Student-Led, Instructor-Guided

Using Self-Assessments in Project-Driven Classes

This week’s guest article is from Michael D. Johnson, who teaches writing, design, and game studies courses at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana. He also serves as Assistant Director of the Writing Program, where he prioritizes mentorship, professional development, and supporting undergraduate research. While initially introduced to alternative grading in his doctoral program (2012), he returned to exploring its potential for enhancing student-centered learning in 2022. He is now actively building an Alternative Grading Community with colleagues, dedicated to promoting and supporting instructors in implementing these approaches in their teaching at Purdue. Beyond academia, Michael is a proud parent to his two cats, Tele and Virt, and enjoys board gaming and watching horror films.

Over the last three semesters, I’ve been exploring how self-assessments can enhance student learning by increasing student agency and investment while reducing the anxiety that often accompanies traditional approaches to grading. In this post, I share my recent efforts at developing and implementing a framework for student-led assessments in writing-intensive and project-driven courses. I hope that whether you teach a course that involves writing-intensive projects or not, you can still gain some insights into how self-assessments may be a valuable tool within your own alternative grading toolkit.

The Long Way Around

My field of study—Composition and Rhetoric—is no stranger to alternative approaches to grading, stretching back at least three decades with early efforts by Ira Shor on critical pedagogy and continuing most recently with work by scholars such as Asao Inoue. For me, personally, I first came across alternative grading in 2012 at the start of my PhD program at Ohio University. At that time, all incoming graduate students who would be teaching first-year composition were required to implement a “grading contract.” This particular version of a grading contract was based on a 2009 article by Jane Danielewicz and Peter Elbow, and, in short, established a set of parameters that, if met, would result in a student getting a grade no less than a “B” in the course. While I found this initial foray into alternative grading interesting, I didn’t have enough experience with teaching (and with traditional grading systems) to fully appreciate the practical and philosophical shifts brought about by using a contract grading system, let alone to manifest those shifts in my own courses. Although I moved away from grading contracts after my first year, I continued experimenting with various approaches to providing students with feedback, including an initial attempt at collaborative assessment in the Fall of 2016.

In 2021, I began working at Purdue University, where I serve as Assistant Director of the Writing Program. Purdue is a public, land-grant university in Indiana with an undergraduate population of over 44,000 students. The university is a major research institution and is nationally renowned for a number of its STEM programs. The Writing Program is housed within the English Department and supervises courses related to professional, technical, and first-year writing. During my initial adjustment to teaching at Purdue, I adopted a more standard approach to grading. However, in the Fall of 2023, I participated in the IMPACT program at Purdue, a faculty development program focused on creating “autonomy-supportive and inclusive learning environments” rooted in self-determination theory. While engaged in this program, I returned to my interest in alternative assessment and developed a new self-assessment framework to pilot in a first-year composition course focused on academic and research writing. This academic year, I have implemented and continued to refine the framework within English 309: Digital Design and Production.

A Framework for Student-Led, Instructor-Guided Assessments

In this section, I share my framework for student-led, instructor-guided assessments. The highlighted course design considerations within this framework are what directly shape the self-assessment instrument I use in English 309, which I will share following this overview.

Course Context

English 309: Digital Design and Production is a project-driven course with a strong practitioner’s focus, currently capped at 20 students. While the course is part of the Professional Writing major, it also fulfills an upper-division writing requirement and is open to all majors. This context results in a relatively diverse student population with varying levels of design experience, knowledge, and skills. Over the course of the semester, students will learn to apply design thinking, conduct user research, implement design principles, use design tools, and collaborate effectively to approach and solve “design challenges” (such as designing a usable and useful document for a student club or organization). Despite being project-driven and design-centric, the course involves considerable writing. Within the context of English 309 (or any other project-driven course), writing is used as a flexible tool to support design thinking.

A Note on Categorizing Coursework

To emphasize the design process that undergirds the course, I categorize student work into three areas that correspond to phases of a project's life cycle: navigating a project, finalizing a project, and evaluating the project.1 For English 309, I use the following framing for students:

Practice, Process, & Preparation Work (e.g., “low-stakes” work): This category includes activities & assignments that largely either support a Design Challenge—such as inspiration & ideation work, prototyping & testing work—or that ask students to engage with course material and concepts that they’ll put into practice while completing Design Challenges throughout the semester.

Design Challenges (e.g., Major Assignments): This category includes small- and medium-scale projects that make up the backbone of the course and provide practice in various aspects of design.

Design Debriefs (e.g., Reflections): This category includes assignments that ask students to reflect on the process of completing a Design Challenge. Generally, these reflections task students with discussing their design process, analyzing their design choices, and reflecting on their learning and growth as a designer.

By providing a consistent structure that mirrors the design process, these categories facilitate students' meaning-making in the course, a process that ultimately enhances the depth and value of their self-assessments. Furthermore, not only do these categories provide a flexible structure for organizing student work in courses with low-stakes work and projects, but they also simplify gradebook management and establish a foundation for implementing other alternative assessment practices, such as contract grading or specs grading.

