Grading for growth on a short time frame

Making alternative grading work when you don't have a semester

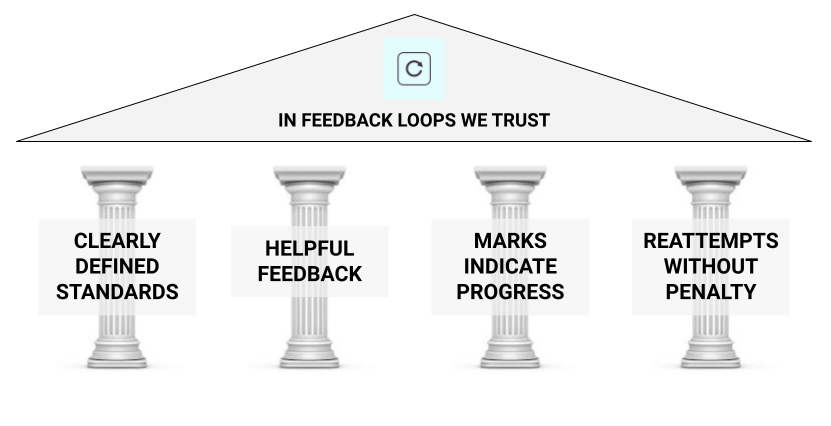

Learning takes time. It’s why, in alternative grading systems, we put feedback loops at the center of everything.

Time is the secret ingredient in this loop: Not only does it take time to go through the loop, the ability to take one’s time when iterating through it gives the learner the space to think about their work and themselves.

But what happens if you or your students don’t have as much time as you want? I encountered this question recently in a talk I gave to faculty at Northwestern University, whose academic calendar is on the quarter system — where the terms are 10 weeks long, compared to the typical 15 weeks of a semester. Specifically, someone asked:

A significant hurdle for students at Northwestern is catching up when they fall behind. Because we are on the quarter system, students must achieve mastery in a truncated time frame. How can we reshape grading policies and focus on student growth with the understanding that some students may not meet the desired learning objectives within the narrow time frame of the course?

Time scales shorter than 15 weeks are more common than one might think: According to this list there are 49 universities in the US using the quarter system, including Northwestern, Dartmouth, Stanford and seven of the University of California campuses. In addition, enrollment in summer-term classes is growing, and many such classes operate on 12-, 10-, 6-, or even 4-week schedules. I’ve had experience using alternative grading in those short-term classes including a 6-week version of the discrete structures course that I’m currently teaching in a 15-week semester, with roughly the same grading setup, and I remember asking myself this same question.

The good news is that doing alternative grading in a less-than-15-week time frame is completely possible. But it requires careful setup and management, and both you and your students need to be clear on what you’ve signed up for.

Setting expectations

It’s important to realize first that the problem our grading systems are trying to solve — which I’d argue is how to create a class culture predicated on engagement with feedback loops and where it’s safe to make mistakes — isn’t fundamentally different for a 10-week or shorter course than it is for a 15-week course. That is, just because the term is 10 weeks long instead of 15 doesn’t mean that the learning process is different, or even necessarily harder for students. Every learner still has to engage with a feedback loop on tasks whose completion provide sufficient evidence of learning.

Notice I don’t say “…whose completion proves the student has achieved mastery”, to borrow the language of the original question. One of the reasons that we moved away from the phrase “mastery grading” to describe alternative methods is that mastery of a subject is not typically a realistic goal within a 15-week semester, possibly even within a four-year undergraduate program, and to say nothing of a 4-week summer course. The best we can typically hope for in our courses, is that students will embrace feedback loops and show concrete evidence of learning, both of which make a solid foundation for a lifelong future road toward real mastery.

I think this is a helpful place to start, because once we get free of the notion that students should master the content of the course, the time pressure of a 10-week or shorter course eases up. Sure, there may be some content with which students should be very fluent, and we need to be clear about what that content is (see below). Expertise takes a lifetime, but evidence of strong learning is doable even on a very short scale, even when starting from close to zero in the subject. It happens all the time; it’s probably happened to you a few times.

What not to do

Before I give some thoughts on how to handle short time frames, here are two things you shouldn’t do.

First: You shouldn’t lower your academic standards. For example, if you teach with standards-based grading and require two demonstrations of skill on each standard in the 15-week version of your course, don’t lower that to one demonstration of skill on each standard in the 6-week version. This is, literally, a double standard that holds lower expectations for 6-week students than it does for the 15-week students, and that’s not fair. In other words, strive to hold the same or at least equivalent standards for your course that are independent of the term length.

I say “or at least equivalent” because in some cases it’s impossible to keep them the same. For example, if you require a research project in a 15-week course that takes 8-10 weeks to complete from start to finish, it won’t work in a 6-week version of the course. But rather than simply drop it from the syllabus, replace it with something that accomplishes the same learning objectives, such as 2-3 smaller mini-projects that are each 1/2 to 1/3 the amount of labor.

