Will the circle be unbroken?

Reflections on a recent study of anatomy & physiology instructors

Greg Crowther is a tenured instructor in the Department of Life Sciences at Everett Community College (north of Seattle), where he teaches A&P to pre-nursing students and others. As a student, he ignored learning outcomes lists because their connections to assessments were not clear to him. As an instructor, he strives to make those connections more transparent and meaningful.

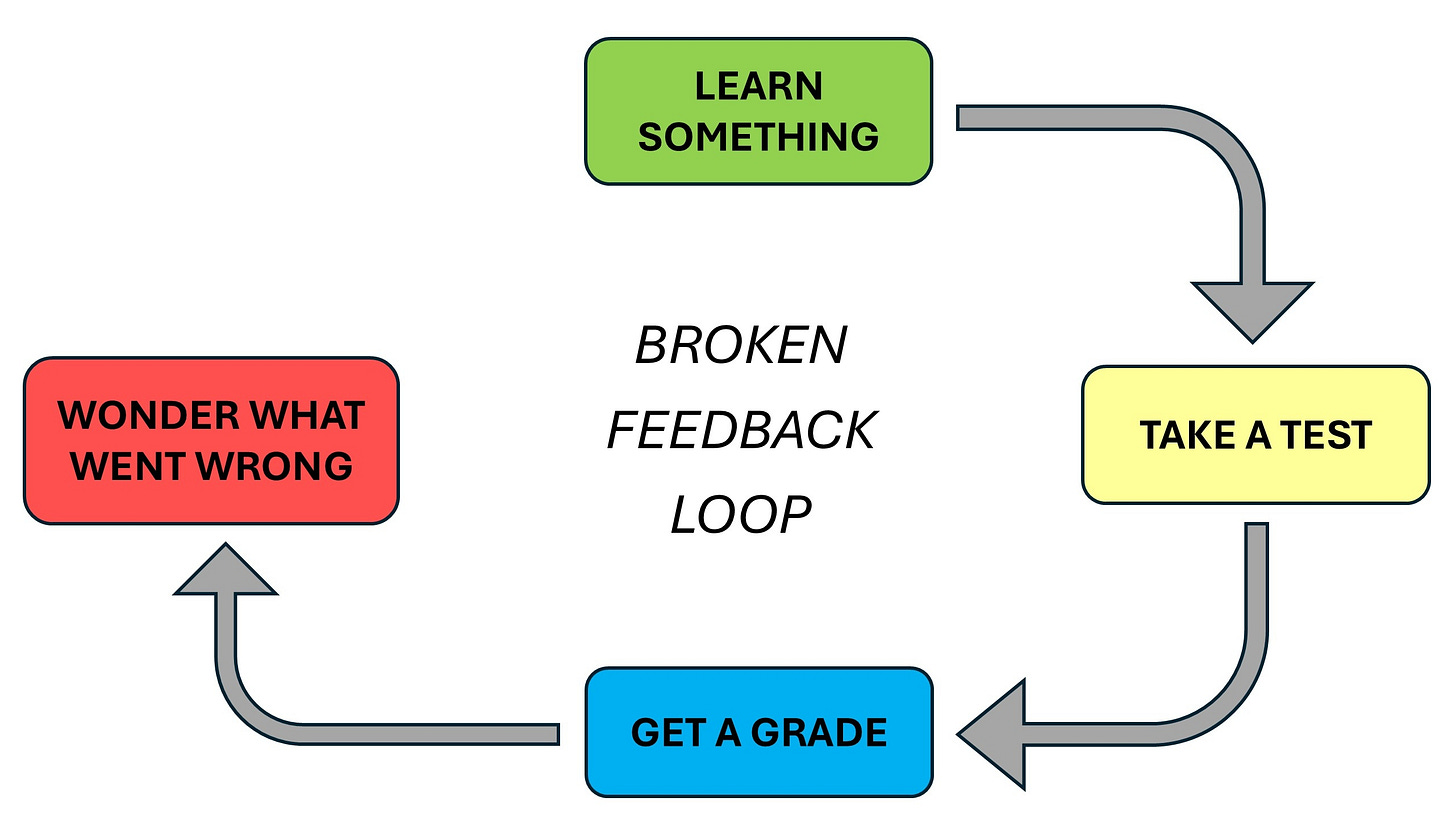

The Grading for Growth blog is obsessed with feedback loops, and rightly so. As Robert has said,