A Note on Rubrics

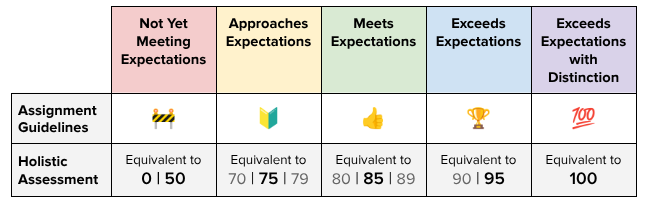

For all graded work in the course, I use a flexible expectations-based holistic rubric designed to simplify the feedback process.

This minimalist rubric features a single feedback criterion based on the guidelines provided for a particular assignment. Furthermore, it features five levels of performance with the following descriptions:

Not Yet Meeting Expectations: “You did not do what the assignment asked of you. Your work is either incomplete or missing.”

Approaches Expectations: “You mostly did what the assignment asked of you. Your work demonstrates an ability to meet the expectations of the assignment but suggests that you may need to allocate additional resources or try a different approach to fully meet expectations.”

Meets Expectations: “You did what the assignment asked of you. Your work demonstrates proficiency, competency, and/or understanding.”

Exceeds Expectations: “You excelled at what the assignment asked of you. Your work demonstrates a high level of proficiency, competency, and/or understanding.”

Exceeds Expectations with Distinctions: “You went above and beyond what the assignment asked of you. Your work is of exceptional quality and has earned additional merit beyond the ‘Exceeds Expectations’ designation.”

An earlier version of this rubric used a single-point framework. However, in response to student feedback, I re-designed it to approximate a “traditional” grading scale to provide students with an easier-to-understand frame of reference. That said, I use these expectation-framed designations in the grade book in place of the corresponding letter grade ranges to stress that these are not simple replacements for letter grades and mean something specific within the context of our course.2

A Note on Recognizing and Rewarding Student Labor

The shift away from traditional grading can prove anxiety-provoking for some students. To support students and alleviate any potential concerns, I have found it beneficial to incorporate an Effort-Based B Guarantee into my courses. This guarantee establishes “effort thresholds” derived from the expectations-based rubric that students can meet to ensure a grade of at least a 'B' in the course. On the occasion that a student's initial effort may not meet the established “effort threshold” for a given assignment, that student is encouraged to revise their work based on provided feedback to meet (or exceed) those expectations. While the specific criteria may vary from semester to semester (and for different courses), they typically involve demonstrating a 'Meets Expectations' level of performance in the following areas:

Most Practice, Process, & Preparation assignments.

All Design Challenges.

All Design Debriefs.

Attendance (e.g., missing no more than five classes).

Although student-led assessments can be implemented effectively without this additional support system, I find that providing an achievable pathway for securing a “guaranteed” ‘B’ strongly complements their use within the course. As one might imagine, student-led assessments demand greater self-direction and investment from students. This shift in engagement has the potential to cause anxiety for students who have become accustomed to the more procedural nature of courses driven by traditional grading systems. However, the Effort-Based B Guarantee—especially when buttressed by a growth mindset classroom—is one strategy for reassuring students that their efforts are not only valued but also a significant driver of their success.

The Student-Led, Instructor-Guided Assessment Instrument

As a general overview, students complete several self-assessments across the semester that play a key role in determining their overall grade in the course. Typically submitted every four to five weeks, these assessments ask students to analyze their experiences in the course and provide evidence-based reflective discussions of their performance, engagement, and growth. Although students are asked to share what grade they believe is warranted based on their performance and engagement for the weeks under consideration, these assessments are not simply self-assigned grades or a venue for “pitching” a grade; rather, they provide a guided process for students to share their understanding of their progress and standing in the course with me. As such, student-led assessments invite them to become active partners in their educational experience, engendering a sense of self-authorship through my seeing, hearing, and valuing their perspective.

While the specifics of the assessment framework have evolved with each implementation, students are consistently asked to self-assess their engagement in three key areas: Course Preparation & Investment, Course Participation, and Course Contributions. I selected these engagement aspects to complement the more instructor-driven coursework categories I outlined earlier. By asking students to share their understanding of their efforts and experiences in the course, students can highlight consequential moments in their growth and development that may not always be evident or visible in completed coursework. To promote clear student understanding and guide students’ reflection, I describe these categories as follows:

Course Preparation & Investment: This category is concerned with what students do outside of scheduled class time. It focuses on both preparedness for learning and proactive strategies for achieving course success. Considerations include engagement with course materials, reading and studying habits, time management practices, assignment completion, and use of support resources such as the campus writing lab.

Course Participation: This category is concerned with what students do during scheduled class time and constitutes their active engagement in the learning process. Considerations include asking questions, answering questions, sharing thoughts or work, maintaining focus, note-taking, and collaborating with peers.

