Mixing and matching SBG and Specifications (part 2)

Learning how to learn, final grades, and reflections

This week is the conclusion of last week’s post, where I introduced how I use alternative grading in a class with multiple competing goals. If you haven’t read last week’s post yet, start there first:

As a quick recap, MTH 210: Communicating in Mathematics involves both learning discrete skills and practicing with professional written communication, as well as helping students learn how to study and succeed in advanced classes. These multiple goals mean that I have to think very carefully about how to assess and grade student work in appropriate ways.

In this series of posts, I describe how I use multiple forms of alternative grading together, each supporting a different class goal. Last week, I described how I use Standards-Based Grading to assess discrete skills on weekly quizzes, while also using Specifications Grading to assess communication and synthesis on a portfolio of written proofs.

This week, we’ll begin by taking a look at learning how to learn, and how I do – or really, don’t – assess it. After that, I’ll describe how these big goals, using different assessment systems, all come together to contribute to a final grade. We’ll end with some reflections on the systems, how it’s changed over time, and where it might go next.

Learning how to learn

My third major goal for MTH 210 might sound a bit vague: How to effectively learn new math at an advanced level. As I wrote last week:

Coming into the class, students often have a very static view of math: It’s about facts, it’s about numbers, there’s always one right answer, the trick is to find the right formula and apply it. Professional mathematicians see math very differently, in terms of patterns, connections, and especially sharing and communicating precise logical ideas. Learning and studying look very different with this higher-level viewpoint, and I want to help students make this transition.

Much of this relates to the class structure, which encourages active learning, collaboration, exploration, and seeing multiple viewpoints. The class is flipped, so before each class students watch videos, read some of the textbook, review relevant prior knowledge, and attempt introductory problems on new ideas. This process models effective learning techniques. I share the ideas behind these techniques, as well as my goals and reasons, throughout the semester.

Students submit their prep work on our LMS before class, which I briefly review only for completion and reasonable effort. I’m not too picky about this — anything that attempts to address the question and addresses all instructions is OK. If students give an incorrect explanation, that’s no problem, and it provides material for me to address in class. In my gradebook, I record only whether students met this straightforward bar.

Class time is highly active, with teams of students collaborating to solve problems. Students spend at least half of each class up at whiteboards, solving problems and drafting and writing proofs. I coach students, collectively and individually, giving verbal feedback as they work. I assign competence, call out helpful strategies, and summarize key ideas. The point here is to actively engage with math and writing in a friendly, supportive, and collaborative setting, practice helpful learning strategies, and begin to build a new view of what doing math can look like.

I don’t grade this in-class work at all. That’s because I want students to be willing to try new things, struggle, make mistakes, and practice academic enabling behaviors1 and skills without the fear of summative judgment hanging over their heads. I want to be there to coach them and help them improve. All of this is practice, and so assigning a grade is unnecessary.

Not everything that matters needs to be graded, and in this case I think that the choice not to grade these parts of the class really helps, by taking some of the stress out of the learning process.

