Growth-based grading for future educators

How alternative methods can be used with outside standards

We’re pleased to welcome AmyK Conley as a guest author this week. AmyK Conley is a lecturer in the School of Education at Cal Poly Humboldt. Conley lives among the redwoods in Humboldt County, California with her partner and children. She earned her EdD in educational leadership from Fresno State University after teaching language arts in California high schools for 21 years. Her experience in the classroom has convinced her that education suffers from too much emphasis on grades, and not enough on learning and application.

Think about your favorite class from university. Maybe you learned a lot. Maybe your professor was an expert. But you remember the course, and what you learned in that course, because of how you felt in that course. The best courses make you feel like you are a valued insider, like you are going to master this field, like the learning goals are doable, like the instructor and fellow students respect you and your goals for the course, like there is a connection between the course and your personal sense of self – like your learning is more important than the grade.

Do you remember the grade in the class? I don’t remember what I received in feature writing from Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo years ago, but I remember that my professor expected, and gave, professionalism and civility and growth. I felt like a journalism insider after his courses. Heady stuff for a 19 year old.

My context

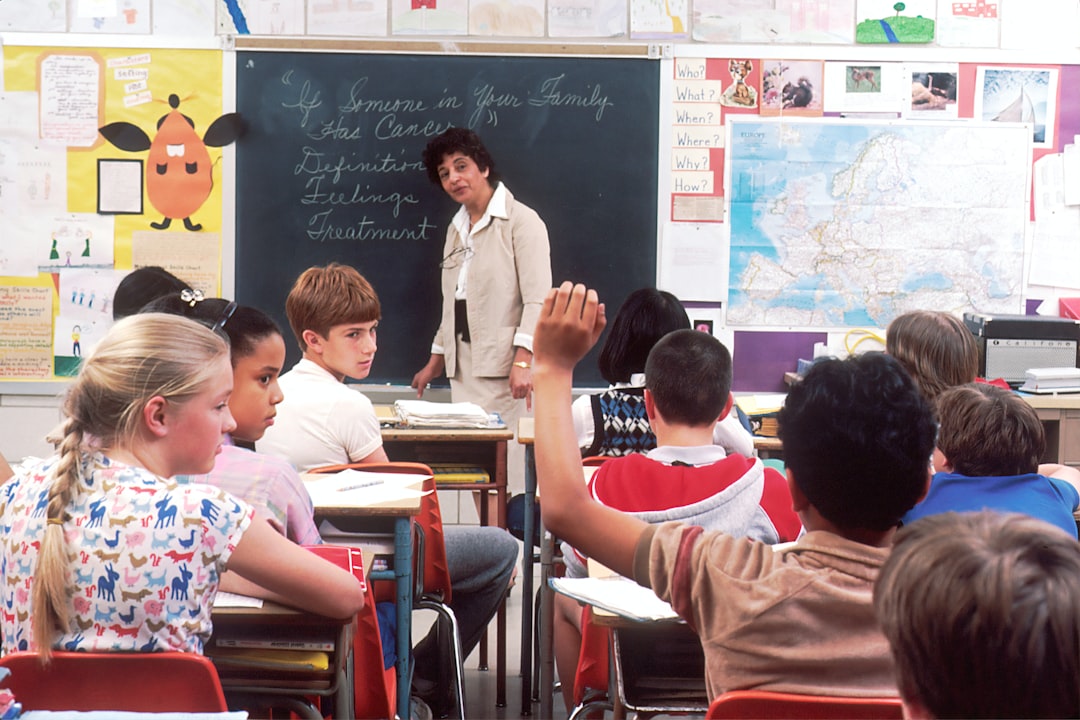

My life has twisted and turned since then, and I love working with future teachers on literacy for elementary and special education for my small, public university in northern California (student body about 12,000). Cal Poly Humboldt prides itself on welcoming diverse, first-generation university students from all over the state of California. I use growth-based grading in all of my literacy classes, but I first made the switch while teaching undergraduates in our innovative integrated bachelors and teaching credential program, Liberal Studies Elementary Education. In that program, students take education classes with a fieldwork component in elementary schools every semester of their undergraduate program and complete a year of solo student teaching as seniors. At the end of four years of university, they have earned their bachelors and a K-8 teaching credential. The 25 students in my course, Developmental Literacy, ranged from freshmen to juniors, but all also had an elementary fieldwork experience to practice what they learned about literacy.

You may have heard that reading levels are declining in elementary and there is a teacher shortage and declining enrollment in teacher programs across the country. Consequently, I am teaching crucial skills to people who need every encouragement to stay in the profession. How they feel about their coursework matters because they need to feel valued and supported to stay in this profession.

