A growth-focused icebreaker

Two questions that can accomplish much in an alt-graded class

I hate icebreakers. I don’t use that word “hate” often or lightly. But here, it’s justified. The purpose of icebreakers is, supposedly, to get people involved in some activity to make them more relaxed when working together. But the idea of going through some contrived activity, with a group of people I don’t know, specifically to expose myself to them on a personal level, usually through some horrifyingly embarrassing action or fact I’m forced to share — does not in any way relax me. And most of the time, icebreakers accomplish nothing except a lot of eye rolling and spiked anxiety levels.

So I’m not a fan of icebreakers. Therefore, when I say that I’ve finally found an icebreaker activity that really works, and one that I can live with, it’s a big deal. I’d like to describe it to you today. I use it on the first day of every class, as well as in the talks and workshops I give. You can run this activity with students at any time of the semester and get good results. In fact, it benefits from being given repeatedly throughout the semester. And it reinforces all the ideas about learning and growth that we write about on this blog.

Here’s how it works.

Two questions

The activity is very simple: I ask students (or audiences, workshop participants, etc.) two questions:

What is something that you are good at doing?

How did you get good at the thing you are good at doing?

I like to give these one at a time as think-pair-share questions. I will display the first question on a slide (or just say it out loud), then give everyone a little time (30-90 seconds, this usually doesn’t take long) to think about their response. Then they are instructed to pair off and share responses with their partner. If they are in groups of four, I might have the pairs pair off and have a 4-way sharing session. Then we do a large-group share of the responses. (In a class, you might have each student in a pair introduce the other to the class, using the other person’s “thing they are good at doing” as an interesting fact.)

For the second question, I also do this as a think-pair-share, but people respond using a polling tool like PollEverywhere to make a word cloud of the responses. Having a visual representation of the responses with the most common ones being the largest is important for this question, for reasons you’ll see below.

This activity can take as little as 5 minutes, or you could build an entire hour-long class unpacking the results and telling stories about how people got good at various things. There are a lot of variations you might try. However it’s done, these two simple questions not only teach you some things about your students, they reveal a great deal to students about your class, particularly if you are using alternative grading.

What are you good at doing?

When I ask this question, the only instructions I give with it are that the “thing” you’re good at doing has to actually be something that takes nonzero effort to do — sleeping, watching TV, biological functions, etc. aren’t allowed. Only rarely do students respond with academic things, even if it’s in a high-level academic environment. They don’t say things like chemistry, studying, or taking tests. They say things like snowboarding, soccer, guitar, Super Smash Bros, and the like.

In fact, I just gave this activity to my students on the first day of class, using a word cloud tool, and here are the responses from one of the sections (the other had similarly varied responses):

On its own, this question does good work for students and for us: It reinforces the fact that every student is good at something and not only “something” but a thing that requires focused effort and pushing through discomfort. I find students need to be reminded sometimes that there are things in their lives that they care about so much that they put up with the process of getting good at them — maybe even came to enjoy that process.

As an instructor, this question reminds me that students are human beings with lives that have greater depth than I often realize. There’s so much hand-wringing about the so-called “disengagement crisis” in higher education, but insofar as that crisis is real, it’s of our own making. Students know perfectly well how to be engaged with something difficult. If they don’t engage with us or our classes, that can’t be completely the student’s fault.

How did you get good at it?

Here’s the word cloud from my class, for the second question:

Every time I give this activity — whether it’s with students or faculty or ordinary people — the top responses are always the same: Practice. Determination. Effort. Time. Failure. Consistency1. This word cloud could be from any class, keynote, or workshop that I’ve facilitated in the last several years since I’ve been doing this activity2.

When I debrief students on these responses, I point out that the main responses are always the same no matter the audience. I also point out that there are certain ideas that never show up in these responses: Lectures. Exams. Points. Grades. The traditional structures we set up in the name of learning are never the ones that real people link with real learning. Occasionally, someone will reply with Teacher; when I ask for clarification, “Teacher” always comes to mean something like “Coach”, as in I got good because I had a teacher who was really responsive and gave excellent feedback. It’s never, I got good because I had a teacher who gave great lectures.

