Helping new TAs find value in required training

How alternative grading increased satisfaction in a large online, asynchronous, pass/fail course

Today, we bring you a guest post by Daphna Atias and Robin Pokorski, who are both educational developers at the George Washington University in Washington D.C.

Introduction

Each semester, we teach an online, asynchronous, one-credit, credit/no-credit course to new graduate student teaching assistants (TAs) at the George Washington University (GW), a mid-sized R1 in Washington, DC. The course, Foundational Pedagogy for Graduate Assistants, is required of all first-semester TAs, and it enrolls approximately 330 students in the fall and 100 in the spring. We think there’s tremendous value in teaching graduate students how to teach effectively (the two coauthors, after all, work at GW’s Center for Teaching Excellence). But for students, the course often presents a headache. It suffers from a reputation as a compliance-based hurdle that students must pass in order to continue to serve as a TA (and therefore earn their salary and tuition in this notoriously expensive city). Students have perceived it as disengaging and disconnected from their actual TA duties and the rest of their graduate studies.

In Fall 2022, we implemented an alternative grading system based on a modified EMRN rubric along with flexible deadlines and the possibility of reattempts without penalty. Our goal was to try to improve students’ perceptions of the course and thereby increase their buy-in and satisfaction with an important component of their training as graduate students. The flexible deadline policy was inspired by the first full pandemic semester, when we fielded over a thousand individual requests for deadline extensions. Although we liberally granted these extensions, the volume of email was untenable. But the rest of our impetus grew out of a desire to help students find meaning in the course and, we hope, in their role as TAs and as teachers in many forms throughout their lives and careers.

The course

Our course design decisions were motivated by the number of students enrolled in the course each semester, the staffing support we have from two TAs for grading and replying to student email, and the characteristics of enrolled students. TAs at GW range from masters’ students serving as graders and maybe holding office hours to PhD students who lead discussions and labs, and all permutations in between. Students come from a wide range of GW’s schools and departments. Students also tell us that they have different perspectives on the value of serving as a TA: some hope to pursue future teaching opportunities, while others are serving as a grader for a semester or two to earn a paycheck. We have built options into the course wherever possible to allow students to complete a reading or assignment that aligns more closely with their circumstances.

Foundational Pedagogy is divided into six two-week modules on key teaching topics:

Module 1: Getting off to a successful start

Module 2: Planning a discussion section, lab, or review session

Module 3: Facilitating a lab, discussion section, or review session

Module 4: Grading and providing feedback on student work

Module 5: Reflecting and improving

Module 6: Teaching inclusively

The six modules are created in Blackboard, our learning management system. Each includes a mix of course text (which we wrote and tailored to our students) and outside readings and videos. Because the course is asynchronous, students’ interaction with it is primarily self-guided, prompted by regular announcements that help them track course milestones.

Although we designed each module to take two weeks and have tried to mirror the structure of a “typical” semester as closely as possible (e.g., Module 4’s focus on grading and feedback occurs right around midterm time in each semester), we invite students to work ahead as they prefer because we know there is such a wide array of TA tasks and roles. Some students may want information on grading and providing feedback sooner than the traditional midterm season; some may want as much information as possible about lesson planning and facilitation and elect to complete the first three modules quickly.

Because there are six two-week modules, the course wraps up before the traditional end of the semester if students hew closely to the schedule. We intentionally designed the course this way so that our students finish the requirement before crunch time kicks in, both in their own courses and in their TA courses.

Most modules have assignments associated with them. These assignments are designed to be short, to provide practice on key pedagogical skills, and to allow some choice in response to students’ circumstances like field or primary TA role. The written assignments are short-response, homing students’ attention towards module learning objectives rather than assessing students’ ability to write a fluent essay. We also use points to enable students to track their progress towards receiving the passing grade they need to continue serving as a TA. 70 out of 100 points are required for students to receive credit for the course. Although we acknowledge that using points is a somewhat unusual choice in an alternative grading context, we’ve found that it allows us to effectively balance the benefits of alternative grading with the challenges posed by a very large, asynchronous course.

The assignments are:

Module 1: Policy quiz (10 points). Students review university policies relevant to their TA roles.

Module 2: Lesson plan (20 points) & discussion board (10 points). Students develop a plan for a discussion, lab, or review session of 50 minutes in length using a template and reflect on its strengths and weaknesses in supporting active learning. They also post about a teaching challenge and respond to their peers.

Module 3: Class observation (20 points). Students watch one of three short videos of a teacher presenting a lesson and analyze the lesson’s support for student learning.

Module 4: Feedback analysis (20 points). Students respond to sample feedback to students on an essay or lab, reflecting on the relationship between grades and feedback and how feedback supports student growth.

Module 5: Feedback plan (20 points). Students generate a plan for soliciting feedback on a specific aspect of their teaching.

Module 6: No new assignments. Students can use these two weeks to submit late work or revise and resubmit work.