When we learn anything of significance, it’s because of our engagement with a loop: We do something; then we get helpful feedback from a trusted source; then we analyze and reflect on the feedback; then we make mindful changes to our processes. And then we start the loop over with inputs that are informed by the previous iterations.

This circle of performance, feedback, and revision has also been emphasized by other guest writers and is central to my planning of summative assessments, which in my courses (Human Anatomy and Human Physiology) include six 150-point tests plus three test-retake opportunities. However, while attending a biology education conference last year, I observed a moment of Q-and-A that suggested that some dedicated, experienced instructors may regard feedback loops differently than I do.

As another professor’s conference workshop on three-dimensional assessments wound down, a fellow attendee’s hand went up.

“So,” she asked, “once you’ve written these 3D test questions, do you, uh, reuse them from semester to semester?”

The dialogue that followed suggested to me that this professor was highly conflicted. It seemed that she wanted to give authentic, challenging tests, but couldn’t imagine writing a fresh batch of them each term. However, reusing the tests would necessitate “locking them down” so that they weren’t leaked, and not returning the graded tests would mean that students couldn’t see their mistakes and learn from them -- an idea that made her uncomfortable.

This professor remained in my thoughts during the flight home and beyond. Here was someone who presumably cares deeply about her students’ learning (as indicated by her attending this conference and this workshop), yet she would consider withholding test feedback other than overall score, which would essentially break the feedback loop. Was this person an anomaly, or are such practices prevalent in biology (as they are in math, according to Sharona Krinsky)?

From inspiration to publication

I returned home with a pitch for Ben Wiggins, a fellow community-college biology instructor and frequent collaborator. Could we do a survey to see whether the non-return of graded tests was common among undergraduate instructors? Ben said yes to this, and also suggested additional questions to give us a broader, more comprehensive view of instructors’ exam practices. Since we did not have funding for a huge study covering all of science, or even all of biology, we decided to focus on a relatively well-defined subfield, anatomy & physiology (A&P), with a corresponding national organization (the Human Anatomy & Physiology Society, or HAPS). The existence of HAPS allowed us to recruit A&P instructors in a systematic way and then report the results back to these same instructors via the society’s journal, HAPS Educator (to avoid the impression that we were sneakily documenting members’ questionable behaviors and then “telling on them” to external audiences).