Course Contributions: This category encompasses anything that adds value to the course and/or class community. While participation primarily focuses on individual student engagement, this category emphasizes students' role as contributing members of the course community. Considerations include actions that positively affect and enhance the experiences of others in the course.

For each of these engagement aspects, students are asked to provide evidence of their perceived performance by sharing specific examples drawn from their experiences in the course, ranked in order of importance. They then elaborate on these examples in a reflective paragraph that offers further context and insights into their performance and how that performance contributed to their learning and growth in the course.

Beyond these specific engagement categories, students are asked to consider their learning through a metacognitive and forward-thinking lens. While the specific questions may vary across implementations, the overarching purpose of this set of questions remains consistent: to foster metacognition, prompting students to both celebrate the progress they’ve made and to chart their efforts in the course moving forward. This combination of reflection and forward thinking cultivates students' ownership of their learning and fosters a strong sense of agency in their growth and development as learners. For example, students are prompted to consider questions such as the following:

What moments, accomplishments, and/or achievements are you most proud of when you think about your engagement with and performance in this course for the weeks under consideration?

What are your strengths as a student and/or designer?

Where do you have room to grow as a student and/or designer?

What would you like to continue developing in or improving at as a student and/or designer?

In sum, my framework for student-led, instructor-guided assessments takes into account students' holistic experiences as a foundation for promoting metacognition and reflection. Ultimately, this empowers students by fostering their sense of investment, agency, and self-efficacy in the course. When students are invited to be active agents in their learning, they are more likely to take initiative, utilize feedback, and be accountable for their engagement.

Looking Back, Moving Forward

Student-led assessments have been a valuable addition to my teaching, and I plan to continue implementing them in my courses. However, from my experience, I've learned that if you're considering this approach, you'll need to be mindful of how you prepare students to succeed with self-assessment.3 Students have many demands—other courses, extracurriculars, financial or personal responsibilities, etc.—that often keep them focused on their next obligation. This forward-focused mindset works in opposition to the reflective nature of the assessment. Imagine asking a student to recall specifics from a particular class meeting three days ago, let alone three weeks. Therefore, it is crucial that instructors provide support and scaffolding to ensure that students can put their best foot forward and are prepared to effectively showcase their efforts.

With that in mind, here are a few simple strategies for putting students in a position to succeed on their assessments.

Provide detailed guidelines. While it might sound obvious, it cannot be underscored, repeated, or overstated enough that explicit, detailed instructions are of paramount importance, especially when students engage in self-assessment for the first time. Broad prompts, such as “Provide three examples of course preparedness,” often yield surface-level responses from students unfamiliar with self-assessment. To encourage specific, evidence-based responses, ask students to consider “any experiences, moments, skills, strategies, and/or practices” that speak to their “strengths, successes, or capabilities” in the class. To further guide them, provide students with a list of exemplifying phrases, such as “For example,” “Specifically,” “In particular,” “For instance,” and “As evidence,” to help them showcase their engagement with specific details drawn from their experiences in the course.

Set aside dedicated time. Schedule, at minimum, an in-class working session of at least 20 minutes during the week the assessment is due to allow students to ask questions and receive immediate feedback. To further support student success, offer dedicated “assessment support” opportunities in the week leading up to the deadline. These opportunities could include peer feedback sessions, expanding regular office hours, or scheduling additional, flexible hours specifically earmarked for discussing the assessment in individual conferences.

Make it routine. Integrate frequent and pointed reminders into the day-to-day flow of the course that encourage students to make incremental progress on their assessments. For example, I often use the time before class begins to display the assessment form and encourage students to use this time to jot down any notes. During class, I identify key moments of learning, participation, or contributions that would serve as strong examples to highlight on the next assessment. Additionally, scaffolding assignments (such as a “Week in Review” response) can be used to provide students with guided support and preparation as they work towards completing the final deliverable.

Are student-led, instructor-guided assessments appropriate for every classroom? No, no pedagogical approach is. That said, creating a space where students have increased agency and where their voices matter are means for enhancing any teaching practice, whether it is enmeshed with alternative grading or not. Effective teaching involves effectively adapting to the students we teach. As each semester sees us working with new students, the process of teaching is one of constantly updating our methods and revising and expanding our understanding of what works in the classroom. Student-led assessments have already demonstrated a meaningful impact in my courses, and I look forward to continuing to use and refine them. While my primary focus will remain on further developing my approach to create more engaging, equitable, and effective learning environments for my students, I am excited to explore ways to adapt and implement this framework into a wider range of educational contexts.

Do you have an idea for a Grading for Growth guest post? We would love to hear it! Just fill out this guest post proposal form and we’ll get back to you.

For those more familiar with the writing process, these areas would be process, product, and reflection.

Purdue uses D2L’s LMS Brightspace, which allows for a custom scheme to be implemented into a grade book. As such, an instructor is able to customize their gradebook in a way that letter grades are not the default.

Although I do not have the space to discuss them, I want to acknowledge two other important considerations here: framing (“How do you get students to buy in?”) and frequency (“How often should students engage in these assessments?”).