In the example above where two demonstrations of skill were needed for each standard, it might be reasonable to reconsider that requirement in all situations including the 15-week one. I’ll come back to that idea in a minute.

Second: You shouldn’t give up and go back to traditional methods. Traditional methods — using points and percentages and one-and-done assessments — do not solve the problem of creating a growth-focused class environment. They also don’t solve the problem from the original question of how to support students on a short time scale. They just take a bad idea and make it faster.

Making it work

When I taught a 6-week version of my discrete structures course, I opened the first day of class by telling students: I sure hope you all know what you’ve signed up to do. It’s a full 15-week course crammed into less than half the time. It’s not that we were going double-speed in class, but there was far less time in between classes to process information. I’m the kind of person who needs time for ideas to marinate before I understand them, and I would have been roadkill in that class! But many of my students thrived in it and actually preferred the 6-week format, because (they said) it made them focus. When you have literally no time to waste, you can’t procrastinate and you can’t let yourself get distracted.

That’s why I say that on a shortened time scale, the process of engaging with a feedback loop and learning from it isn’t really that different than normal, or even necessarily any harder for students. It just requires more focus. It’s not any harder to learn calculus, for example, in a 6-week class than it is in a 15-week class; you just have to minimize the number of things you are doing in addition to learning calculus so you can focus 2.5 times as hard.

The key to making alternative grading work in that situation, then, is making it as easy as possible to focus on the tasks at hand. So how do we do that?

Let’s go back to The Four Pillars first.

The Four Pillars outline some concrete steps to take, to help students gain the focus they need to learn well in a shortened term:

Make sure your content standards are exceptionally clear. The first pillars reminds us that clearly defined standards are always important. But the shorter the time scale gets, the less tolerance there is for unclarity or extraneous cognitive load. For example, the learning targets or objectives should be clearly written, using concrete action verbs and simple language. But not only this, the standards for what constitutes a successful demonstration of skill on each objective should be made clear as well. This document that we used in my 6-week discrete structures course, for example, lays out exactly what’s required for successful work on each kind of course assignment.

Make sure your feedback is simple and clear, not just “helpful”. Feedback that’s helpful is informative and encouraging. But the shorter the time scale gets, the lower the signal-to-noise ratio needs to be so that students can get into your feedback, learn from it, and get back to the feedback loop with a minimum of fuss or interpretation. Keep feedback short and to the point, as well as informative and encouraging. Research on feedback and academic performance suggests that just two sentences might be enough: One sentence to spell out what the student did well, and one sentence to summarize what to improve. You may find you need to edit what you write down before giving it to students.

Consider giving multiple pathways to reattempts, including some that are asynchronous. Reattempts without penalty are the heart of the feedback loop. But providing just one way to do reattempts, especially if it requires class time, might put students in a bind (for example if they have to miss a class, which is a major problem in 6-week and shorter classes). In my 6-week class, students took in-class quizzes on learning objectives; but they also had the option to assess these objectives orally through a Zoom appointment, or by making a video of themselves working a quiz problem and posting it to a class Flipgrid. This alleviated a lot of the time pressure on students to pass these assessments, and it wasn’t that much more work for me to grade them. This section of the course syllabus has the full run-down.

And there are two important rules to follow that aren’t from the Four Pillars but which tie into them.

First: Simplify your course as much as humanly possible. As with clear standards, the shorter the time scale of the course gets, the less tolerance there is for extraneous load. Do you want to use five different kinds of assessment in your class? Try to get it down to three. Are you planning to require three demonstrations of skill to achieve “mastery” on a learning objective? Consider making it two. Are you expecting students to read five books? Think about dropping your least favorite of those five. To help students focus, in other words, strip the course down to the bare minimum needed to make it a viable platform for demonstrating strong learning outcomes in the subject and a welcoming, growth-focused environment.

And as mentioned above, do this for all instances of the class, not just the short ones. Do the simplification to make the short-term courses work better; then import the simplification into the 15-week term versions.

Second: Make it a priority to ensure each student is 100% clear on how your grade system works. Again, reduce all extraneous cognitive load to zero or close to it. You might for example spend the first or second day of class just practicing how to assign course grades. You might give daily short, ungraded formative quizzes over the syllabus to give students some contact with it and surface any trouble spots. But whatever the method, make sure that if students are struggling, it’s with the content — not with the grading system. They don’t have time for both struggles!

So as long as we’re clear on the challenges of a shorter-than-usual academic term, and as long as we’re willing to help students focus their energies on engaging with the feedback loop and producing quality evidence of learning, alternative methods can do all the positive work that they do for a 15-week or longer academic setting. If you teach or have taught in a shorter academic term and have specific tips or methods that have worked for you, please share in the comments!

A timely post, thanks. I am deciding whether to teach a summer class for the first time.