Assessing student work

Whatever assessment system we developed needed to work for our small course team. Our two course TAs are each paid for 20 hours per week of work and do the majority of the grading. We kept several questions in mind while designing:

How can we reduce the administrative workload for ourselves and our TAs?

How can we reduce grading time and focus grading and feedback on key issues, rather than meaningless point distinctions in a credit/no-credit course?

How can we incorporate the flexibility we are willing to grant students into the structure of the course itself?

We found the answers to these questions in two mutually dependent structures: specifications grading and a due date system that incentivized but did not require students to complete assignments based on the two-week module schedule. Reattempts without penalty, aided by feedback from the course teaching team, are only permitted if work is submitted by the module due date, and so these reattempts function as an incentive to turn in work by the posted due date. Additionally, students are able to earn the full point value of the assignment (10 or 20 points) if they turn assignments in on time; the total points available are reduced (to 7 or 15) for assignments submitted after the due date. This flexibility earns credibility with students, who appreciate our recognition of the multiple demands on their time.

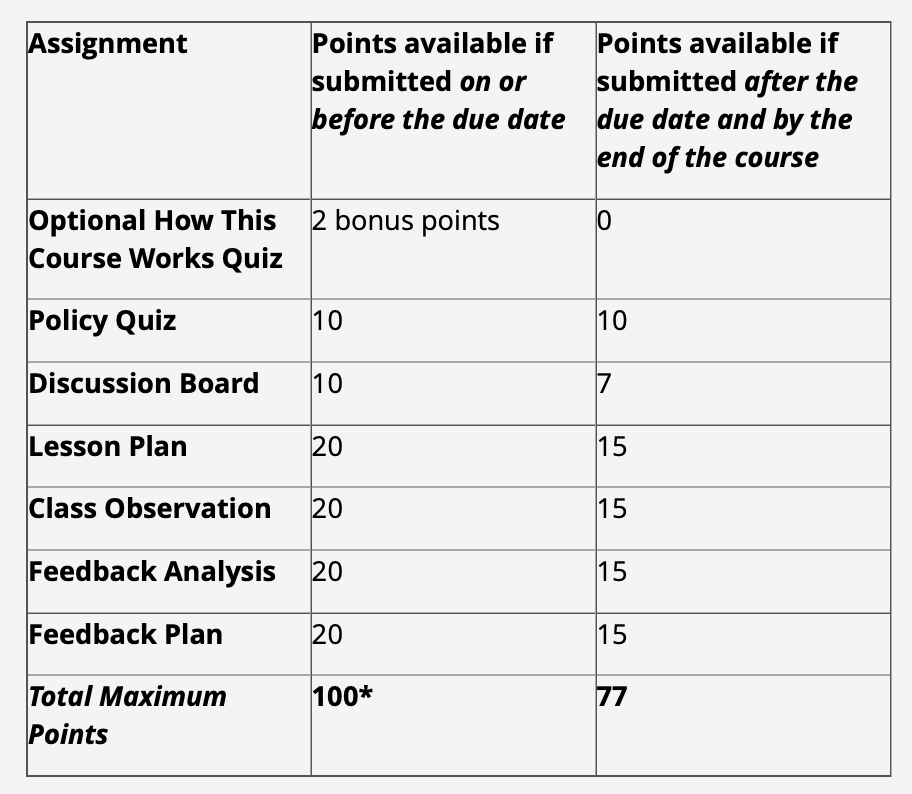

A chart on the syllabus highlights two potential, equally successful pathways through the course and allows students to navigate a range of choices in between:

We also explain to students that we assess each assignment according to a four-category rubric (successful, minor adjustments needed, progressing, and not assessable), where points are allocated based on the category where most of the assignment falls. Our basic assumption for all assignments is that all questions are answered and answers are clearly communicated in complete sentences. If not, the work is returned to students for revision and resubmission before we evaluate it.

Major assignments submitted on or before the posted due date receive point values as follows:

Successful: 20 of 20 points

Minor adjustments needed: 15 of 20 points

Progressing: 10 of 20 points

Not assessable/not submitted: 0 of 20 points

Assignments submitted after the posted due date but by the end of the course receive:

Successful: 15 of 15 points

Minor adjustments needed: 10 of 15 points

Progressing: 5 of 15 points

Not assessable/not submitted: 0 of 15 points

An example below shows how the specifications prompt students to remember and apply key elements of the module materials. It comes from the feedback analysis assignment, where students analyze samples of a graded English essay or lab report. This sample also allows us to explain how our system works. This hypothetical student is “successful” in one category of the rubric, at the “minor adjustments needed” level in three categories, and at the “progressing” level in the final category. Because the majority of the marks are in “minor adjustments needed,” this student would earn 15 points for an assignment submitted on time (and be able to revise it to earn the full 20 points), or 10 points for an assignment submitted late. Although we hope that the student in question would eventually be more successful when it came to evaluating the effectiveness of instructional choices, this decision streamlines decisions in the context of our large-enrollment, credit/no-credit course and effectively maps to the old traditionally graded system: we are not passing students who would not have passed previously.