Final grades

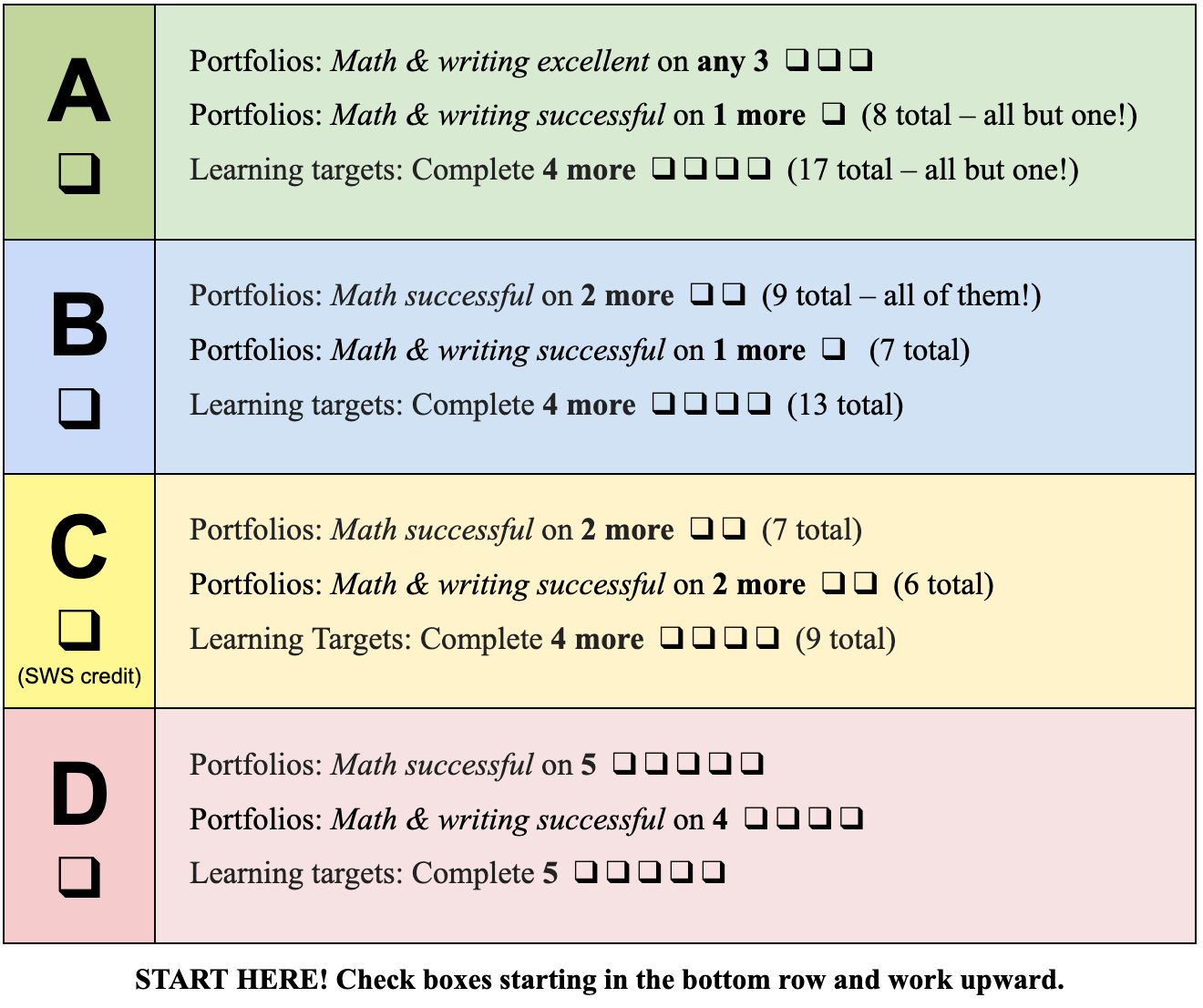

In my syllabus, I use a grade table to communicate how to earn final grades. Students must complete all of the requirements in one of its rows to earn that grade. You can see how the SBG and Specs parts of the class come together in this table:

I define “completing” a learning target as earning Successful twice. There are 18 learning targets and 9 portfolios, so even in the very highest grade there is a little wiggle room. I’ve learned through long experience that requiring perfection – for example, requiring every single target to be completed, or leaving no space in the “A” category for even a single proof with imperfect writing – incentivizes unhelpful behavior and even cheating, whereas having a small amount of flexibility encourages students to make a genuine effort. This also aligns with traditional grades, where there is still some room for imperfect work in the “A” range.

Note the “(SWS credit)” line: Students must earn a C (not C-) to earn the special writing credit for this class. I used my university’s requirements for “SWS credit” to set some of the requirements for earning a C.2

I make a printed version of this table with a bunch of checkboxes and hand it out near the start of class. Students check off the requirements as they achieve them. One side of the sheet includes checkboxes for each learning target and a place to record the mark on each portfolio problem. The other side gives the grade requirements above, reformatted in checkbox form:

There’s no question what grade a student has earned by the end of the semester – most can (and do!) tell me when I ask. If a student has questions about their grade, I begin by asking them to get out this “grade record” sheet, and if they haven’t kept it up to date, the first thing we do is talk about how to update it.

There are some more details that involve earning a + or - grade. Before I jump in, I’ll admit that this is my least favorite part about this grading system, because it involves some adjustments that can “average” or even cancel each other out. I’ve been thinking about how to improve this, but I haven’t yet found a better approach.

The final + or - adjustments have to do with two things: first the number of “daily prep” (flipped pre-class work) assignments completed, again without looking at correctness, and second the number of “core” targets for which a student earns Successful on the final exam. Based on how many of each the student completes, their grade bumps up or down.

I phrase this in terms of taking “steps” in a table of all possible letter grades:

Students begin by finding their base grade on this table, then take steps to the right or left based on completing daily prep. Specifically, the syllabus tells students:

If you complete at least 90% of the daily prep assignments, take one step to the right.

If you complete less than 75% of those assignments, take one step to the left instead (almost nobody ever triggers this case).

Next come adjustments for the final exam. As I described last week, the final exam is one last opportunity to earn Successful on any learning targets that a student needs. But there is also a required portion of the final exam. There are a few brief questions covering each of the six “core” learning targets in the class. These targets are the most essential topics in the class, so important that students must “recertify” their understanding on the final exam, even if they’ve already earned two Successful marks.3

After adjusting up or down for daily prep, students then make these adjustments, where “S” is our standard shorthand for Successful:

Move one step right if you earn “S” on all 6 core targets on the final exam.

Make no change if you earn “S” on 4 or 5 core targets on the final exam.

Move one step left if you earn “S” on 2 or 3 core targets on the final exam.

Move two steps left if you earn “S” on 0 or 1 core targets on the final exam.

