable effort, not for correctness. Second, there are lots of engagement points available, many more than any student needs to earn an A, which gives many paths to meet those requirements.

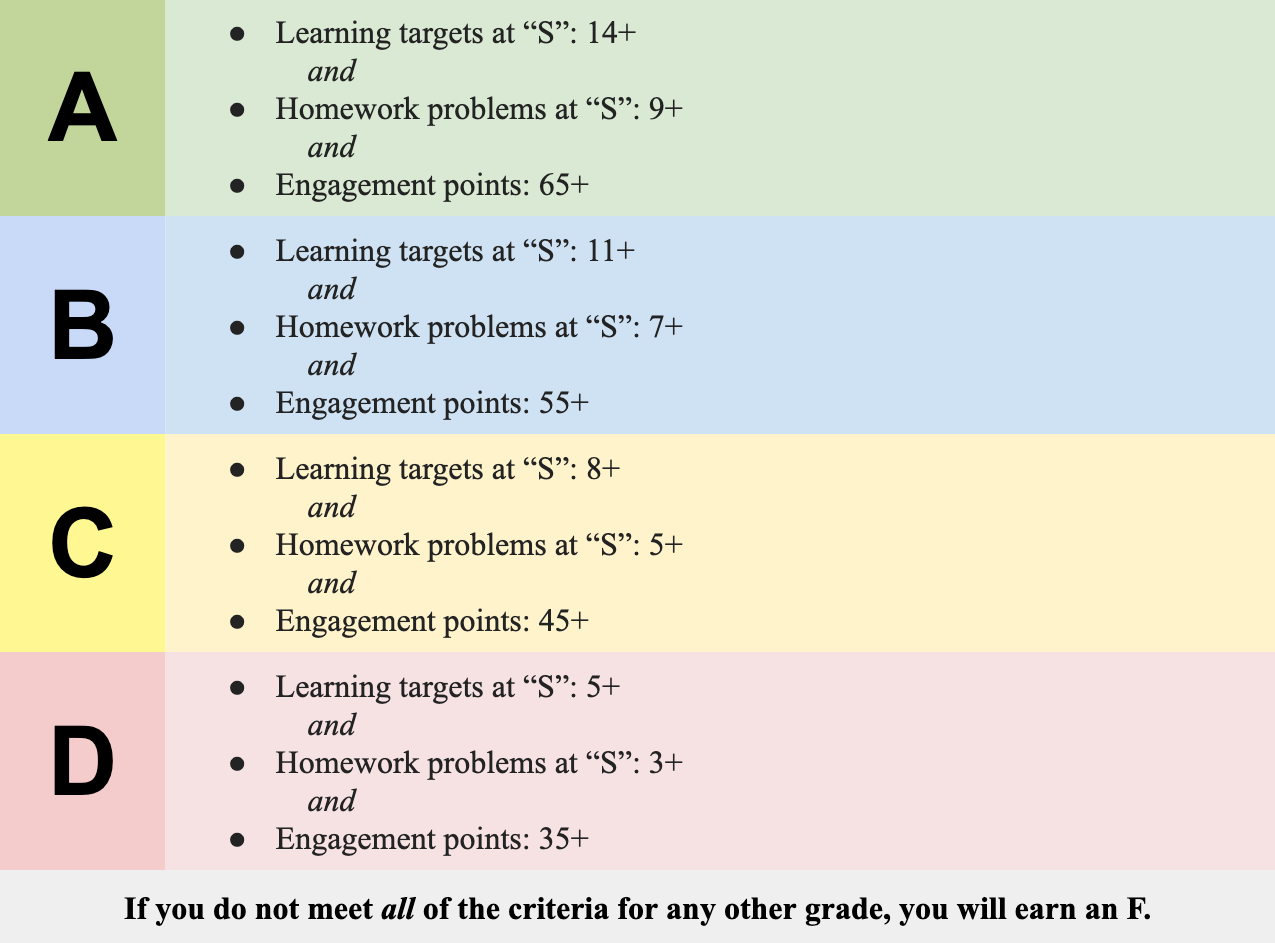

Final grades: Final grades are set by meeting a list of requirements, all of which must be completed to earn a given grade. This is often called a “grade grid”, and here’s mine (note that I decided to call my standards “learning targets” in this particular class):

I also include an explanation of how core standards on the final exam adjust the final grade. A typical example for a class with 5 core standards, based on the final exam:

5 Successful: Add a “plus” to your final grade, e.g. B → B+

3–4 Successful: No change to your final grade

1–2 Successful: Drop your final grade by a “minus”, e.g. B → B-

0 Successful: Drop your final grade by one full letter grade, e.g. B → C.

I’ve found that this approach works well for introductory, primarily skills-based classes. There are many ways to tweak it: Change the number of times a student must earn Successful on each standard, adjust the specifications for homework, or even drop advanced homeworks entirely (although I think that practice with communication is important at all levels). Feel free to use this if it speaks to you!

Conceptual classes: Problem sets with a portfolio

When I teach upper-level classes, the emphasis is usually on mathematical proof, which is fundamentally about logic and communication. These highly conceptual classes are focused on writing and revision.

