How to write clearly defined standards, revisited

Some perspective and a flowchart on this tricky and important process

Having clearly defined standards is the first of the Four Pillars of Alternative Grading, and in my view it’s the “floor” on which the other pillars stand. We’ve written a lot about standards (and standards based grading, and how standards are different from specifications, etc.) here and in the book. But I’m preparing for a workshop I’m giving next month on writing standards, and it’s highlighted some new perspectives on this process that I’ve gained since I wrote this article on “How to write standards” almost four years ago.

Today’s article is both a beta version of that workshop and something that I hope is useful to everyone, as we think about setting up our courses for the upcoming semester.

First, a review

Let’s recap a few things that have been said here before, starting with the definition of a “standard”.

A standard is a clear and observable description of an action that a student can take to demonstrate their learning of some specific topic. Students take our classes (presumably) because they want to learn things. The way we instructors tell whether or not this has happened is to have students do something that produces evidence of learning, which we then evaluate (and sometimes grade). A standard is just a clear description of what that action looks like1.

I like to think of each assessment we give, as a mini scientific experiment in which the null hypothesis is, “The student didn’t learn the topic(s) that the assessment addresses”. The purpose of the assessment is to gather enough data to determine whether to reject that null hypothesis. A standard is the specific operational definition we use in the experiment, for some topic on that assessment.

In my original post on writing standards, I go into some depth on what each of the words (like “clear” and “action”) in the formulation above means. But there is one change that I’ve made: Replacing the word “measurable” with “observable”. Not every item of evidence of learning can be easily measured, or even measured at all in any statistically meaningful way. But in any case a standard refers to an evidence-producing action whose outcome can be observed. We insist on this, because feedback loops — the very heart of alternative grading — are predicated on observations of the outcomes of actions2.

That’s what I mean by a “standard”, but I should also mention what I don’t mean. A high-level learning outcome meant to apply to an entire course, is not (necessarily) what we’re calling a standard. Nor is it a micro-level topic or idea that you might encounter one day in class, but which is never assessed on its own. In past discussions of standards we have called the former course-level objectives and the latter lesson-level objectives. What we mean by “standards” lives in the middle of these — learning outcomes that are high-enough level to capture student learning on important concepts or groups of concepts, yet low-enough level to be specific and observable. These are the outcomes we actually assess, so we called them assessment-level objectives.

So when we talk about “clearly defined standards”, we are not talking about course-wide objectives in a syllabus, such as “Students will practice effective communication” in the syllabus for an English class. This objective is fine as an aspiration, but it’s too vague to be a standard. Nor do we mean something at the atomic scale like “Students will use semicolons properly”, because while this is a good thing to know (and which aligns with the above course-level objective), it’s way too small to merit its own assessment. An assessment-level objective that addresses the former while including the latter might be: Students will write sentences that use correct grammar and punctuation.

