The Drama Triangle of Grading

Understanding the stress of grading and a path towards empowerment

Today we bring you a guest post by Jordan Freitas, an Associate Professor of Computer Science at Loyola Marymount University, a Jesuit University in Los Angeles, CA. She works on developing data collection and management systems that account for unique contexts and enable new analysis methods. Her favorite classes to teach are networks and ethics. She can be reached at Jordan.Freitas[at]lmu.edu.

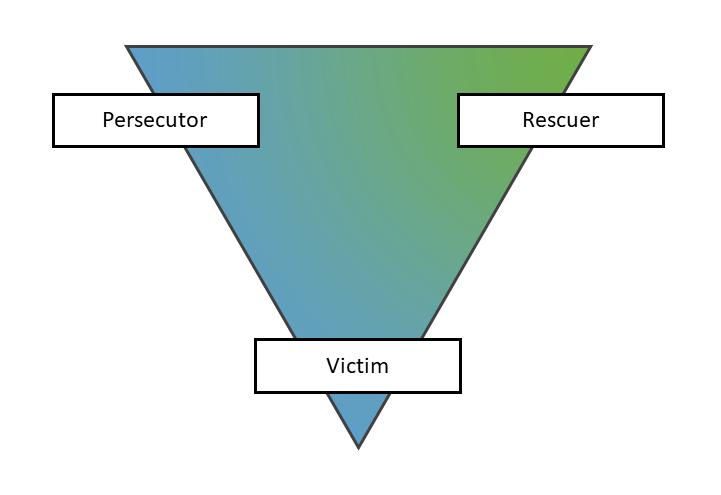

The Karpman Drama Triangle is a framework from relationship psychology which describes three unproductive roles we tend to fall into in states of stress: persecutor, rescuer, and victim. We might assume different corners of the triangle in different contexts with different people, and sometimes dwell in the spaces between or move all the way around as a situation unfolds. Each role describes behaviors we engage in from places of fear, guilt, shame, or some combination.

If traditional grading methods have not felt aligned with who we want to be as educators, it follows that before we adopt alternatives we will have experienced some “drama.” Fortunately, there is a companion model described in The Power of TED* (*The Empowerment Dynamic) by David Emerald Womeldorff. The Empowerment Dynamic offers each role in the Drama Triangle a more empowered counterpart along with directions for moving away from the underlying fear, guilt, or shame driving the behaviors of the Drama Triangle and towards healthier connection and more effective ways of relating.

This article explores how the Drama Triangle and Empowerment Dynamic shed light on why so many faculty have had a bad time with the process of grading and corresponding improvements to seek when adopting alternative strategies.

I used to regularly commiserate with faculty colleagues, all of us soaking in the stress around grading. Coming from that place of stress, I have experienced and observed the Drama Triangle of typical grading schemes play out along the following lines.

Persecutor: the instructor determines the criteria and boundaries defining what is “good” and corresponding point values. Their preferences and judgements dominate and they see mistakes or divergent behavior as punishable. Students are often blamed for falling behind or not being engaged–never mind whether the workload is reasonable or not, never mind if the material is relevant or engaging.

Rescuer: “I am nice, and so I will [fill in the blank] even though I would rather not.” Grant a request for an extension. Give partial credit. Lower the letter grade boundary at the end of the term, because not enough students have earned A’s. Stay after a long class period to answer questions about what will be on an exam. Schedule meetings with students who can’t make it to office hours. And so on. Many of us recognize and regret the harm done by typical grading schemes and our complicity in the inhuman amount of stress imposed on university students. Busy, guilty, and anxious, we consider whether to “save” them without interrogating the roots of the issue.

Victim: Faculty sometimes have a limiting belief that there is no way to avoid being overworked. This setup is ripe for experiencing feelings of shame when we believe we are falling behind. In turn, shame can lead to avoidance of seeking or receiving care and support. When feeling overworked, faculty may begrudge responding to requests for accommodations.

Alternatively, the corresponding Empowerment Dynamic roles we can move into with alternative grading are: challenger instead of persecutor, coach instead of rescuer, and creator or survivor/thriver instead of victim.

Rather than persecute students by blaming or shaming them for unmet expectations, the challenger creates a classroom culture from a place of knowing students are capable of learning and thinking deeply, centering how the curriculum aligns with students’ own unique goals and interests (which implies making space to hear them), and caring about our role in their personal and professional growth. Faculty and students alike can learn to identify and honor our boundaries without blame or apology. When grades are not the primary concern, faculty can offer students perspective and feedback while challenging them to critically examine their own work as well as to own, celebrate, and advocate for recognition of their accomplishments. Freeing students from the threat of judgment and withholding of points as a punishment for not complying with a rubric and timeline enables a new level of transparency in the faculty-student relationships which can then inform more genuinely student-centered processes.

Growth requires some struggle. Learning should be difficult because the topics are deep, not because grades artificially impose additional stress. The challenger aims to help students move through the struggle to learn, grow, and be their own best selves. There is a loving detachment that allows and encourages students to make mistakes, as well as to be challengers in the classroom community who help instigate fruitful dialogue. The persecutor pushes conformity and relates with conditional positive regard, in other words esteem is earned and lost with class performance. In the role of a challenger, freedom, trust, and positive regard are assumed.