Growth-based grading against an outside standard

With that in mind, I have moved to growth-based grading against an outside standard: The “Knowledge, Skills and Abilities” (KSA) government white paper lists all of the literacy knowledge that a beginning teacher should have in California. For this course, we only use the foundational literacy standards, like phonemic awareness, phonics, grapheme and morpheme instruction, “Demonstrate awareness that the progression of phonological skills also includes rhyme recognition and repetition and creation of alliteration”, etc. Students learn other sections of the KSA in their other courses or in their fieldwork as student teachers before completing a Literacy Teacher Performance Assessment their final student teaching year.

I kept track of attendance and assignments completed and give extensive feedback, but students’ final grades were determined in conference with me on their growth in their confidence to teach the literacy Knowledge, Skills, Abilities (KSA) identified by the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC) for future teachers over the course of the semester. Attendance and tracking assignment completion helped students feel accountable and gave me talking points in conferences if students had not shown much growth against the KSA compared to their classmates.

Freshmen through juniors were enrolled in this course, so they had varying knowledge of pedagogy and literacy. Some were taking their first education class; some had taken multiple classes about elementary literacy already. Growth-based grading made that prior knowledge range more equitable.

Growth-based grading means that I am not an evaluator but an encourager. It means students see, listed on the first day of class, every concept that they will learn during the semester and are introduced to the grading scheme for this course. It means there is a document that all of us are accountable to eventually. They are held accountable as seniors when they complete their Teacher Performance Assessment on literacy, a portfolio of lesson plans, assessments, videos of them teaching, and their feedback on elementary student work that take place over the course of a week of teaching. I hold myself accountable to prepare them for the expectations listed. I hold them accountable by discussing their growth in conferences and pointing them to additional learning for after the course about concepts that they haven’t mastered yet.

Students self-assessed on the first day by marking every item with Canvas annotation on the 12-page KSA document with “I don’t know it yet,” “I know it but don’t yet know how to teach it,” or “I know it and could teach it.” (If you use Canvas, try the digital annotation feature!) Mid-semester conferences and final conferences were discussions about topics that they still didn’t understand and discussions about the grade that they thought they deserved based upon their growth. I referred back to their first day digital annotation of the KSA to discuss growth during the later conferences. We also talked about career goals and next steps for them.

Student feedback about growth-based grading

How did students feel about their growth and future in education?

Here’s a pull quote from one student evaluation:

Our professor would provide hands-on learning materials to enforce the readings and vocabulary from class. She made it very easy to be engaged and want to come to class to learn. She was always available for help when needed and always provided the most detailed feedback.

Students in conferences said that they learned more than they thought possible, partially because they were not worried about their grades, and were encouraged to stay in the profession. Some took reading tutoring or aide positions for summer school intervention programs! Some asked about supplemental reading authorizations after they earn their preliminary credentials. A supplemental reading authorization is earned in a one-year program after teachers have been teaching for at least five years and prepares teachers to be a reading interventionist that works with struggling readers all day, instead of a classroom teacher.

How did students feel about the unfamiliar grading system? Many reported feeling intimidated the first day by the length of the 12-page KSA, but also relieved that they could focus on learning and not stress about grades.

Final analysis of growth-based grading

For the mid-semester and final conferences, students had to review their growth on the KSA before their 10-minute meeting time with me and prepare questions for concepts they still didn’t understand.

Before making the change to growth-based grading, I was nervous that students who didn’t understand how to help children read would argue that any growth meant that they deserved an A. That didn’t happen. During midterm and final conferences, students were consistently impressed with how much they learned of that imposing, 12-page KSA. They also argued for a lower grade than I think they deserved and were excited to teach children to read, learn more about literacy, and stay in education.

The conversations I had with students in their mid-term and final conferences often sounded like this:

Me: How do you feel about your growth on the KSA, considering that things in your life limited your attendance and ability to complete assignments?

Student: I learned so much, but there is so much more I would like to learn and that I couldn’t get to because of [their important life event]. Honestly, I think my growth merits a D.

Me: That’s unfortunate because I know that your growth deserves a C, and I don’t think you can talk me out of it. There are only two concepts that you need to review and practice with students. Here are links to learn more about those concepts. Do you have a way to practice these with students? Will you be working in schools this summer?

Approximately 20% of students at mid-semester and 5% at the final conference requested a reteaching of at least one concept. It was helpful to the students for me to have video and resource links ready for conferences. There was no penalty for admitting they needed help, so students sought out additional resources to further learn the material.

Some students didn’t complete all of the assignments. Conferences were a time to ask, “This assignment was designed to assess your understanding of these concepts. Can you show me that you are ready to teach those concepts in a different way than the assignment asked you to teach them?” A few students were able to point to their jobs or fieldwork working with children, using the learning from the class, to replace assignments that dealt with the same concept. As a bonus, I got to see the amazing materials they were putting together for their work with children, based upon what we practiced in class!

Keeping the focus on nurturing future educators and helping them be ready to teach literacy requires a different point of view in grading – on growth, not points.