The net effect of all of these adjustments is to incentivize some good things (completing daily prep, continuing to study a few key topics). At the very worst, a student who doesn’t complete many daily prep assignments, and does poorly on the final exam, can drop one full letter grade (this almost never happens). Those who show significant learning at the end of the semester can demonstrate that by earning Successful on multiple learning targets, with no penalty for needing to do so on the final exam. Students who also retain their understanding of the core targets and show this on the final exam earn a small grade boost.4

Some final thoughts

The “hybrid” approach to grading I’ve described here works very well for me. I’ve refined and simplified it over many semesters, and its current iteration fits well with my philosophy and seems to be reasonably clear and understandable to students.

Over the years, I’ve worked hard to decouple these three systems – SBG, Specifications, and ungraded practice work – to assess different aspects of the class. I used to include learning targets (skills) on written portfolio problems, in addition to using writing specifications. Not only was this complex and confusing, it was also really hard to grade. A key point in the evolution of this system happened when I realized that portfolio problems aren’t about individual skills; they’re about putting them together in a cohesive and logical way. That gave me permission not to assess learning targets on portfolios, and simplified other requirements considerably.

Another key change I made was to focus the learning targets entirely on mathematical skills. Long ago, in an attempt to make everything in the class fit into the SBG framework, I tried to wedge different types of “skills” into the learning targets. I had a separate target for “attention to detail”: For example, a student who mis-copied a problem but then solved it correctly might earn credit for the underlying mathematical target, but wouldn’t earn credit for the attention-to-detail target. Another target covered “completing daily prep assignments”. To make these work, I had to make special rules: Each of them required a large number of Successful marks to be completed, far more than any other targets, which made completing targets inconsistent and hard to explain. Once I realized that these didn’t make sense as learning targets, things got much simpler.

Nowadays “attention to detail” only matters to the extent that a student needs to show learning of the appropriate target. If they mis-copy but correctly solve a fundamentally similar problem that uses the same skill, they’ve still shown appropriate learning. If an error changes a problem to make it demonstrate a different skill, they haven’t shown understanding of that specific learning target and so earn Needs New Attempt. Similar for multiple minor errors that make it too hard to follow a solution: that doesn’t demonstrate their learning. The daily prep learning target turned into the final grade adjustment described earlier.

I also haven’t always required students to recertify core targets on the final exam. This sometimes led to situations where a student earned a high grade due to their previous work, but I suspected they hadn’t retained some key ideas. I introduced the limited but required recertification on the final exam, along with the grade adjustment that goes with it, and have been quite happy with the incentives this provides.

As I mentioned earlier, those final grade adjustments aren’t my favorite part of final grades. But each of them comes from some aspect of the class that needed a bit of fine tuning. You might wonder why I don’t include those items directly in the grade table, for example by having additional separate grade requirements for daily prep and the final exam. I’ve thought about that, but including something in a grade table makes it non-negotiable: Not doing any one item required for a grade necessarily drops the student down by at least one full grade. Neither daily prep assignments nor core targets feel so critical to me that I want to give them that much power. But, they matter enough to need to have some effect. The +/- adjustments were my solution.

In the end, I’m quite happy with this “hybrid” approach to alternative grading. Rather than trying to fit a multi-faceted class into a single grading box, I’ve used multiple approaches, each of which works well with one of the class’s goals. This feels natural and aligns well with my grading philosophy.

SBG, Specifications, and “ungrading” are not mutually exclusive. They each have strengths in different areas and work well with different kinds of assignments. In this class, I use each of them in different places where their strengths shine. Together they support the variety of goals I have, and encourage students to focus their efforts in productive directions.

If you’d like to read more about choosing SBG vs. Specifications, check this out:

“Academic enabling behaviors” are behaviors that facilitate learning, including study skills, collaboration, and even things like understanding the importance of attendance or how to use office hours. They are often part of the “hidden curriculum” of academia, so part of my goal here is to bring these behaviors into the light and illustrate why they’re important.

I also address the requirement that “at least one-third of the final grade is based upon the writing assignments” by requiring a certain number of Portfolios – well over one-third of them – to include successful writing.

If they haven’t earned two Successfuls yet, the core targets on the final exam can contribute one Successful, and still adjust the final grade as described here.

I also make a special case that if a student earns a D as their base grade, adjustments won’t drop them any lower. GVSU doesn’t have a D- grade, only an F, and so a student who satisfies the (barely) “passing” grade of D can’t be adjusted down to a failing grade. I have gone back and forth over the years about whether the adjustments can drop a student from C to C-, which would lose them the special SWS writing credit. Generally I’ve ended up not letting this happen, since the adjustments don’t relate directly to writing.

These are so helpful. I teach high school (juniors and seniors). Do you have any suggestions for how to adopt these measures for secondary school? I struggle to find balance between only grading assessments and not grading compliance and not having the assessments be so "high stakes". In addition, the students have a very hard time recognizing struggle as "ok" and part of the learning process.

Numerous students definitely need to learn how to learn. They fall flat with assignments that require multiple steps.