Typical grading schemes are a sorting process. It can be obvious which submissions will end up with As or Fs, while those around the edges of grade boundaries likely require more attention in order for a letter grade to be determined. This uneven and bias-prone process is occupied and defended by the persecutor role. Alternative grading ideally implies biases have one less arena in which to manifest if students’ work doesn’t need to be sorted into letter grades and faculty time spent on evaluation can be more evenly distributed. Students’ own biases and positionality may well lead to over or underselling themselves and their work. In this regard too, they need challengers.

The next role embodies encouragement, direction for continued improvement, and a culture of teamwork that recognizes everyone's presence and contributions matter. Coaches help players build on previous successes and existing strengths, and break down a larger goal into achievable plays. Instead of rescuing students from education-related stress, de-emphasizing grades dissolves the inclination to save students from the stress grades impose. When the learning environment is safe, students don’t ask to be saved. They are freer to be brave. Studies have also shown that when feedback is given with a score versus without a score, students are more likely to read and incorporate the feedback if there are no accompanying grades.

The coach role is particularly important because of the common misconception that alternative grading means letting students off the hook, being too easy to the point they quit doing work. What matters is the role we assume with alternative grading: rescuing them from hard work or removing barriers that make learning something hard artificially harder. As a coach, the instructor is able to hold students accountable not to external incentive and punishment, but to their own goals, growth, and standards, and to the success of the whole class.

Whereas a victim is characterized by hopelessness, a creator survives and thrives by meeting adversity with creative solutions. The way to move from victim consciousness into an empowered creator and survivor/thriver as an educator is to recognize limiting beliefs we have that turn out to be untrue, and turn our attention towards what we can control, change, and create instead. Grades have become a cornerstone in educational settings. However, ranking, sorting, and manipulating students into compliance are at odds with ideal learning environments1. Faculty have extensive freedom to decide whether these have a place in our courses, and even reconsider the purpose of education as our society changes so rapidly. We are free to create new assessment practices more aligned with inclusive pedagogy and innovative teaching.

Concluding Thoughts

Rethinking how we assess learning is no small task. Much of the hesitation to try alternative grading comes from a fear of increased workload. We already spend an incredible amount of our time grading. My experience has simply been a creative reallocation of that time. I gave up trying to decipher and score assignment submissions, then devise and calculate formulas to average those scores. Instead I meet with students individually or in small groups as regularly as I can. It has blown my mind how much more I learn about my students this way, and I don’t find the time spent tedious or draining. These meetings also directly inform regular adaptations of my plans for the class to better meet the students’ needs and interests. Instead of pressure to justify a rubric or apply it with perfect fairness, I’m able to listen to what my students are experiencing and offer guidance based on my honest understanding of how the course material aligns with their educational and professional goals. These kinds of shifts can be uncomfortable and disorienting when students are used to having a more passive voice in their courses, but this is the discomfort of learning to trust and think for themselves.

When so much is at stake over GPAs, we have set students up to become preoccupied with obtaining and protecting their points, and then this concern takes up an outsized proportion of interactions between the student and instructor. Anticipating students’ counter-arguments to lost points on assignments, feedback from instructors can subconsciously take the form of justification instead of helpful direction. Seeking authentic learning experiences for their own sake is also part of the human experience. Students deserve instructors who assume their desire to learn is genuine.

Students’ effort to calculate how to balance competing demands without jeopardizing grades in multiple courses among other responsibilities reminds me of an egg-and-spoon race. A persecutor would be concerned with timing participants and disappointed with dropped eggs, whereas a challenger reminds participants of the organizing principles that give shape to the event while not taking mistakes personally. A rescuer might pass out bigger spoons while a coach offers strategy, technique, and encouragement. A victim may likely be preoccupied with not having the right shoes for this activity, and a creator is taking their shoes off all together. The grass feels amazing! At the end of the day, the eggs will not end up mattering for much. The purpose was to play. So too, if our purpose is to teach and students’ purpose is to learn, educational systems will better serve everyone by moving away from grades.

Most universities in the United States still require faculty to submit final letter grades at the time of writing. However, the process by which those grades are determined is almost completely up to the discretion of the faculty. My hope is that we will recognize how much freedom we have to reconstruct those processes, and that we do so from a conscious place of empowerment instead of stress.

As described by Motivation and education: The self-determination perspective by Deci et al. and Uncommon Sense Teaching by Oakley et al.

Interesting as always, Jordan—but I find it frustrating that we continue to treat grades as if they’re the best or only tool we can use to assess learning. The truth is, as long as a final grade remains the marker of performance, we’re not escaping the “Grading Triangle.” You can adjust who determines the grade and how, but the structure remains intact. Even assuming the best intentions—teachers committed to learning, students eager to grow—the grade system still defines the boundaries of what “counts.”

Let’s not forget that grades themselves were an innovation of the Industrial Age, created alongside other systems designed to sort, rank, and standardize. Ever wonder why we don’t see references to the “grades” given to Einstein, Douglass, Austen, or Curie? Because the concept is modern, mechanical—and deeply embedded in a worldview that prizes efficiency over depth.

If we can collectively acknowledge that grades are not the only—or even the best—way to assess learning, only then can we begin exploring true alternatives. One example: in the world language field, learning is increasingly assessed through proficiency levels, not averages. Some programs are already basing grades (when required) on demonstrated levels of communication, not points collected.

Grades may have served a purpose in a past era, but we’ve outgrown that model. If we’re serious about growth, we need to let go of Industrial Age tools that no longer serve 21st-century learners.

“To live in an evolutionary spirit means to engage with full ambition and without any reserve in the structure of the present, and yet to let go and flow into a new structure when the right time has come.” – Erich Jantsch