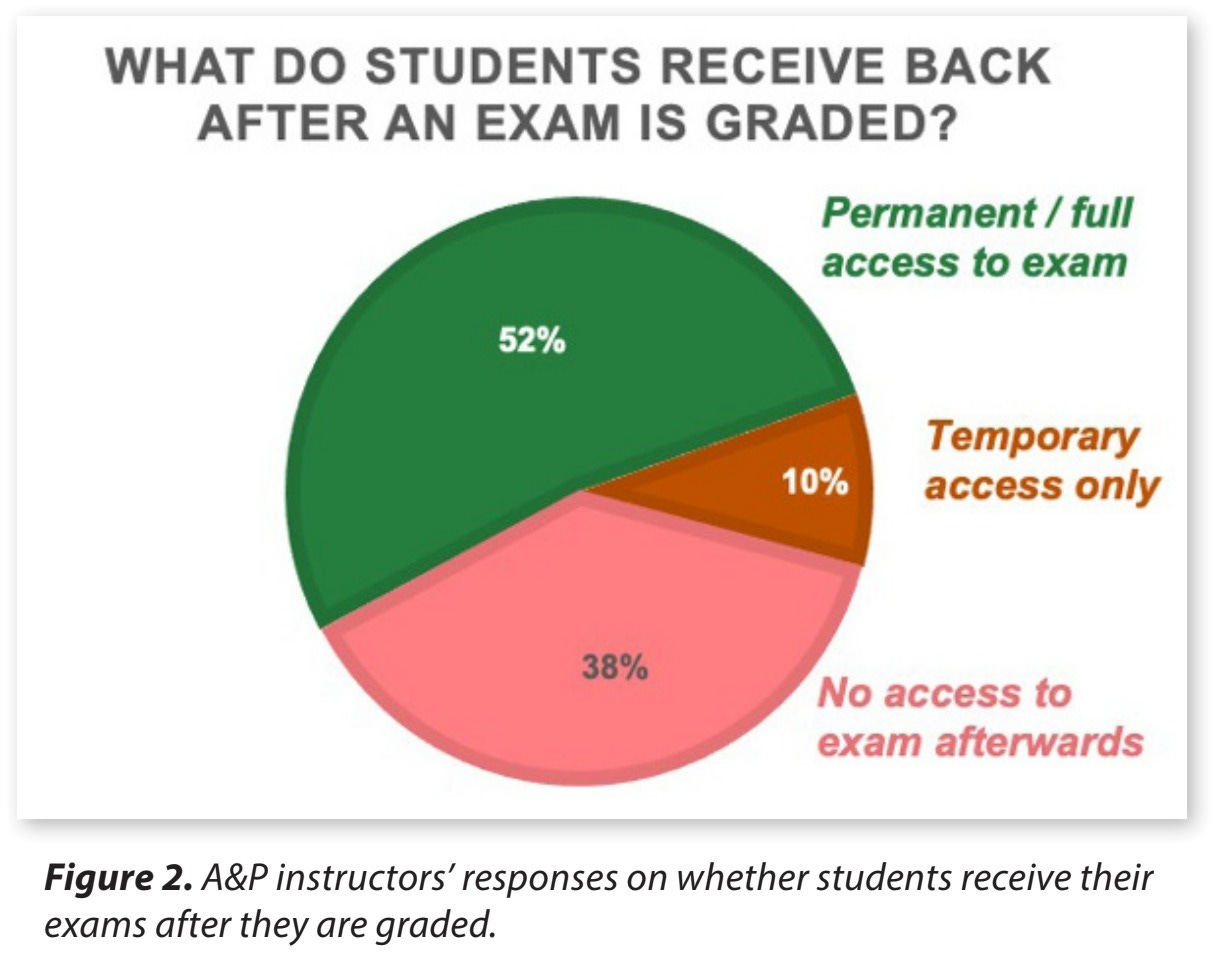

We found that, of the 63 A&P instructors surveyed, 24 (38%) did not give students any access to their graded tests, while another 6 (10%) gave them only partial or temporary access, e.g., only during office hours (Wiggins & Crowther, HAPS Educator 28(3): 24-44, 2024; see Figure 2, which is reproduced below). That is, nearly half of these instructors prevented or limited their students’ review of their own graded tests!

Had we polled a bunch of lackluster teachers who don’t really care about their students’ learning? There’s little reason to think so; most of them reported providing study guides, holding review sessions, and/or supporting students in other creative and time-consuming ways. We thus observed a paradox: these instructors seemed strongly committed to their students, yet they often did not provide test feedback that would help students learn from mistakes. The survey data did not let us fully resolve this paradox, but nearly every respondent reported reusing test questions from term to term, and we hypothesize that many of them keep the graded tests to maintain test integrity (i.e., prevent cheating).

Without meaning to throw anyone under the schoolbus, we believe that test-sequestering practices deserve further scrutiny by the STEM education community. We share the concern articulated eloquently by Sharona Krinsky: “How is any student supposed to learn from their mistakes if they do not have access to those mistakes to learn from?”

