Achievement goal orientations and alternative grading

How different approaches to grading can impact students' goal mindsets

This week we’re featuring a guest post from Drew Lewis, Associate Professor in the Department of Mathematics and Statistics at the University of South Alabama. He is a longtime proponent of alternative grading in all its forms and one of our co-organizers at The Grading Conference. You can connect with Drew on Twitter at @siwelwerd.

Most instructors who use an alternative grading system will readily agree that it helps lower students’ stress and anxiety. Most will also say that it promotes a growth mindset (as suggested by the name of this blog). In a previous post, David dug into the details of the former claim; here, I would like to more closely examine the notion that alternative grading practices can help foster a growth mindset.

Growth mindset as a concept has become deeply embedded in the collective consciousness of educators over the last 15 years. Briefly, growth mindset refers to the belief that one’s abilities are malleable and can be improved. This contrasts with a ‘fixed mindset’, the belief that one’s abilities are fixed. This idea originated in the work of Carol Dweck some 30 years ago and has been researched since; it seems to have become quite well known following the publication of Dweck’s 2006 book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, which was targeted at a general audience, including parents. Recently, large studies have shown that even a short intervention can improve students’ mindsets, and that this improves students’ achievement.

Readers will likely immediately see the connection between a growth mindset and alternative grading, in which students are provided many opportunities to demonstrate their learning and are not penalized for past attempts. However, there seems to be little empirical research that supports this claim. Negative results can readily be found, though perhaps a larger, well designed study with greater statistical power might detect a change. My personal take is that growth mindset might be too coarse of a measure to impact with indirect interventions such as altering the grading system, so I spent some time exploring the literature. In particular, I wanted to see whether there are more specific constructs related to growth mindset that might better capture this difference most practitioners feel that alternative grading provides.

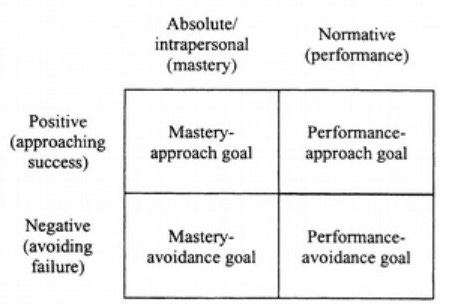

What I learned is that, historically, the idea of growth mindset grew out of work on what is now called achievement goal orientation. Originally, achievement goal theory divided individuals’ motivations (“goals”) into two categories: mastery goals and performance goals. Mastery goals refer to an individual’s desire to learn a skill or to do well at a task, while performance goals are a desire to demonstrate competency relative to others1. Later, researchers refined the model to add a second axis of approach versus avoidance. Here, an approach orientation indicates a desire to succeed, while an avoidance orientation is a desire to avoid failure2.

Broadly speaking, of the four categories, a mastery approach goal orientation is most associated with positive outcomes such as improved learning and academic performance. While performance approach goals have some positive benefits, they do not have the same connection to academic performance. Performance avoidance goals, and more recently mastery avoidance goals have been found to be negatively correlated with students’ academic performance. Researchers have also found a correlation between growth mindset and mastery approach goals, while a fixed mindset is associated with avoidance and/or performance goal orientations.

Similar to the claims most of us make that alternative grading systems promote a growth mindset, I think most practitioners would also argue that alternative grading systems promote a more productive achievement goal orientation (i.e. mastery over performance, and approach over avoidance). Indeed, one of the first changes I noticed after switching from a traditional, weighted-average grading system to Standards-Based Grading (SBG), was how students reacted after I handed back an exam. Previously, they would often turn to their neighbor, compare the number at the top, and then shove the exam in their bag to never be seen again. This behavior seems to very closely match the idea of a performance goal orientation, focusing on how one student’s number compared to others’. Now that I use SBG, when students get exams back they turn to their neighbor and say things like “I still don’t know how to do X, did you get that one? Can you show me?” The key difference seems to be that the focus is on clearly defined learning objectives, one of the pillars of alternative grading.

The other three pillars of alternative grading also seem to promote more productive achievement goals. I like to combine and paraphrase the second and third pillars as focusing on feedback rather than evaluative marks (“grades”). Here, there is evidence in the research literature to support this claim, namely a 2011 paper of Pulfrey et al. This study considered what happens in three conditions. In one group, student work was marked with a grade alongside feedback. In a second group, only the grade was provided, and in the third group, only feedback was provided. They found that, regardless of whether there was feedback or not, the presence of the grade increased students' performance avoidance goals. Put another way, providing students feedback without a grade lowers their performance avoidance goals.

The final pillar is to allow students many attempts to demonstrate their learning, whether this is reattempts or revision of previous work, without penalty. By removing penalties for failure, we promote an approach goal orientation. Moreover, the focus on (re)attempting to demonstrate learning until meeting a clearly defined standard provides a focus on mastery of a particular skill or topic, rather than a performance approach of comparing one’s progress to others.

While I think there is a solid theoretical case, there seems to be very little literature examining the relationship between alternative grading systems and achievement goal orientation, making it a very fruitful area for new research. One could ask simply whether alternative grading systems as a whole improve achievement goal orientations. I suspect that there are also differences among systems and their impact; for example, Ungrading, which often has a complete absence of evaluative marks, could have a larger impact than Standards-Based Grading, for example, which still includes an instructor rating, even if it is categorical rather than numerical.

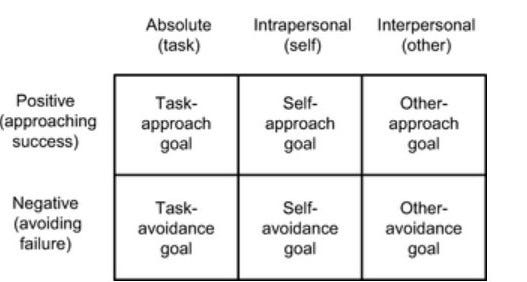

Differences among grading systems might be more clearly illuminated by the most recent developments in achievement goal theory. The 2x2 framework has recently been expanded into a 3x2 model by subdividing mastery goals into task-based goals and self-based goals (with performance goals being renamed other-based goals). Task-based goals relate to completion of a task, while self-based goals relate to one’s own personal trajectory. In this framing, we see how systems like Standards-Based Grading are optimized to promote task-based goals, while reflection-heavy systems like Ungrading are more aligned with self-based goals.

In closing, I would like to issue a call to the alternative grading community to conduct more research into these claims that we generally agree upon but lack compelling empirical evidence for. While we may not be able to draw conclusions from our own context, collaborations across disciplines and institutions will be key to creating robust study designs to answer some of these questions.

References

Elliot, A. J., & McGregor, H. A. (2001). A 2x2 achievement goal framework. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(3), 501-519. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-3514.80.3.501

Elliot, A. J., Murayama, K., & Pekrun, R. (2011). A 3 × 2 achievement goal model. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(3), 632–648. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023952

These definitions likely bring to mind the dichotomy between criterion-referenced grading and norm-referenced grading.

More details on the achievement goal construct can be found in Elliot, A. J. (2005). A conceptual history of the achievement goal construct. In Handbook of Competence and Motivation, edited by A. J. Eliot and C. Dweck, 52-72. Guilford.

Thank you for the insight, Drew. That little table for achievement goal framework is a helpful discussion point as I talk with others about MBG.

This video certainly isn't formal research (https://youtu.be/9vJRopau0g0?t=21), but time 0:20 - 2:20 shows a super interesting result of not penalizing learners (even when the points aren't real). When playing video games, people seem to naturally have a "task-approach goal mindset".