Can deliberate practice be motivated?

A review of a research paper that studies this question, and what it means for alt-graders

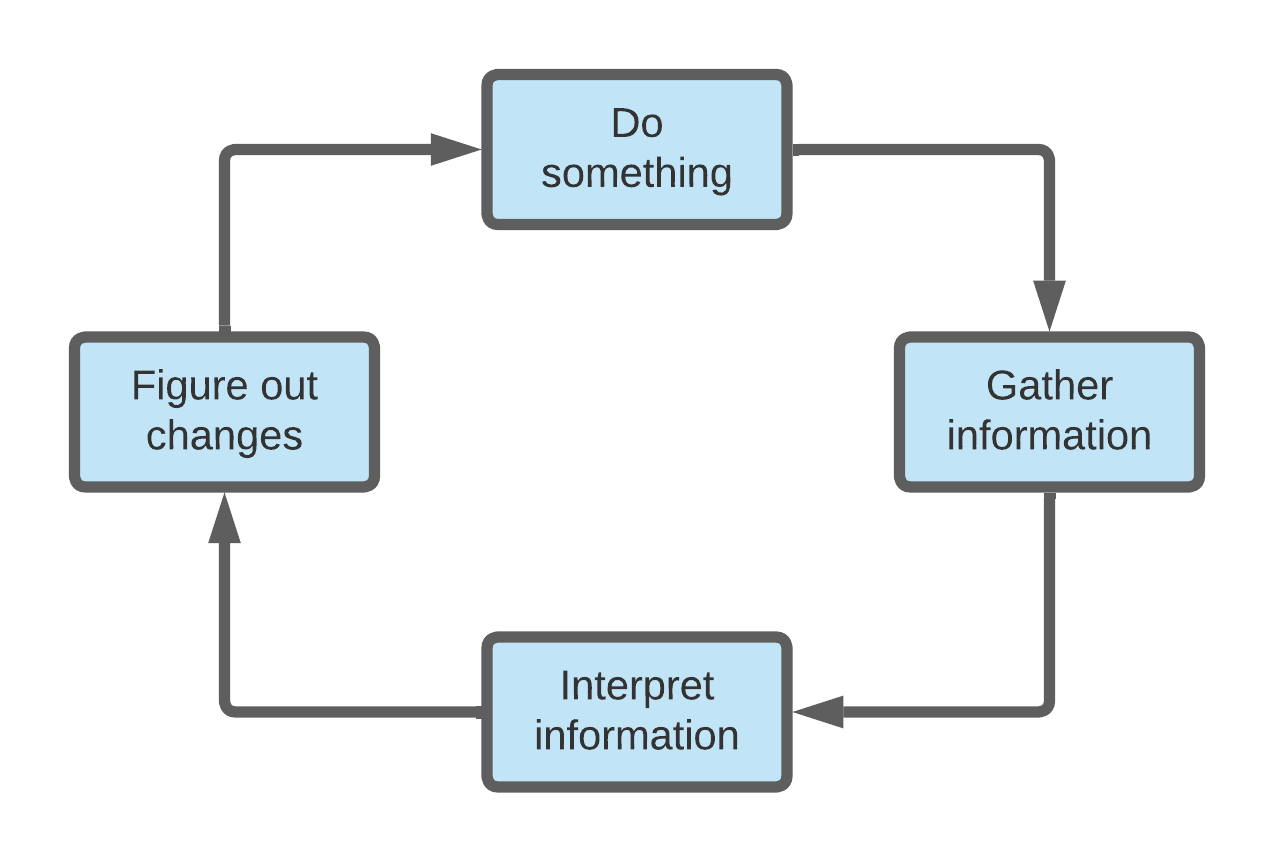

I have been thinking a lot lately about the particular nuts and bolts of what happens when a learner engages fully with a feedback loop:

If it’s true that everything important that we've ever learned, we learned by engaging with a feedback loop — then what exactly happens when we engage with a feedback loop to produce that learning? And as instructors, how do we build a learning environment for students where this kind of engagement is likely to happen?

In my last post I proposed that deliberate practice points the way toward what productive engagement with a feedback loop looks like. I even went so far to say that, regarding alternative grading, your grading system is only as good as its ability to elicit deliberate practice consistently from students. But it seems like it takes more than just a grading system to elicit this kind of practice. How does an instructor motivate students to engage in the kind of effortful, difficult, and frankly boring behaviors that constitute deliberate practice?