A workflow for writing standards

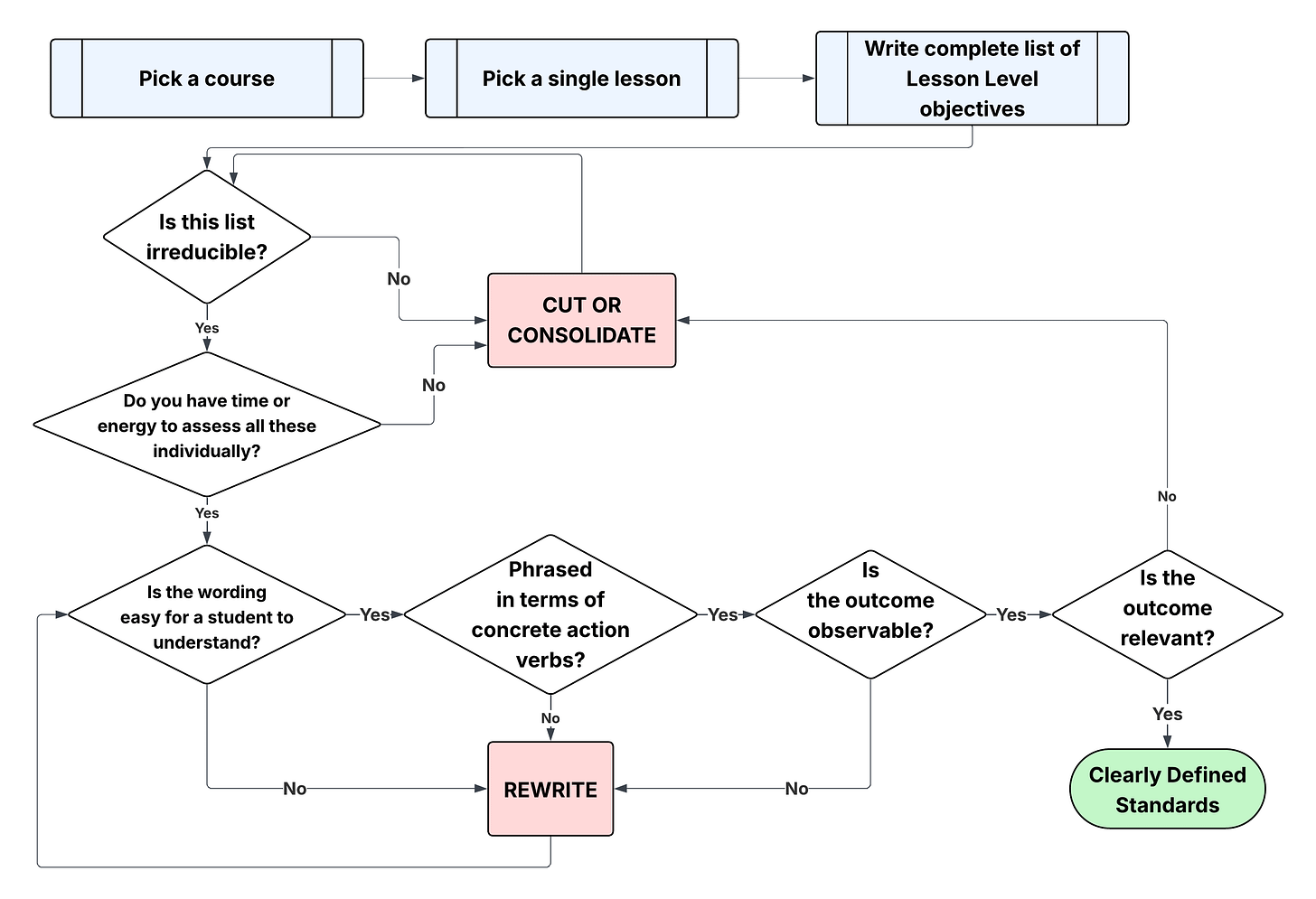

So how do we actually write clear standards? Again, I wrote an entire article about this almost four years ago. But as I was preparing for my workshop, I came up with this flowchart:

This process outlines the exercise I’m having faculty do at this workshop, and it’s my own practice as well. I invite you to test-drive it as you are building your courses for next semester.

The goal here is to craft a list of standards (assessment-level objectives) for a single instructional unit — a lesson, module, week, whatever makes sense for you. So the first row is clear enough: Pick which course and which unit you want to work on. Then, go through that unit and write down an exhaustive list of every idea and topic students will encounter in it, phrased as a learning outcome in a complete sentence (so, not just “Semicolons” but something like “I can use semicolons in a sentence” or “I can explain when to use and when not to use a semicolon”) and don’t worry about how micro-scale it might seem. This might result in a long list. Don’t worry: The process we’re about to walk through is intended to cut that list down to size. If you’re doing this for a whole course, you’d loop through this process for each unit.

Is it irreducible?

The first question to ask of your list of lesson-level objectives is: Is the list irreducible? What I mean by that is: Is the list as short as it can possibly be? Or, are there items on the list that can either be cut, because they don’t need to be included at all; or which can be consolidated with other items, because the item is too small to merit assessing it on its own? If not, i.e. you can cut or consolidate, then reduce. Otherwise, move on.