Homework problem sets: My main assignments are regularly scheduled problem sets, typically 2-3 problems due every two weeks. By “homework” I don’t mean practice, rather, these are large and significant problems that need to be taken home and worked on for a long time. My fundamental structure for these is based on Specifications Grading.

Clearly defined standards: I provide a list of specifications for the overall quality of written proofs. Sometimes these are quite detailed, other times they are brief. I also provide more specific specifications for each individual problem, usually called “Areas for focus”. These emphasize details and skills that students should attend to in that particular problem. If the reason I assigned a certain problem is to practice (for example) applying a certain method, I call that out explicitly in the areas for focus.

Helpful feedback: I give detailed feedback via our LMS. I usually do this in two phases: First, I note important details directly on the submitted document via annotation tools. Second, I give an overall summary and big picture notes in a text field. I try not to overwhelm students with the amount of feedback, so I emphasize that I only point out the most important items – both positive and negative. Students can ask for “level 2” feedback if the want all the details.

Marks that indicate progress: I use a simple scale: Exemplary, Successful, or Not yet. Both Exemplary and Successful indicate logical correctness and sufficiently clear writing, but Exemplary additionally means that the proof (or other written work) is especially notable in some way: exceptionally clear and concise, uses an elegant or interesting approach, etc. Note that unlike my introductory classes, I use multiple levels of “successful” to encourage excellence in writing, and I have only one level that doesn’t meet specifications. This difference, and the ways it’s reflected in the final grades (below), reflect the different level of both expectations and maturity of the students.

Reassessments without penalty: Much like the Advanced Homeworks described above, these problem sets are assigned every two weeks. The weeks between homework weeks are “revision weeks”, in which students can submit a revision of any one previously assigned problem along with a reflection. I give detailed feedback and an updated mark that completely replaces the original mark.

Homework is typically the only kind of assignment in these classes. In-class exams don’t really make sense for classes focused on long-form mathematical arguments.

Final grades via narrative descriptions and a portfolio: I write narrative descriptions for final grades, sometimes more or less specific depending on the class. These descriptions include performance on homework, as well as general engagement with the class and any other items that I’ve decided to include. For example, here’s one from a 400-level proof-based class that I taught last semester:

(In this class, I had added another category – mastery exams – in which students showed me they could reconstruct a few key logical arguments without reference resources. They could attempt each exam multiple times, knowing the questions ahead of time. Students earned “titles” as they completed them: Novice, Adept, Conversant, and finally Enlightened. This is a new idea I’ve been experimenting with, and I think I like it – it might become a standard part of this template soon.)

Students submit a final portfolio that includes an argument in favor of a specific grade, a nod to collaborative grading. The support their argument by including artifacts that they are proud of. These can be homework problems or any other work done for class.3 This is also a chance to explain special circumstances, argue in favor of additional criteria, and show off their very best work. Here’s how I describe the key part of the portfolio:

If you added a “+” or “-” to your grade, if your work didn’t fit exactly into one grade category, or if you would like to argue in favor of a different grade than the syllabus requirements indicate, make your argument here. Be brief, clear, and focused. Explain your reasoning. Cite specific evidence whenever possible (including artifacts). Make the best case you can! If you are happy with your syllabus grade, just say “I’m good, thanks” (or maybe something more witty).4

There’s no one right way to do it

I’ve been writing that a lot lately, and I mean it. If these templates speak to you, feel free to use them and modify them to suit your situation. If you do, please let me know – I love hearing about what works for you! If not, we have tons of case studies in our book and on the blog (here are a few recent examples, but there are lots more!) to inspire you as well.

The approaches I’ve outlined here have evolved enormously from my original attempts at alternative grading, and they now include almost no original ideas whatsoever. Anything that you like in my approaches has probably been stolen lovingly borrowed from my colleagues and collaborators, most especially my coauthor Robert Talbert as well as Sharona Krinsky, and Kate Owens. The four of us just happen to be the original organizers for the Grading Conference, which has also provided a great deal of inspiration to me over the years.

The details of what leads to Successful vs. Needs New Attempt – in particular, what level of error is acceptable and what makes a “significant” error – vary depending on the class. Here’s some advice: What does it mean to meet a standard?

I sometimes require students to complete standards twice to earn credit; this ensures they’ve maintained their knowledge across some span of time. It also creates more grading and bigger quizzes.

I emphasize that students can and should include artifacts that I don’t normally see, such as scratch work, out of class teamwork on a whiteboard, etc. Students do this, and it’s incredibly helpful to see these sorts of evidence of learning that would otherwise be completely invisible to me.

How many students write “Something more witty”? A lot.

Thank you for the post! Having more concrete details helps me to understand how this can work. I don't think I'm still quite ready to jump in the pool, but hopefully I can start dipping my toes in.

Thank you for the great very useful post, David! I see that especially in the second format you rely quite a bit on homework. But what about ChatGPT? I think because of that homework’s stopped being reliable if they contribute to a grade. Many sources say that cheating is massive. What do you think and how you go about it?