Whether this kind of motivation is possible and what it might look like is the subject of a research paper that I recently stumbled across while I was digging into the literature on deliberate practice. In today's post, I want to summarize this article and give some thoughts about how its findings tie into the Four Pillars framework for alternative grading.

The study

The paper I’m reviewing is:

Eskreis-Winkler, Lauren, Elizabeth P. Shulman, Victoria Young, Eli Tsukayama, Steven M. Brunwasser, and Angela L. Duckworth. “Using Wise Interventions to Motivate Deliberate Practice.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 111, no. 5 (2016): 728–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000074 .

There is a PDF linked to the journal articles page for this paper, and it appears that it's open access, so you can read it for yourself. (And yes, the “Angela Duckworth” in the author list is the same Angela Duckworth who popularized the notion of “grit”.)

It's well known from psychological literature that interventions (in the form of brief instructional modules and activities) can improve certain kinds of effortful behavior. But it’s not clear that deliberate practice, being a more stringent and, well, effortful form of effortful behavior, obeys the same set of rules for motivation as other forms. The authors intended this study to see whether “wise interventions” could motivate non-experts to engage in deliberate practice and improve their achievement.

A “wise” intervention is one that is theory-driven and designed to change a specific psychological process. Wise interventions often tend to be “durable” because they target key psychological processes that can perpetuate themselves over time through “recursive cycles”. Many interventions aimed at developing a growth mindset (a different sort of target than deliberate practice) are “wise” in this sense because they reframe subjects’ basic rules of engagement with their behaviors — by shifting to a growth mindset generally, a multitude of more localized and specific behaviors can change, “recursively”.

The intervention designed by the authors was grounded in Expectancy Value Theory, a theory of motivation that posits that a person's willingness to engage in a task is determined by two main factors: their expectancy of success and the value they place on the task. The authors’ intervention, again designed to motivate deliberate practice, aimed to increase students' expectancy for success by teaching them that deliberate practice, not just innate talent, is "incredibly important to improvement and success"; and address the negative "costs" of practice by encouraging students to reframe frustration and confusion as positive signs that they are challenging themselves and improving.

The methods

The authors developed a new tool, the Deliberate Practice Task, to measure how much time students chose to focus on challenging math problems, as opposed to distracting websites. The subjects were given a series of challenging math problems designed to give immediate feedback and level up to a harder problem if the current one was done correctly, in a 45-minute session. These were administered online, and subjects were allowed to access various websites during the testing period — in fact they were encouraged to use those sites to take breaks. Deliberate practice was operationally defined simply as the amount of time students chose to spend on-task versus off-task.

In the first iteration of the study, 209 fifth- and sixth-grade students were randomly assigned to a treatment group where they received a wise intervention, or to a control group that taught standard study skills.

In the intervention group, subjects received text and video content where they learned the basic ideas of deliberate practice: Focus on weakness, get feedback, concentrate fully when working, and repeat until mastery. The instructional materials were interspersed with activities and a letter-writing exercise where each subject wrote a letter to another student summarizing the value of what they were learning. The module taught that “talent and effort both contribute to success, but that the relative importance of effort, especially effort invested in deliberate practice, is often underestimated.” This addresses the “expectancy” part of Expectancy Value Theory. To address the “value” part, the module encouraged students to reframe frustration and confusion as positive signs that they are engaging in effective practice1.

Student performance was defined as the total number of points earned on the math problems. There were up to 100 points in each of 19 multiplication and division topic areas for a maximum of 1900 points. At the end of the intervention, students were also asked to rate how interesting and engaging they found the module. Students rated those two adjectives using a 100-point slider scale, which were then averaged into a single number.

This basic form of the study was repeated, once using college students, and then with an expanded 50 minute long intervention for middle school students in the sixth and seventh grades with one month and four month follow up studies to measure whether the intervention was “sticky”.

The results

In all iterations of the study (middle school and college students, short term and long term) the researchers found that the deliberate practice intervention significantly improved the achievement of lower-performing students. For college students specifically, the intervention had a significant effect on end-of-semester grades, principally driven by improvements among the lower-achieving students.

Higher performing students actually experienced a significant negative effect by the intervention. The authors theorized that it was because they were being told to focus on their weaknesses, and did so, preferring the more challenging problems to the easier ones.

In the iterations of the study that involved follow-up periods, the students in the treatment condition reported stronger deliberate practice beliefs than those in the control condition that persisted up to one month later. Students in the treatment condition also reported higher tolerance for frustration than those in the control group after the first and second follow-up. They also earned higher fourth quarter GPAs than those in the control group. Again, driven mostly by improvements among the lower achieving students.