To me, the basic solution (as addressed in math by Steven Clontz’s Checkit project) is clear: you need multiple equivalent assessment questions for each Learning Objective (LO).

This is straight out of the alternative grading playbook; if your students get multiple chances to meet a standard or objective, you’ll generally want to have multiple versions of the corresponding assessment. But I claim that the idea also applies to courses that do NOT use alternative grading. Even with a one-and-done assessment, students probably want and definitely deserve to see why they got the grade that they got. And if giving a test back means that that test is “spoiled” and a new version must now be generated during the next term, that’s probably what we should do.

How reformatting LOs can help

If the prospect of generating many versions of your tests seems daunting, I have a recommendation for making that more feasible. It’s not a quick fix, though; it involves rewriting your Learning Objectives (LOs)!

To understand my approach, it is helpful to know some LO basics (e.g., as explained by Rebecca Orr and colleagues). First, LOs include broad course-level LOs and finer-grained instructional or lesson-level LOs. My approach generally leaves course-level LOs untouched but requires editing of lesson-level LOs, which generally are the LOs that correspond most directly to individual test questions. Second, some (e.g., Orr et al.) strongly recommend that each LO include a specific context or set of conditions in which an action will be performed.

I ensure that my LOs include this context by writing them in the general format of “given X, do Y.” Among other benefits (such as elevating the LO’s Bloom level), this format makes it relatively easy to generate multiple equivalent versions of questions (sometimes called isomorphic questions). All you need to do is swap out the specific version of X that is given to the student!

A couple of examples should clarify what I mean.

Example #1: In my Human Anatomy course, I want my students to understand the concept of the “anatomical position,” in which a person stands a certain way: facing forward, feet flat on the ground, legs about shoulder width apart, toes painting forward, arms at sides with palms facing forward. A conventional LO might ask students to define the anatomical position. In contrast, my LO states, “Given a picture of a person, determine ways in which their position is and/or is not consistent with the anatomical position.” From one term to the next, it’s easy to change the picture to show a different person who does and does not match different aspects of the anatomical position.

Example #2: In both Human Anatomy and Human Physiology, I want my students to be able to predict the flow of blood in and out of the heart through various blood vessels in multiple steps. Most collections of LOs that I’ve seen do not directly cover this skill, but I’ve written one: “Given a current location of blood, answer questions about the order in which cardiovascular system structures are encountered.” The location could be given in a diagram or in words, as in the following question: “A red blood cell is currently in the common iliac vein. Which of the following is it most likely to go through next? (A) common iliac artery, (B) internal iliac vein, (C) pulmonary vein, (D) superior vena cava.” This question could easily be changed by changing the initial location of the red blood cell (and/or by changing the answer choices).

I have hundreds of additional examples, but these two are probably enough for you to get the general idea. In short, having a LO in a “given X, do Y” format facilitates the generation of multiple questions that differ in what exactly is given to students to kick off the question.

Conclusion

There are understandable practical reasons why even conscientious, dedicated instructors may not return graded tests to their students; however, this practice disrupts the feedback loops that underpin all significant learning. A broken feedback loop is no longer a loop; it is a dead end. Whether or not instructors engage in alternative grading practices, they need to be able to create multiple equivalent versions of tests so that their students can get back the version that they took and learn from it. Using LOs that include context -- e.g., by using the “given X, do Y” format -- makes it easier to spin off multiple questions about the same LO.

Every time I prepare a test, I’m reminded that making tests returnable is a significant burden on instructors. Nevertheless it’s a burden that we should accept. When the circle of learning is broken, let’s repair and restore it for the sake of our students.

That makes a lot of sense for LOs based on "do". How does this work for LOs based on "explain"? In this case, I need non-isomorphic problems so that the student can't simply memorize definitions/processes without truly understanding the motivation/mental model behind the process.

We, as instructors, are required to keep student exams at my university. So, I only give them temporary access.