What we learn from this exercise

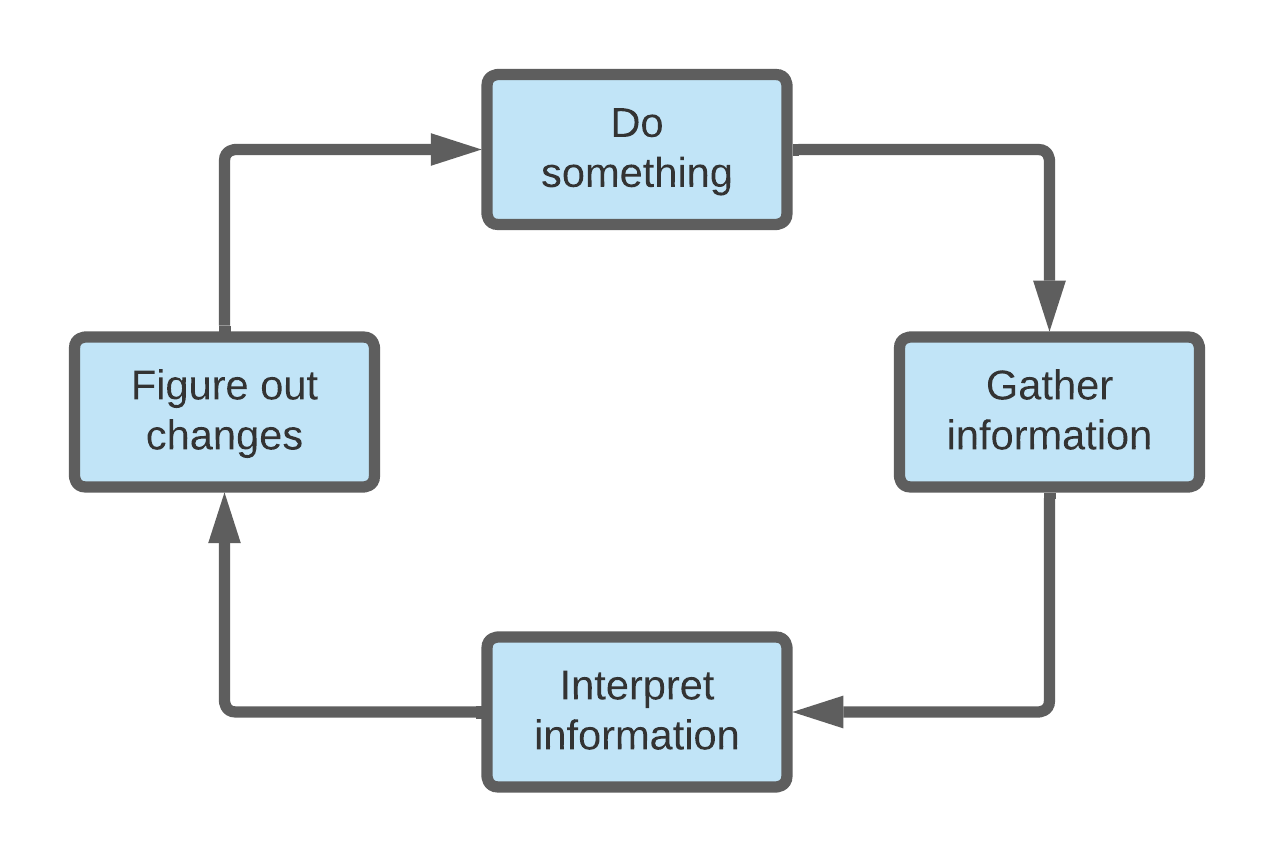

Students know perfectly well how to be engaged with difficult things, and they are crystal-clear on the process by which mastery of such things happens. They are not only clear on this process, they can point to concrete examples in their lives where this process produced many of the most important facets of their lives. That process, of course, is the feedback loop.

The feedback loop is the central organizing principle of all alternative grading systems and the roof of the Four Pillars model. The reason this is the case, is that — as students are very well aware, according to Question 2 — all significant human learning experiences happen through engagement with a feedback loop. And the biggest thing we learn through this exercise is that students have an intuitive grasp of this fact. It’s not something that requires extensive explanation or “buy-in”. It’s a fundamental part of students’ lives — and they know it3.

These two questions very economically get to the heart of the matter in a college class: We’re trying to get good at something hard; how does that happen? Well, we can ask in reply, how has it ever happened? Answer: Through engagement with a feedback loop. Therefore to the extent that feedback loops are driving the work of the class, we can expect meaningful learning to happen. And this goes both ways: If there are no feedback loops to engage with, we can’t expect real learning to happen except maybe by accident.

If you are using alternative grading, the responses to these questions and the lessons we learn from them give you all the tools you need to address pushback, concern, doubt, or misunderstanding about the grading system. Just pause and ask: What are you good at doing, and how did you get that way?

Students, and all other humans, have a deep store of failure narratives that also have happy endings. It’s part of what makes every person uniquely interesting and invested with dignity. Once you, as an instructor, can tap into it and hold it up as a mirror to your students, I’ve found there’s very little convincing you must do get students on board with your grading system, because your grading system is the most natural thing in the world now. It’s just real life, which doesn’t flinch from the hard work of growth.

And that’s why this is an icebreaker that I can live with.

The students and I decided “consityis” is supposed to be “consistency”; some people were responding on smartphones.

However, this is the first time I’ve seen “Covid” or “lockdown” show up in the responses, which I found very interesting. When I asked for context, what people meant was that during the Covid lockdowns, people had the time and availability to really focus on the activity they’re (now) good at doing, which allowed them to get good at it. There are a lot of lessons we can learn here about minimizing course structures, keeping things simple, and providing students with time and space to work and to breathe. I explored this a little in my post about the 12-week plan for course building.

On the other hand, getting students to realize that they know it, and therefore that feedback loops and not points plus one-and-done assessments are the most appropriate basis for a grading system, can require sustained effort, to put it mildly.

Wow! I have finished four classes and built a good classroom climate. The registration window closes today so next class will be the moment we move into permanent teams and this activity will be a WONDERFUL way to begin that experience. Great timing, thanks :) You show up as a cited reference in so many places in my course!

Thanks so much for sharing this idea. I used it today in my Intro Stats courses (day 2) and then asked them to take a survey on growth vs. fixed mindset. When we moved to talk about the survey, I could immediately point to some activity where each of them exhibited a growth mindset in their lives already... and then encourage them to be open to a growth mindset in stats.