What this means for the rest of us

Readers of this blog know that one of the Four Pillars of alternative grading is Helpful Feedback. I've often framed helpful feedback as feedback that invites students to keep participating in the feedback loop. After reading this paper, I feel like there’s more that I can do to make my feedback truly “helpful”.

For example, if a student turns in a piece of work and it doesn't meet my clearly defined standards for successful work, and I simply tell the student, “Don't worry, here’s what needs additional work, just try it again”, then while that's somewhat helpful, I'm not equipping the student with the right frame of mind and the right tools to make the next few iterations of the feedback loop productive.

Instead, specific feedback for students might include specific instructions or comments, aimed at expectancies or values about practice, or practical tips for practice, or both. For example, if I am giving feedback on student work on a mathematical proof that has some significant flaws in the argument, I will certainly point out those flaws and explain why they are flaws, and then encourage the student to rewrite and resubmit. But I could also help the student practice by giving exercises to the student that target the specific points that need revision (for example, specific computations of increasing difficulty level that target understanding of the abstract concept involved in the proof), comments aimed at managing expectations (“This proof will be hard to understand and write without doing specific exercises first”), or comments on why the practice is valuable (“Once you put in some time on these specific exercises, you’ll feel much more confident in your writing”).

I also might note that feedback doesn't have to be just individual. Feedback can also be given to a larger group, or even on a full class basis, like the intervention that these authors did. I think it would be a good use of time, perhaps in the first week of class while I'm discussing the grading system, to conduct an intervention with my students, just like these researchers did with their subjects. This would set the stage for the entire semester to provide a common language about deliberate practice and a common set of beliefs and tools for making it happen, both in the class meetings and in students' individual work at home.

Speaking of the Four Pillars, it's tempting to believe that having reattempts without penalty in your grading system will, all on its own, motivate deliberate practice among students. I think all of us who use alternative grading systems know this is not the case. Reattempts without penalty is a necessary but not sufficient condition to elicit deliberate practice from our students: There’s not much value in practicing if you don’t get reattempts, but just because reattempts are possible doesn’t mean students will magically discover how best to practice in order to have a successful reattempt. That takes something extra, and this paper's intervention might point the way.

Questions I still have

Like any scientific study, this one has some constraints that are fair to address and lead to interesting questions that might motivate future research:

The study was limited to students working on math problems, which were procedural and rote. What happens when you have a classroom situation where things are not so cut and dry, where “practice” is somewhat more ill-defined — for example in a course based on discussion and writing?

What about those high-achieving students whose outcomes actually got worse as a result of the intervention? The authors of the study gave a theory for why this happened, but is there more to it? And how might an intervention aimed at deliberate practice be tuned to make these students’ performances even better?

College students only constituted a small portion of this entire study and part of their “performance” was measured using traditional grades and GPAs. Are there better, more growth-focused ways to determine if the intervention was working? (How might this study be replicated in an alternative grading setting?)

The study never actually observed students doing their practice. It only gave them an intervention with some general rules for deliberate practice and motivational ideas and then measured the results of their work. But could there be an observational study that takes a look at how students are actually engaging in the practice that they're being motivated to do? I’d especially like to know, again, about those high-achieving students — were they already engaging in sound deliberate practice behaviors before the intervention? And what changed for those students afterwards, that might explain their drop in performance?

The hope that this study gives us is that deliberate practice, though difficult and not particularly enjoyable, still obeys the same rules of motivation that any other form of effortful behavior obeys. It can be motivated, both on a small scale and a large scale, with younger students and with older students, with low achieving and with high achieving students, in such a way that core behavioral changes are real and persistent.

I tried to locate the actual intervention that was used, but unfortunately this was apparently only found in an “online supplement” to the article at the journal’s website when the article was published, and that supplement has since disappeared.

Thank you for sharing this. I think you're asking good questions at the end. Personally, I find myself skeptical about studies like this, and specifically about the way that they reframe the real work of learning in more measurable but less meaningful forms. "Deliberate practice was operationally defined simply as the amount of time students chose to spend on-task versus off-task." OK, but isn't deliberate practice more than a matter of which screen you're staring at? And doesn't a truly "wise intervention" entail more than infodumping a module of text and video content?

Part of my concern is the way that what is measurable becomes what is packageable becomes what is prescribeable, so that we end up with school systems adapting a Deliberate Practice Curriculum that's really just a reskinned form of rote learning, while the actually meaningful work of learning and teaching gets denatured away in the standardization process.