The specifications also help us measure the extent to which students are engaging with the course readings and materials rather than pulling only from their experiences with teaching and learning.

Since the course is online and asynchronous, and since many students are new to alternative grading, we not only take pains to articulate how the grading system works but began last year to reinforce our explanation with a brief quiz. As an incentive to read the syllabus carefully and strive to understand the system, students can earn 2 bonus points towards the 70 needed to pass if they complete the 6-question quiz during the first two weeks of the course.

Conclusion

Our end-of-course feedback surveys reveal that though the challenges associated with other aspects of the course remain, our flexible alternative grading system has been a resounding success. In the year before we shifted to alternative grading, only 31% (33 out of 105) of students who responded to the survey felt that the course was a “tremendous help” or “helped a lot” with their TA roles. As we significantly overhauled other aspects of the course—reducing and refining course readings, adjusting course assignments to more closely mirror TA responsibilities, and jettisoning a largely dreaded video presentation—students’ satisfaction with the course increased: since Fall 2022, approximately two-thirds of the 536 survey respondents have rated the course as “tremendous help” or having “helped a lot” (the rate ranges between 47–72% depending on semester and represents a general upward trend). The positive responses to our assessment system significantly outrank perceptions of the course as a whole: 78% (418 of 536) of students said that the option to turn work in after the due date was a “tremendous help” or “helped a lot” in balancing this course with their other responsibilities. In their written comments, students no longer bemoan the regimentation of the course or point to a lack of empathy in the grading structure.

Students find our grading system helpful regardless of whether and how they use the flexibility afforded within the course structure—and their use varies. Depending on the semester, 43–67% of students turned in an assignment after the posted due date and 33–44% completed a module ahead of the due date. Many students read ahead in the course even if they did not submit an assignment early, affirming our suggestion that they navigate to the material that would be most useful to them at any given point in their teaching rather than sticking strictly to the reading and assignment schedule.

We know that a large, required course that serves an administrative function will never satisfy every student, but the changes we’ve made have resulted in much higher satisfaction. Although this course has many constraints, we—and, more importantly, our students—are generally happy with how it functions now. We do have a few areas where we continue to think about changes, however.

The first of these is the nature of the course itself. While we’ve spent a lot of time thinking about how the course and its grading structures can support students in developing as TAs, we don’t see them as the final word on how TA training should work at a large research university. We hope that, in the future, the course might be one of several available forms of support, functioning alongside other options such as intensive pre-semester workshops or departmental- or school-level programming, mentorship, and community-building.

The second is about our assignments. The changes that we implemented to make our course more manageable and to highlight what students should be learning and taking away from each module would benefit from rethinking in light of generative AI. Online, asynchronous courses are vulnerable to AI misuse, and ours, which students must pass to continue serving as TAs, seems even more vulnerable. Our alternative grading structure helps students avoid some of the deadline pressures that can prompt them to turn to AI, but likely isn’t enough on its own.

Course design is always a form of communication, and in a low-credit, credit/no-credit, asynchronous course where direct communication with students is limited, our flexible alternative grading approach functions as our most important and effective tool for flagging to students that we recognize the demands on their time and energy but believe in what we have to offer them. By reducing the pressure of deadlines and using specifications to flag key categories of teaching proficiency without haggling over details, the grading scheme allows us to focus our energy on the heart of the matter: supporting graduate students as people so we can support them as teachers.

Daphna Atias is an educational developer at the George Washington University, where she specializes in inclusive and equity-focused teaching practices. She is especially interested in the teaching of writing, alternative grading practices, and fostering students’ pedagogical awareness and agency as learners. A graduate of the University of Michigan, she has taught in numerous environments, including GW’s first-year experience and graduate teaching assistant training courses and secondary and undergraduate literature and composition courses.

Robin Pokorski is an educational developer at the George Washington University. She earned her PhD in medieval history from Northwestern University in 2022. Robin is particularly passionate about finding ways to foster student curiosity and engagement, alternative grading models, ways of providing feedback to students, and the training of graduate student instructors. She has taught a range of courses on medieval and early modern European history at Northwestern, Loyola University Chicago, and GW.

Excellent and enlightening. So helpful to "see behind the curtain". It's easy to see why satisfaction has increased so significantly. You've struck an effective balance with having the course actually mirror the concepts you encourage them to practice as TA's. I only hope their other education courses have done the same. As to your observation about AI, that was one of the first things that struck me as I read the Feedback - Module 4 example. Many of those elements could be done effectively using AI. I personally don't see that as a "challenge" but rather as an "opportunity". I hope there is room for discussion in the future about how the TAs can/should use AI and how to deal with and accommodate their students' use of AI.