For example, your initial list might contain the three items (among others):

I can use semicolons correctly

I can use apostrophes correctly

I can explain the history of the semicolon3

If this were my class, I definitely wouldn’t want to have one battery of assessments (an initial one plus reassessments) on semicolons and another on apostrophes. Taken individually, they just don’t rise to the level of importance to merit their own assessments, and it will create a lot more grading than I want. It makes more sense to take all such outcomes about punctuation and glue them together into a single outcome, something like I can use punctuation correctly, and then have a single assessment on that4. That’s consolidation, and it’s likely you will do a lot of this during this process.

As for the history of the semicolon, well, I might find that to be a fascinating subject but I would have to ask myself: Is it really essential for this course, especially based on the course-level objectives? If the course-level objectives spell out (haha) that the history of punctuation marks is a key learning outcome, then leave it in. Otherwise (for example, most introductory writing courses) it’s probably not relevant, despite how cool the topic may or may not be. So cut it if that’s the case. You will likely find yourself doing a lot of that, too.

Coming out of that diamond, you have a list that has been tailored. Now you have to approach it as a human being and ask: If I were to give assessments, each of which targets one item on the list, and each of which might need repeated attempts: Can I handle the workload of creating and grading all those assessents along with everything else? If you honestly do, then proceed. Otherwise, go back and try to cut/consolidate some more5.

These two diamonds are the hardest part of writing standards because they require honesty, and honesty requires courage. Experience feeds both. The first time I tried alternative grading, I had neither. I came up with a list of standards that was 63 items long, each of which required three successful assessments until Mastery was achieved. And I had 60 students. I did not cut or consolidate, because I was certain that every item, no matter how tiny, was of the utmost importance and needed its own assessments. And because it was this time of the year (mid-December) I was rested and removed from the pressures of the semester and so I thought “No problem, I’ll be able to handle all that grading.” The results were pretty much what you would expect. Had I simply been honest with myself about all this, I might have seen the sun once or twice in that semester, rather than be stuck grading day and night.

So I implore you: Be honest with yourself about what truly matters in your course and ruthlessly simplify your lists. And be honest with yourself about what you can and cannot do as a whole person in terms of carrying out the work of grading these standards. Simplify, then simplify some more.

Is it clear?

Next: Is the wording easy for a student to understand? What this means is: If the student knows all the terminology in your standard at an acceptable level, will they know what to do to demonstrate their knowledge, just by reading the standard?

Obviously, students have to learn the terminology in the standard. If a student doesn’t know what a semicolon is, they can hardly be expected to demonstrate they can use one. But assuming they do know, the rest of the action should be easy to parse: I can use a semicolon correctly in a sentence, as opposed to something like I can employ proper usage of a semicolon which says the same thing but the language could be simpler, or I am totally good with using a semicolon which (in addition to being cringey) doesn’t really specify an action to perform. What will a student do to show you that they are “totally good” with it? The answer to that question is the real standard.

Sometimes knowledge of terminology is itself the standard. For example a standard in one of my classes is: I can determine if a relation is reflexive, symmetric, transitive, or antisymmetric. The term “relation” is something students will have learned previously in class, but the other four technical terms are the subject of this standard. Here, we have to look inward to decide what we want from students. In this case, I want students to show me understanding of these four terms. But what does that “understanding” look like? I could have said, I can state the definitions of… those terms and that wouldn’t be out of line. But in my classes, I want more than just memorization, so I ask my students not to recite the definition but apply it to a concrete situation.

And how will a student know how to do this? I think the key is practicing the standard in class. On the day that we discuss these four properties, the class meeting revolves around reviewing the definitions and then spending the middle ½ to ⅔ of the class with students working together to “determine” whether various specific relations have those properties. In other words, we’re using the class meeting to engage in deliberate practice, and the practice session shows the students what the standard means6.

The next diamond (Is it phrased using an action verb?) is just a byproduct of the above. A standard, as we’ve seen, is an evidence-producing action. What action is it? You determine this, and then make sure that action appears in the standard.

Does it pass a final reality check?

The last filter or diamond I have in the flow chart is: Is the outcome relevant? Now that my objective is optimized and clear — does it matter?

If you feel like we’ve asked this question already, you’re right. In the first two diamonds, we were given an opportunity to engage in addition by subtraction — removing the inessentials, combining tiny objectives into one Voltron-like objective that could be assessed without micromanaging, and further simplification if the list was still too long for us to commit to. But sometimes the need for simplification isn’t fully evident until we actually clarify the standards. By going through the process of clarifying a standard, we may discover it’s not really that important after all.

So this final diamond in the chart, is us asking ourselves: Are we sure we’ve simplified as much as possible? You have until the first day of classes to make changes to this list of standards. After that point, every item on that list is a commitment you are making to assess that item, possibly multiple times, multiplied by the number of students you have, multiplied by the number of minutes it will take to grade each attempt. This is your last chance to be fully honest with yourself about that list.

I would encourage you to subtract as much as possible from your course until what you have left standing is a minimalist monument to the essential ideas of whatever it is you’re teaching. Like a stack of Jenga blocks near the end of the game, it’s still standing, but taking one more block out will cause a collapse. We can be really bad at estimating what’s actually essential. So I would encourage you now, before the semester starts, to just remove as much stuff as possible and think about how the course would play out. You might be surprised at what you can get away with.

Conclusion

There’s no science to any of this. It’s a craft, and it’s the result of we instructors engaging in the very feedback loops we want students to encounter — an iterative trial and error process to arrive at some version of this flowchart that really works for us individuals on a semester to semester basis.

I’d love to hear some of your variations or corrections to this process in the comments!

Standards can go by different names: objectives, outcomes, targets, goals, etc. There can be some confusion here. For example, a college might have certain “learning outcomes” for its general education courses, but these might not be standards in our sense; at the same time, a general education course at that college might have “learning outcomes” that are standards in our sense. Sometimes people ask what the difference is, between standards and objectives and outcomes and all the rest. There’s no definitive answer. Whatever name one uses, the definition here is what it means.

This is assuming the truth of the statement: If a student demonstrates sufficient evidence of learning, then they have actually learned. This is my belief, but there are a number of good-faith objections to it. For example, one might argue that the equivalent statement “If a student has not learned, they will not demonstrate evidence” is false, because sometimes students demonstrate evidence without learning — they have a lucky guess on an objective quiz, or they use generative AI excessively, etc. Or, one can argue that an assessment does not result in evidence of learning but in evidence of the student’s ability to express what they know, so for example a student with poor English skills might have learned but lacks the tools to demonstrate it, therefore one can’t conclude anything about learning from an insufficient demonstration. There are other challenges to this claim, and I’ll need another post to get into all those sufficiently.

In case you’re interested: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2019/08/01/the-birth-of-the-semicolon/

Would you accept the outcome of this assessment if, for example, students aced the use of punctuation on everything but semicolons? If not, does this mean we should really have separate assessments for each punctuation mark? That’s a question only you can answer, based on your knowledge of the course. But having a large number of very small assessments, each of which might need multiple attempts, is a recipe for madness — see below.

But be honest, too, in that the vast majority of us will have to do some grading (or at least providing evaluative feedback) on student work as part of our jobs, and probably lots of it. We are not trying to be lazy. We are just trying to anticipate grading overload and stop it before it starts by being smart humans when we design our courses. Even if you don’t have direct control over course design (e.g. you’re teaching a highly standardized course that follows a set plan that is out of your control), look for ways to do what you can with what you have.

This is different from “teaching to the test”. Teaching to the test means restricting instruction to the very small subset of material and questions that a given test will cover. While active learning should instantiate the standards, we are free — I would say obligated — to introduce a full spectrum of ideas and tasks related to, but not identical to the standard we will eventually assess.